This essay was originally a sermon written for Redemption Church on November 09, 2014. If you are a pastor, feel free to copy and steal.

This essay was originally a sermon written for Redemption Church on November 09, 2014. If you are a pastor, feel free to copy and steal.

__________________________________

“Even powers that seem invincible are vulnerable to love, which is why God’s love has so often taken the form of the civil disobedience of God’s people.”

__________________________________

Somewhere around four hundred years had passed since Joseph interpreted Pharaoh’s dream and became Chief of Staff. In the Torah, Joseph is remembered as the man who helped save not only his family but also all of Egypt. As is often the case with great leaders, the memory of Joseph’s contribution faded over time, as did the privileged status the Israelites once knew.

Egypt was the richest nation, with the biggest economy, and the most powerful military on the planet. Yet they lived in constant fear. Egypt was always fighting a war of some kind. During the days of Moses, foreign invaders occupied Egyptian land to the East. Although their military was unparalleled, Egypt was vulnerable if the Hebrew people joined forces with an invading army. Pharaoh understood this, and took preemptive steps to make sure it didn’t happen. Anyone who was suspected of being disloyal was conscripted into forced labor camps.

This should all sound familiar to us. The United States is the Egypt of our world: the richest nation, with the biggest economy, and the most powerful military. We too live in constant fear—terrorism, Ebola, immigrants, failure, public speaking—you name it, we’re afraid of it.

Americans are fearful people. This is by design. We are told who and what to fear, because the powerful are constantly selling us the cure for our fears, usually involving violence of one kind or another. Fear is the necessary prerequisite for a policy of preemptive violence.

Whether it’s Pharaoh or Modern day America, this combination of great power and great fear is dangerous. An abundance of fear makes one worry about every little thing. An abundance of power makes one think they can do something about it.

This is the rationale of the helicopter parent: My kid makes me feel vulnerable. I don’t like that feeling. So I’m going to hover over this kid’s life, using all my powers to keep them safe. Never mind that the child is unable to make his own decisions, or even tie his own shoes.

When the powerful become fearful, they almost always fall for the illusion that they can make themselves safe. Typically this spells trouble for those who have little power at all.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor the fear which possessed many Americans involved the possibility of a Japanese attack on the West Coast. The fearful were also the powerful, so they authorized the detainment of around 120,000 Japanese men, women, and children in prison camps. Most of the detainees were citizens, many of their children enlisted, and nearly all of them were held without cause for almost 2 years.

So before we get all judgy with Pharaoh, let’s just remember how often we can all go to a similar place. Fear combined with power makes people do crazy things.

Exodus 1:8-22 Now a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph. He said to his people, “Look, the Israelite people are more numerous and more powerful than we. Come, let us deal shrewdly with them, or they will increase and, in the event of war, join our enemies and fight against us and escape from the land.” Therefore they set taskmasters over them to oppress them with forced labor.

They built supply cities, Pithom and Rameses, for Pharaoh. But the more they were oppressed, the more they multiplied and spread, so that the Egyptians came to dread the Israelites. The Egyptians became ruthless in imposing tasks on the Israelites, and made their lives bitter with hard service in mortar and brick and in every kind of field labor. They were ruthless in all the tasks that they imposed on them.

The king of Egypt said to the Hebrew midwives, one of whom was named Shiphrah and the other Puah, “When you act as midwives to the Hebrew women, and see them on the birthstool, if it is a boy, kill him; but if it is a girl, she shall live.” But the midwives feared God; they did not do as the king of Egypt commanded them, but they let the boys live. So the king of Egypt summoned the midwives and said to them, “Why have you done this, and allowed the boys to live?”

The midwives said to Pharaoh, “Because the Hebrew women are not like the Egyptian women; for they are vigorous and give birth before the midwife comes to them.” So God dealt well with the midwives; and the people multiplied and became very strong. And because the midwives feared God, he gave them families. Then Pharaoh commanded all his people, “Every boy that is born to the Hebrews you shall throw into the Nile, but you shall let every girl live.”

Pharaoh, with all his fear, and all his power, is determined to use his powers for good. This spells trouble for little guys. In this case our little guys are the Israelites.

The text says that Pharaoh has no memory of Joseph, or the debt the people of Egypt owed to the Israelites, which is important. Loss of memory often paves the way to the abuse of power. And fear nearly always leads to anger and oppression of some kind.

