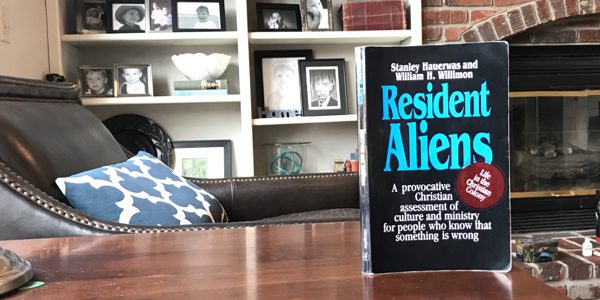

If I could require every Christian to read one book about the gospel, the church and what it means to be a Christian, it would be Resident Aliens. This spiritual classic by Stanley Hauerwas and Will Willimon has become one of the central texts for my life as a disciple and as a pastor. I teach adjunct at a local seminary and usually try to find a way to assign this as a text for pretty much any class I teach.

If I could require every Christian to read one book about the gospel, the church and what it means to be a Christian, it would be Resident Aliens. This spiritual classic by Stanley Hauerwas and Will Willimon has become one of the central texts for my life as a disciple and as a pastor. I teach adjunct at a local seminary and usually try to find a way to assign this as a text for pretty much any class I teach.

A few years back I began a new tradition. The week leading up to Palm Sunday I reread Resident Aliens. The book is a great preparation for talking about the dramatic clash between kingdoms symbolized by Palm Sunday.

The book is both simple, and really hard to get. I don’t know how many pastors I’ve talked to who have said, “Yeah, I read Resident Aliens. I love that book.” Yet their ministries are based on the very presuppositions Resident Aliens subverts. Chief among them being that Christianity is not a belief system. It is a new way to be human.

Resident Aliens makes one of the most profound critiques of Constantinian Christianity found in print. The idea is that when Christianity transitioned from being a fringe Jewish sect (often persecuted and never in power), to the favored religion of Constantine, the faith was fundamentally altered in many important ways:

Christianity became a civil religion:

No longer the faith of a peculiar people who followed the teachings of Jesus Christ, Christianity became the substantiating narrative for the Roman Empire, or a civil religion.

The Spiritualization of Christianity:

After Constantine Christianity vanished into the realm of the invisible, the private, and the personal. All beliefs were thereafter personal and private. This shift allowed Christian bodies to become co-opted by the state, and they ended up bearing the image of Rome—rather than the image of God—to the world around them.

Christian identity was established on new ground:

After Constantine Christian identity was no longer chiefly established, narrated, shaped, supported, passed on, and protected by the church. After this shift, all of those things would happen through the influence of the Roman Empire, and the surrounding culture. The resulting conflation of church and state resulted in further changes in the nature of Christianity, not the least of which was a loss of non-violence.

Loss of the non-violent foundation of Christianity:

Once the church became the official religion of Rome, it was joined to an enterprise that could not survive without violence and war. Non-violence could not be the official stance of the Roman Empire, because its existence, and the existence of the Pax Romana was dependent upon violence. Sadly, what Roman peace really meant was that they moved violence to the edge of the Empire and called the center peace. The City of Rome was nearly always at peace, but the edges of the Empire were in a constant state of war. That’s peace by the sword. It doesn’t eliminate war. It just moves it somewhere else.

Those aren’t the only implications, but you get the gist. I will be forever grateful to Stanley Hauerwas and William Willimon for their great book. Twenty-five yeas later and they are still printing copies of this baby.

Some quotes from the first half of the book:

“That which makes the church “radical” and forever “new” is not that the church tends to lean toward the left on most social issues, but rather that the church knows Jesus whereas the world does not.” 28

“Both [liberal & conservative Christians] assume wrongly that the American church’s primary social task is to underwrite American democracy. In so doing, they have unwittingly underwritten the moral presuppositions that destroy the church.” 32

“Aristotle argued that the primary purpose of the polis is the creation of people who are better than they would be without the aid of the polis. Yet what does our society, our polis, do to us? The primary entity of democracy is the individual, the individual for whom society exists mainly to assist assertions of individuality. Society is formed to supply our needs, no matter the content of those needs. Rather than helping us to judge our needs, to have the right needs which we exercise in right ways, our society becomes a vast supermarket of desire… what we call freedom becomes that tyranny of our own desires.” 32

“The church does not exist to ask what needs doing to keep the world running smoothly and then to motivate our people to go do it. The church is not to be judged by how useful we are as a supportive institution and our clergy as members of a “helping profession.” The church has its own reason for being, hid within its own mandate and not found in the world. We are not chartered by the Emperor.” 39

“The cross is not a sign of the church’s quiet, suffering submission to the powers-that-be, but rather the church’s revolutionary participation in the victory of Christ over those powers… the cross stands as God’s (and our) eternal no to the powers of death, as well as God’s eternal yes to humanity, God’s remarkable determination not to leave us to our own devices.” 47

“We would like a church that again asserts that God, not nations, rules the world, that the boundaries of God’s kingdom transcend those of Caesar, and that the main political task of the church is the formation of a people who see clearly the cost of discipleship and are willing to pay the price.” 48

“The church exists today as resident aliens, an adventurous colony in a society of unbelief.” 49

“When the only contemporary means of self-transcendence is orgasm, we Christians are going to have a tough time convincing people that it would be nicer if they would not be promiscuous.” 63

“The fundamental issue, when it comes to Christian ethics, is not whether we shall be conservative or liberal, left or right, but whether we shall be faithful to the church’s peculiar vision of what it means to live and act as disciples.” 69

“We are not advocating community merely for the sake of community. The Christian claim is not that we as individuals should be based in a community because life is better lived together rather than alone. The Christian claim is that life is better lived in the church because the church, according to our story, just happens to be true.” 77

“The Sermon on the Mount cares nothing for the European Enlightenment’s infatuation with the individual self as the most significant ethical unit. For Christians, the church is the most significant ethical unit… the church enables us to be better people than we could have been if left to our own devices.” 81

“The most creative social strategy we have to offer is the church. Here we show the world a manner of life the world can never achieve through social coercion or governmental action. We serve the world by showing it something that it is not, namely, a place where God is forming a family out of strangers.” 83

“Of course, we are forever getting confused into thinking that scripture is mainly about what we are supposed to do rather than a picture of who God is… the basis for the ethics of the Sermon on the Mount is not what works [pragmatism] but rather the way God is.” 85

“Therefore, Christians begin our ethics, not with anxious, self-serving questions of what we ought to do as individuals to make history come out right, because in Christ, God has already made history come out right. The Sermon is the inauguration manifesto of how the world looks now that God in Christ has taken matters in hand. And essential to the way that God has taken matters in hand is an invitation to all people to become citizens of a new Kingdom, a messianic community where the world God is creating takes visible, practical form.” 87

“Learning to be moral is much like learning to speak a language. You do not teach someone a language (at least nowhere except in language courses at a university!) by first teaching that person rules of grammar. The way out of us learn to speak a language is by listening to others speak and then imitating them.” 97