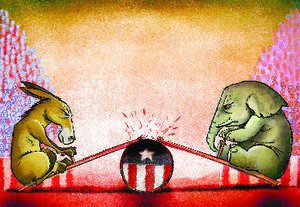

In the aftermath of the government shutdown, I’ve been reading quotes from Republican lawmakers, mostly senate Republicans, express frustration with the Tea Party. Nobody in Washington seems to be able to understand this bunch, much less work with them in any civil way. Many feel the Republican party is in the midst of a civil war.

In the aftermath of the government shutdown, I’ve been reading quotes from Republican lawmakers, mostly senate Republicans, express frustration with the Tea Party. Nobody in Washington seems to be able to understand this bunch, much less work with them in any civil way. Many feel the Republican party is in the midst of a civil war.

I’ve also been reading articles linking the Tea Party with fundamentalist religion. The idea seems to have first appeared at Bloomberg, in a post written by Francis Wilkinson. A more developed version came later, penned by Andrew Sullivan at The Dish. I think they are both worth a read.

There have long been considerations of the religious make-up of the Tea Party. Here’s an article from ABC News last year, and another from NPR in 2010, both of which cite the use of religious rhetoric – even apocalyptic themes. But the two articles yesterday are the first I’ve seen that characterize the movement itself as a religion.

Sullivan points out two elements of the Tea Party one must recognize in order to understand them. First, the Tea Party is a reaction against post-modernity:

“…The 21st Century has brought Islamist war to America, the worst recession since the 1930s, a debt-ridden federal government, a majority-minority future, gay marriage, universal healthcare and legal weed. If you were still seething from the eruption of the 1960s, and thought that Reagan had ended all that, then the resilience of a pluralistic, multi-racial, fast-miscegenating, post-gay America, whose president looks like the future, not the past, you would indeed, at this point, be in a world-class, meshugganah, cultural panic.”

“What the understandably beleaguered citizens of this new modern order want is a pristine variety of America that feels like the one they grew up in. They want truths that ring without any timbre of doubt. They want root-and-branch reform – to the days of the American Revolution. And they want all of this as a pre-packaged ideology, preferably aligned with re-written American history, and reiterated as a theater of comfort and nostalgia. They want their presidents white and their budget balanced now. That balancing it now would tip the whole world into a second depression sounds like elite cant to them; that America is, as a matter of fact, a coffee-colored country – and stronger for it – does not remove their desire for it not to be so; indeed it intensifies their futile effort to stop immigration reform. And given the apocalyptic nature of their view of what is going on, it is only natural that they would seek a totalist, radical, revolutionary halt to all of it, even if it creates economic chaos, even if it destroys millions of jobs, even though it keeps millions in immigration limbo, even if it means an unprecedented default on the debt.”

The second aspect of the Tea Party Sullivan notes is the one most interesting to me as a pastor. He says the movement behaves like a fundamentalist religion:

“This is a religion – but a particularly modern, extreme and unthinking fundamentalist religion. And such a form of religion is the antithesis of the mainline Protestantism that once dominated the Republican party as well, to a lesser extent, the Democratic party. It also brooks no distinction between religion and politics, seeing them as fused in the same cultural and religious battle. Much of the GOP hails from that new purist, apocalyptic sect right now – and certainly no one else is attacking that kind of religious organization. But it will do to institutional political parties what entrepreneurial fundamentalism does to mainline churches: its appeal to absolute truth, total rectitude and simplicity of worldview instantly trumps tradition, reason, moderation, compromise.”

Wilkinson’s take is similar:

The Tea Party is not easily pinned down, claiming the various mantles of an insurgency, a restoration and a mainstream movement of the silent majority — all at once. It bears some similarities to a more familiar kind of institution, as well: an upstart religion.

In “The Churching of America 1776-1990,” scholars Roger Finke and Rodney Stark surveyed booms and busts, entrepreneurialism, and monopoly in what they called the nation’s “religious economy.” An important thesis of the book is that as religious organizations grow powerful and complacent, and their adherents do likewise, they make themselves vulnerable to challenges from upstart sects that “impose significant costs in terms of sacrifice and even stigma upon their members.” For insurgent groups, fervor and discipline are their own rewards.

Right now, the Republican Party is an object of contempt to many on the far right, whose adamant convictions threaten what they perceive as Republican complacency. The Tea Party is akin to a rowdy evangelical storefront beckoning down the road from the staid Episcopal cathedral. Writing of insurgent congregations, Finke and Stark said that “sectarian members are either in or out; they must follow the demands of the group or withdraw. The ‘seductive middle ground’ is lost.”

No one would accuse Tea Party activists and politicians of being seduced by the middle ground. They demand a higher level of fealty to their goals than pragmatic middle-of-the-roaders can bear. And they justify their cause in explicitly godly terms — even the apocalyptic. The paradox of the Tea Party is that it wants to fight for the nation’s soul not from the sweaty storefront down the street, but from within the cool stone walls of the cathedral. Tea Partiers similarly believe they should rule the federal government from a back bench in the House of Representatives.”

That the conflict within the Republican party will continue to rage seems certain. Thanks to some potent gerrymandering, the Tea Party will likely remain a force in the House of Representatives for awhile, despite the fact that their unfavorables far exceed their favorables in recent polling. (Gallup: 17% of Americans consider themselves strong opponents of the Tea Party, contrasted with 11% who are strong supporters.) Another article (not as well done) at Huffpo links the religion and warring themes, an aspect Sullivan predicts as well:

“…this is not just a cold civil war. It is also a religious war – between fundamentalism and faith, between totalism and tradition, between certainty and reasoned doubt. It may need to burn itself out – with all the social and economic and human damage that entails. Or it can be defeated, as Lincoln reluctantly did to his fanatical enemies, or absorbed and coopted, as Elizabeth I did hers over decades. But it will take time. The question is what will be left of America once it subsides, and how great a cost it will have imposed.”

What do you think of the Sullivan/Wilkinson take? Is the Tea Party a fundamentalist religion?