Not for nothing, but this is summed up well by the immortal wisdom of Yoda: “Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.” Fear is the most reliable path to suffering. Memory is one of the things that can keep us from going down that path.

Pharaoh’s systemic oppression didn’t work. Systemic oppression never works. “The more they were oppressed,” it says, “the more they multiplied and spread, so that the Egyptians came to dread the Israelites.” But Pharaoh had a plan: “When you act as midwives to the Hebrew women, and see them on the birth-stool, if it is a boy, kill him; if it is a girl, she shall live.”

The question for any serious reader at this point should be, why ask the midwives to do the dirty work? Pharaoh had an army of zealots who had no qualms committing mass infanticide against the Israelites. The implication in the text is that the midwives would be able to make the deaths look like stillbirths. Pharaoh hoped to trick the Hebrew people into thinking it was happening as a plague or judgment from their God. But the midwives, led by their two brave leaders, Shiprah & Puah, refused to carry out the Pharaoh’s command.

An interesting tension exists in the text regarding fear. Pharaoh was possessed by his own fear of the Hebrew slaves. Shiphrah and Puah, by contrast, feared God much more than they feared Pharaoh.

Now when I say they “feared God” I don’t mean they thought God was going to zap them or something. Today we’d say the had, “love & respect & reverence for God.” Fear was meant to connote the recognition of strength and power. The midwives respected and revered God more than Pharaoh. So they refused to comply with Pharaoh’s deathly order.

Pharaoh’s, as they say, don’t countenance no insubordination. So he calls the midwives on the carpet. They answer with a veiled insult that Pharaoh was too thick to catch. “See, how it works is, the Hebrew women are like pop guns. They give birth way before any of us slow-of-foot midwives can get to them.” Gumption. Everybody can see through the ruse except Pharaoh.

There’s actually a complex word-play going on here. The midwives use the words: ki-chayyot hey-nah. Now, to Pharaoh, with limited Hebrew, this phrase would’ve sounded like they were saying, “Hebrew women are like animals. They give birth quickly, and they don’t need assistance.” But Hebrew readers of the Torah would recognize a double entendre: chayyot comes from a Hebrew root meaning life. So, reading between the lines, the midwives were actually telling Pharaoh, “Hebrew women are too full of life to be contained by your plan, or treated in such a dehumanizing fashion.”

It was the first act of civil disobedience in the Torah. Shiphrah and Puah feared God more than Pharaoh, and thus refused to violate the most basic laws of human nature. Pharoah’s response was decisive. He ordered all of his people to do the job. Anyone who saw a male Hebrew baby was to throw it in the Nile. There were no attempts to conceal anything. There were only soldiers on patrol listening for the sound of babies, forcibly removing them from their mothers’ arms and drowning them.

It’s an incredibly callous decree… all that fear, and all that power.

It was also a self-defeating strategy, at least as far as public works go. Pharaoh was killing his most productive future workers. This is one of the many Ironic features crowded into this text; another being that powerful Pharaoh was forced to negotiate with lowly Hebrew midwives, who outwitted and mocked him, while Pharaoh remained oblivious.

Another ironic feature involves the fact that Pharaoh is never named in the text. The Hebrew midwives are named, but not Pharaoh. In ancient literature, that was a serious slight. The implication was that if these two women could defy the Pharaoh, maybe all of Israel could, too.

Shiphrah and Puah’s refusal to comply with an unjust decree is one of the most important acts of civil disobedience in the entire biblical narrative. The mode of their action seems important. There was no million midwife march. They didn’t make signs, or picket the capital. There were no slogans or chanting. They simply refused to comply with an unjust order.

Their action helps define civil disobedience: Refusing to go along with civil laws or customs that violate the laws of God.

The story of the Hebrew midwives has been repeated anytime the powerful have decided to assuage their own fears. Which means it has been most often repeated on Southern slave plantations, in Nazi death camps, during the abolitionist, and civil rights movements. Anytime Christians or Jews have gone against the grain of an unjust civil society this story has been a source of strength.

Christians are meant to be a community of resistance. In refusing to play by the rules of the culture, Christians unleash the subversive power of the gospel. That we so refuse is the evidence that we, like Shiphrah and Puah, fear God more than Pharaoh, or any power.

As we organize our common life together, our lives take on the shape of Christ’s life. This constitutes a real and present danger to the powers of our culture. The secret strength of civil disobedience is that it’s not a frontal assault. It’s a flanking maneuver meant not to destroy the enemy, but to convince the to lay down their arms and join the cause of justice and peace. Christians are meant to be culturally subversive.

