Artists Resisting Authoritarian Regimes

There’s a reason authoritarians fear poets, musicians, and storytellers. Artistic expression constitutes a powerful form of resistance to authoritarian regimes. When governments ignore civil rights and erode freedoms, artists become dissidents by definition. Every act of free expression becomes a form of rebellion. “Totalitarian regimes fear poets more than soldiers,” Hannah Arendt wrote, “because soldiers can be defeated, but ideas cannot be killed.”

It’s possible that nothing could be more important to the future of America in this moment than grassroots, underground artistic expression. Artists can topple authoritarian regimes. It has happened before.

The Prague Spring

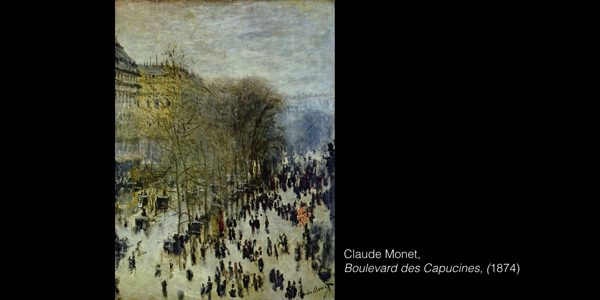

If you plopped down in Prague in the early 1960s, you’d see a bustling medieval marvel of a city, now made gray and heavily surveilled. Soviet censorship strangled free expression and creativity, while Secret Police monitored dissent. A thick cloud of authoritarian control stifled this once vibrant cultural center.

In 1968 a new president began reforming Stalinist policies. Posters for rock and roll shows lined the streets. Lectures and poetry readings sprang up in cafes and coffeehouses. Artists, filmmakers, poets, and musicians crept out from behind the Iron Curtain and ushered in The Prague Spring: a brief period of political reform and artistic freedom that lasted for seven months.

Then the Russians put an end to it. The Warsaw Pact Nations invaded, arresting dissident leaders, and halting reforms. They imposed martial law, reinstated censorship, and nearly overnight almost every artist in Prague was branded a dissident.

Plastic People of the Universe

That same year a local band called The Plastic People of the Universe played their legendary first gig. They came out dressed in long gowns that spelled out UFO. A wooden flying saucer hung from the ceiling, giant balloons of transparent plastic stretched floor to ceiling, as fires burned in giant ashtrays. It was the kind of 1960s trippy performance art Andy Warhol would have loved. Their music was wild and experimental and frankly, not very good. Their manager explained what was remarkable wasn’t the quality of the music, but the fact that they were playing at all.

Soon the regime required all musicians to have a license to perform in public. The Plastics submitted their lyrics and auditioned for the jury, but their request for a license was denied. So they got creative, promoting their gigs as art lectures. The lectures would last ten minutes, then they’d offer a “demonstration” on the topic, and jam for two hours. Eventually, the authoritarians shut this down.

Then they discovered unlicensed music was still allowed at weddings. Every wedding in the underground scene became an excuse for The Plastics to play. Members of the group got legally married, and one divorced couple remarried so The Plastics could be their wedding band. Eventually, the authoritarians halted this as well.

The Plastics started setting up gigs in barns and farm buildings outside Prague. They would share the location at the very last minute. Fans would flock to see the show, then try to disappear before the Secret Police showed up. Soon informants began infiltrating the underground music scene, and rural gigs became harder to pull off.

They went on like this for about five years, during which time a new member named Vratislav Brabenec joined the band. A former theology student and jazz musician, Brabanec began writing songs for their first album titled: Egon Bondy’s Happy Hearts Club Banned. Egon Bondy was the pen name of a banned Czech dissident poet who wasn’t allowed to publish. The Plastics set his words to music as a powerful act of resistance.

Non-Political Art Becomes Political.

The Plastic People of the Universe never set out to be political activists. They were just rock musicians. It was the politicians who made them political, by being offended by their music. They did poke fun at the foolishness of the authoritarian regime who tried in vain to silence the Czech young people. As the band’s popularity grew, The Plastics often wound up in jail alongside their own fans.

Soon other bands started popping up, and in 1976 they planned a big music festival far south in a rural town called České Budějovice. Border guards raided the show, beating the crowds viciously. Hundreds were injured, and the band started having doubts.

About that time, Brabenec began interacting with other dissidents working secretly in Prague. Academics, writers, and philosophers gave underground lectures and circulated banned literature. A playwright named Václav Havel was the de facto leader of these dissident intellectuals. Havel became very important to the band. One night the band’s manager met up with Havel and hatched a plan. Havel would show up at their next concert and speak to the crowd. Their plan would never happen, as one of the bartenders— an informant—overheard their conversation and turned them in. The next day the entire band was arrested.

Art Creating Community

On the day of the trial, Václav Havel showed up at the courthouse with the entire dissident intellectual community. The underground music scene showed up as well. By arresting The Plastics and putting them on trial, the authoritarian leaders had inadvertently united the entire dissident community in Prague. They began talking together and making plans.

Brabenec and three other musicians were sentenced to eighteen months in prison. Yet, the most significant outcome was a famous manifesto called Charter 77, which criticized the government for refusing to implement the freedoms it had agreed to under the Helsinki Accords. The authoritarians responded with a brutal crackdown that only fueled the resistance.

Over the next decade the musicians and dissidents of Prague became more and more vocal. Eventually gathering nightly in Wenceslas Square, by the thousands, then tens and hundreds of thousands, demanding freedom and change. In 1989 the Berlin Wall fell. The entire Czech cabinet resigned, and within a month the playwright Václav Havel was elected president, and what came to be known as the Velvet Revolution ended communist rule in Czechoslovakia.

The Bible as Resistance Literature

After the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE, early Christians were scattered about the Mediterranean. Many fled north to Turkey and to modern-day Ukraine and Eastern Europe, though pretty much everywhere they went, early Christians found themselves living under the control of an authoritarian regime.

The politics of the day were a nightmare. However, the response of these early Christ followers was not an armed rebellion or the formation of a political movement. Instead, they began a period of incredible creativity. They wrote songs and hymns, constructed liturgies and prayers, wrote books and letters, innovated new forms of worship, and constructed new philosophies and theologies. Disempowered and oppressed by an authoritarian regime, Christianity underwent one of the most profoundly creative eras in church history, culminating in the construction of the entire New Testament.

Authoritarian Regimes Fear the Artist

The most striking aspect of those dark decades in Prague was not the content of artistic expression generated by the dissident community. The most potent factor was that the artists formed an underground community of joyful rebellion whose chief characteristic was a refusal to be downcast. They united around artistic expression and formed a community of hope that helped liberate the Czech people.

I don’t know where America is headed. I don’t know how successful Donald Trump and his MAGA cult will be in their attempts to rewrite the American story under the authoritarian banner. I only know this: every authoritarian regime fears the artist. Empires shrink before the artist because imagination is a danger to them. Artists can topple authoritarian regimes. It has happened before.