A quick review of one of the most interesting books I’ve read in awhile.

A quick review of one of the most interesting books I’ve read in awhile.

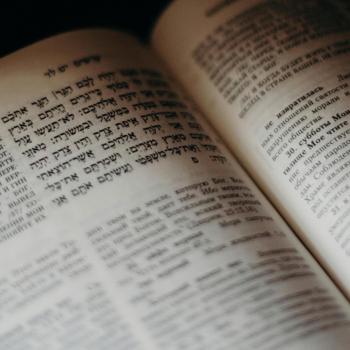

In his book Paul among the Postliberals, Douglas Harink challenges the overly simplistic understanding of Paul’s writings which holds that he was chiefly concerned with justification as matter of personal salvation through faith in Christ. He critiques the traditional translation issues with the rendering of Paul’s words as “faith in Jesus Christ” opting for “the faith of Jesus Christ” for grammatical reasons, but more importantly because the former is too anthropocentric.[1] According to Harink, who follows many post-liberal theologians here, this familiar reading is more entrenched in Liberal Protestant theology than it is in the text. He notes that even in Paul’s telling of his own conversion in Galatians, he does not characterize himself as working to win God’s approval. He doesn’t show himself racked with guilt or fruitlessly attempting to be holy, then learning that his works fell impossibly short so he stopped his striving and simply had faith instead. This is not the situation Paul paints for followers of Jesus.

Harink takes issue with the idea that Justification by faith is the core of Paul’s conversion and proclamation to the nations. He also disputes that the faith/works dichotomy is really pointing to a personal passive receptivity of grace, as well as whether Jewish Torah observance/non-observance is a primary polemic for Paul.[2] He emphasizes that having the faith of Jesus Christ is modeled by Jesus who died faithfully for all humanity while looking faithfully to God. The story of the Gospel which Paul represents is patently Christocentric – which is to say it really does not reference human disposition of faith.[3] God’s response to our “faith” is not unlike God’s response to attempts to keep the law. Faith comes at God’s initiative, for God’s action “is what elicits faith from us.”[4] Harink likens justification more to “rectification” in Paul, and this is a much more robust term than simply canceling the debt of sin. Barth, Harink says, viewed justification more as “justification by the faithfulness of Christ.”[5] This seems helpful.

Harink looks to Barth, Yoder and Hauerwas for support. In Barth, the faithfulness of Jesus had salvific or justifying significance. Thus Christian existence is primarily participation in Christ and the Holy Spirit.[6] For Yoder justification is both cosmic and social, fixed on God’s “right making action in Jesus Christ” and primarily concerned with “matters of social/ethnic division and enmity between Jew and Gentile.”[7] Thus faith is really an affirmation about Jesus as Messiah, not just an inner trust – it is active in both realms. For Hauerwas justification and faith are both “immediately marked by a specific and visible way of being and living in the world.”[8]

Harink seeks to characterize Hauerwas as a sort of post-liberal radical apocalyptic and likens him to the Paul of Galatians. In making this comparison, Harink seeks to elucidate the apocalyptic nature of Paul’s writings and to rightly characterize all which that entails. Apocalyptic is positioned as theology “without reserve,”[9] which is particularly interested in God’s action and conflict with and over the powers of the earth. Apocalyptic refuses to allow the culture to define faith, but insists that Christ is not the apex event of history, but rather Christ is the event which makes history intelligible in the first place. Thus there is really no need to make the gospel intelligible in culture, but only the need to unapologetically allow Jesus Christ to define the terms of the entire conversation about the world, humanity, God, etc.[10]

Harink says that in critiquing American Liberal Democracy, Hauerwas is really seeking to reveal the fact that loyalty to any nation-state requires a relinquishing of and sort of allegiance which could be described as “faithful” in a Pauline sense. Not that one cannot be American and Christian, but the faith of Christ will dictate the terms upon which one could (or in some cases could not) consider oneself American (or anything else for that matter). Part of why this important for Hauerwas is that the sectarian impulse must be resisted. As a quick interjection at this point, I found this argument particularly helpful because in my own ministry context it’s really difficult to find traction on issues of nationalism in anyway which does not elicit strong resistance. But, I think it is an important issue and something we should be confronting our congregations on as much as we would with, say, consumerism, racism, materialism or any other “ism.”

Harink takes the long way around in engaging Yoder’s work. The chapter expands upon The Politics of Jesus and Body Politics to try to engage the question, “Does Paul have a politics, and if so what is its shape?”[11] Not surprisingly, Harink says, “Yoder combined the key elements of each of these strands of current Pauline scholarship into a compelling rendition of the coherent center of Paul’s theology as a political theology focused on the cross of Jesus Christ.”[12] The main contours as Harink categorizes them are in five categories. Christ. Jesus as the crucified and risen son is the Lord and is normative for all life including politics. Cross. The Cross stands as the focal point of history as the non violent stance of Christ against the powers of violence and rebellion, which includes politics. Powers. Rebellious powers in whatever form they may take must be resisted in the same way Christ did – in readiness to suffer rather than in violent revolt. Ekklēsia. The victory of the cross creates a new human community which is called to embody the reality of that victory over the powers. Witness. The Ekklēsia does not become a sect, nor does it simply comply to the powers which rail against God, but the witness of the church is to live in the way of Jesus Christ (non-violent protest) in the midst of cultures which oppose God.

Harink is quite critical of what he calls the supersessionism of N.T. Wright in Chapter Four. He wants to emphasize God’s open ended election of Israel. I’m critical of this take on right because it seems like he misses the them so prevalent in works like The Challenge of Jesus which insist that we can see the work of Christ, at least in part, as ushering in the end of exile for Israel. This does not equate to ending Israel! I read Wright to say that Israel is not abolished but transformed and fulfilled. He seems to work more in themes of reconstituting the people of God in an Israel-inclusive way. Even the theme “return from exile” connotes continuing relationship. I’m not a scholar of Harink or Wright’s work, but this seems a mischaracterization of Wright, an author I have great appreciation for.

Harink’s major thesis seems to be that the ideas of justification that were purveyed by the Reformation are severely anemic if not outright misrepresentative of Paul. This seems to be a critique that we need to hear and I think Harink makes the case brilliantly. I’m appreciative of the breadth of the material covered and I really think there is a lot to work with here in terms of teaching and preaching in a ministry context. I can see this work used specifically in dialogue with the writers he engages. In other words, I’m not sure I’d use this book in a church bible study, however we might study Yoder’s The Politics of Jesus, in which case this book will be incredibly helpful as a leaders manual. It is such an incredibly daunting task to attempt to reframe Paul in light of the Postliberal theology, but I think it’s worth the effort. This task has to be undertaken very carefully and slowly, at least in my context but it must be done nonetheless. Though I may differ with Harink on a few points, I really think that this book will be of great help to me in ministry context. In fact I’m quite sure I’m not done with this book. Just the considering the simple idea of “faith in Jesus Christ” versus “faith of Jesus Christ” and the way that might affect one’s ecclesiology will keep me busy for awhile.

[1] Douglas Harink. Paul Among the Postliberals, Grand Rapids: Brazo, 2003. 28-30.

[2] Ibid., 40. Harink is particularly unenthralled with N.T. Wright and other purveyors of the New Perspective on Paul. I’m not sure that I share his critique.

[3] Ibid., 42.

[4] Ibid., 43.

[5] Ibid., 45.

[6] Ibid., 55.

[7] Ibid., 59.

[8] Ibid., 64.

[9] Ibid., 68.

[10] Ibid., 83.

[11] Ibid., 146.

[12] Ibid., 147.