Timothy Gombis, a New Testament scholar, says it this way: “We are subversive, then, in that we identify and resist the subtle cultural dynamics that work to shape us into just another community.” It’s a powerful distinction. We are not just another community. This isn’t Rotary, or Boy Scouts, or a book club. We are a community of resistance to the unjust powers of the world.

As we refuse to go along with injustice, the true colors of the oppressive power will emerge. They will become displayed for all to see, usually on the bodies of the innocent. Without the act of civil disobedience, the true colors of an oppressive power can stay hidden. If the midwives would have done as they were told, Pharaoh’s ruse could have worked. Since they refused, Pharaoh’s deep disdain for human life became obvious even to his own people whom he commanded to take part in mass infanticide.

God used that small act of non-compliance to begin a process culminating in the defeat of Pharaoh and the freedom of God’s people. At the time, however, Shiphrah and Puah did not know this. They were merely acting according to conscience, refusing to violate their sense of right and wrong. In so doing, they gave us a powerful picture of who God is. God is the God who has the back of the lowly and the powerless. God is the God who uses slaves and servants to save his people.

So, Pharaoh meant to kill all newborn Hebrew boys. We don’t know how many were killed in total. It was surely a gruesome number. What we do know is that there was one in particular he missed. Moses. H was the Hebrew Harry Potter: the boy who lived. That he lived as due to another brave act of civil disobedience.

Exodus 2:1-11 Now a man from the house of Levi went and married a Levite woman. The woman conceived and bore a son; and when she saw that he was a fine baby, she hid him three months. When she could hide him no longer she got a papyrus basket for him, & plastered it with bitumen & pitch; she put the child in it and placed it among the reeds on the bank of the river. His sister stood at a distance, to see what would happen to him

The daughter of Pharaoh came down to bathe at the river, while her attendants walked beside the river. She saw the basket among the reeds and sent her maid to bring it. When she opened it, she saw the child. He was crying, and she took pity on him. “This must be one of the Hebrews’ children,” she said. Then his sister said to Pharaoh’s daughter, “Shall I go and get you a nurse from the Hebrew women to nurse the child for you?”

Pharaoh’s daughter said to her, “Yes.” So the girl went and called the child’s mother. Pharaoh’s daughter said to her, “Take this child and nurse it for me, and I will give you your wages.” So the woman took the child and nursed it. When the child grew up, she brought him to Pharaoh’s daughter, and she took him as her son. She named him Moses, “because,” she said, “I drew him out of the water.”

Yokheved, his mother, hid Moses for as long as she could, probably until it put the whole family in danger. Then, working with his sister Miriam, she took a basket, coated it to make it water tight, and put her infant son in the basket. Then she complied with Pharaoh’s order. She threw the male infant it into the Nile hoping someone would find him and have pity on him. His big sister Miriam would stand guard and watch and try to help.

This section is also packed with irony. Pharoah’s means of killing—the Nile—became the means of Moses’ deliverance; foreshadowing the way Pharaoh and his army would one day be destroyed. It has always been a source of humor for the Hebrew people that Pharaoh was so afraid of Hebrew sons, when it was the Hebrew daughters who pulled off the plan that gave them Moses. Moses gets all the glory, but the daughters of Israel started the Exodus.

Women have had it rough in nearly all cultures throughout history. But in God’s economy, those who lack status according to culture, those who lack power because of the injustice of a society, are often those God will use. In God’s economy, cultural or political weakness is not a problem.

It is also ironic that the third act of Civil Disobedience comes from Pharaoh’s own daughter. Miriam hid in the rushes and jumped into action the moment the basket was discovered. She was there with a quick and easy solution the moment Pharaoh’s daughter was moved with compassion, providing more irony, by the way—Egyptian royalty being advised by Hebrew slave girls—this was not normal.

The climactic irony of the story was that Moses’ mother was not only allowed to raise her own child, she was paid to do so by Pharaoh’s daughter, which is to say by Pharaoh himself. All of this came with the promise that when Moses came of age he would not go off to make bricks, but would live at the palace. It is the ultimate irony. Pharaoh became the benefactor of the one who would soon take down his entire regime.

This is God’s economy. When we tell the story of the Exodus, the plagues, Red Sea, Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh typically get all the headlines. But in the Hebrew imagination the story is told with a different emphasis. To the Hebrew mind, the entire Exodus began with these five brave women & their acts of civil disobedience.

Shiphrah & Puah the midwives who refused to follow Pharaoh’s decree; Yokheved and Miriam creatively “throwing Moses into the Nile” so he would live on; Pharaoh’s daughter who saw the basket, heard the child, took pity & drew him out; all three of these are examples of simple acts of compassion that undid the power of Pharaoh’s empire.

Pharaoh built an invincible structure of unchallengeable power, but he had to oppress millions to do it. So he lived, as all dictators live, in fear that those who have been oppressed will one day rise up against their oppressors. The fear made him crazy. The power convinced him he could control the situation. But there was a crack in the cistern, very near its top. His own daughter was overcome by something as basic as compassion and love.

That’s the real problem with unjust power structures and human societies. They are always vulnerable to love. Throughout the story of God it has often been women who signify this most beautifully. Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, Miriam, Ruth, Esther, and Mary from Nazareth… these women are all symbols of love overcoming power, ant the least of these becoming the instrument of God’s deliverance and flourishing.

Even powers that seem invincible are vulnerable to love, which is why God’s love has so often taken the form of the civil disobedience of God’s people. This fact has been all but forgotten by most Christians in our society. The cracks in Pharaoh’s armor were exploited not by military force, but by non-compliance with injustice.

Most of us have little experience with this biblical theme, in large part because we have every advantage. Most of us live affluent lives with access to power, healthcare, education, wealth, employment, and opportunity. When the system works really well for one’s self, it’s easy become convinced that the system simply works. Civil disobedience isn’t a big concern among those the system is designed to serve.

Perhaps this is why Jesus required those who were powerful to be relationship with the poor, to care for the least of these, to speak for those who have no voice, and to care for the widow, the orphan, and the alien… and the alien. He who has ears, let them hear.

Civil Disobedience means refusing to go along with the powers that rule a society, formal or informal, when those powers go against the laws of God. No matter how good a system is, all systems are broken. Christians have to answer to God first, above any worldly power. When we are asked to bow to a false god, we refuse. When we are asked to dehumanize, or be inhumane, we refuse. And more than that, we try to find a way to point out the injustice.

This is true when it comes to big issues like immigration or racism or sex trafficking, and when it comes to every-day customs & practices of a civil society. Sometimes civil disobedience involves refusing to follow a law. But most of the time it’s refusing to bend to cultural norms. The most powerful actions will be small, & ordinary. That’s just how God rolls in this upside down kingdom.

Let me give a quick example. We’ve just come through a contentious election season. Kansas was a battleground state. One Monday night I was sitting with my boys watching a football game on TV. The most awful campaign smear ads kept showing up at commercial breaks. In our home we make fun of commercials as a matter of course. We talk back to commercials. Our standard line is, “Who you trying to kid?” It’s an effective retort to nearly any advertiser.

As we watched the never-ending political smear brigade, my kids noticed how much the political ads resemble movie trailers—the trailers we don’t let our kids watch. The boys kept turning away or closing their eyes because that’s what we’ve trained them to do with something inappropriate or scary comes on. I’d say, “You can watch this. It’s not scary, it’s just dumb.”

Even my children could sense how absurd this all was. After awhile, we decided to come up with our own dialogue. We’d turn the volume down to where you could still hear some of the music, and use our best radio announcer voice to say, “You won’t believe the awful truth we’ve just uncovered: Senator so-and-so eats puppies… that’s right deep fat fried puppies. In fact, So-and-so is not even his real name. His real name is Satan… that’s right Satan is running for the senate seat in Kansas.”

The best line of the night came from my oldest son: “Why doesn’t senator So-and-so ever show his forearm in public? I’ll tell you why. Because he’s a death eater, and he doesn’t want you to see the Dark Mark.”

That’s a small act of civil disobedience. For some reason the laws of our civil society say that it is okay to run political attack ads during Monday night football. As a Christian I disagree. So when those ads come on, I refuse to take part in them. I lampoon them instead, which has the added benefit of being enjoyable.

Just a quick aside: your convictions don’t have to be my convictions. I have a friend who refuses to watch football because it’s too violent. He can’t stand that predominantly poor kids play a game that causes serious brain injury. As a matter of conscience, he refuses to take part. That’s civil disobedience. I have similar worries, but my conscience hasn’t led me to the point where I think I should stop watching it. Nevertheless, my friend’s small civil disobedience bears witness to me. When I watch a game & see a particularly violent hit, I think of him, and I wonder, “Should I be watching this? Is this good for our society to worship sports like we do?”

That’s the power of civil disobedience. It helps us to see the way we have organized our common life from a different perspective, often from the perspective of those on the margins. Civil Disobedience is a peaceful protest, a refusal to comply with certain laws & customs because we fear God more than we fear civil rules and customs. Civil disobedience mimics the life of Jesus. Since it is peaceful, it leaves the door open for the opposition to become a friend.

Churches need to be really good at civil disobedience. Churches must learn to name injustice, and find ways to creatively resist it. Even if we don’t agree with our fellow church members, we can support each other and listen and learn from each other. This should be seen not as political activism, but as an act of worship of the one true God, (which is why the church cannot afford to participate in American party politics).

No matter is too small. You have no idea how a small act of defiance might end up being a big deal somewhere down the road.

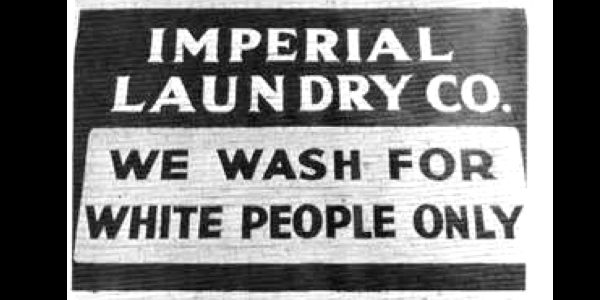

One of the great examples of this in our history is Rosa Parks. When she got on the bus after work that fateful day in Montgomery, Alabama, she wasn’t thinking about changing the world. She was thinking about getting home and cooking dinner. However, Parks was prepared to resist evil. She had been trained in non-violent civil disobedience by her church.

Contrary to popular thought, Rosa Parks did not sit in the white’s only section of the bus that day. She sat in the colored section. But after a few stops the bus filled up, and a white man was left standing. The bus driver said: “Y’all better make it light on yourselves and let me have those seats.” That particular driver, a man named Jim Blake, had a reputation for being harsh & crude. All that fear and all that power… he was so sure he was in control.

Rosa Parks had previous encounters with Jim Blake. The Montgomery buses had a front door and a back door. Non-white riders were required to go in the front door, pay the fare, get off again, go to the back of the bus, and enter through the back door. A few months earlier Rosa Parks went to the front to pay her fare, got off to go to the back of the bus, and this very driver, Jim Blake, took off and left her standing there on the street. Rosa said if she had been paying attention to who was driving that day, she would’ve waited for another bus. But she got on the crowded bus that day.

The driver barked his calloused order not to a group of four riders, one of whom was Rosa Parks. The other three got up and moved, but Rosa just sat there. The driver turned around and said: “Why don’t you stand up?”

Rosa said politely, “I don’t think I should have to stand up.”

He said, “Well, if you don’t stand up, I’m going to have to call the police and have you arrested.”

Rosa simply said, “You may do that.”

It was the biggest mistake of Jim Blake’s life. She was arrested and jailed for not giving her seat to a white man. Community leaders organized a boycott of the buses the next day. The boycott lasted 381 days. Rosa’s one little act of civil disobedience fired the civil rights movement for years.

What many choose to ignore is that Rosa Parks was a devout Christian. She was part of the church for her entire life, and her faith grounded her in the story of civil obedience. Once, when she was asked how her faith impacted that act of civil disobedience, Parks said: “From my upbringing and the Bible I learned people should stand up for rights, just as the children of Israel stood up to the Pharaoh.”

This is the line Christians have always drawn from a contemporary injustice to the story of the Exodus. And the simple fact is that it is nearly impossible to draw that line when you are in power. Southern Christians have yet to answer for the fact that they spent a long time on the wrong side of the civil rights issue. Many Christians in our society today will have to answer for the treatment and attitudes toward immigrants, documented or otherwise. This is why Jesus commanded those in power to be in relationship with those who do not have power.

As Christians, our first allegiance is to Christ, and God’s Kingdom. Our job is not to destroy our enemies, but to win them over to God. These little acts of civil disobedience my seem insignificant. But we are taught to believe that, through God’s power, the little things we do are cosmically significant. You and I cannot know how the small thing we do to resist the powers of darkness today will impact the world of tomorrow.

My prayer is that we’ll look at the lives of these saints: Shiphrah, Puah, Yokheved, Miriam, Pharaoh’s daughter, and Rosa Parks, and see in their lives an example that we can all follow.