This is a guest post by Sheila Marie Connolly, who agreed to write about her grandfather as part of my Four Weeks of Fine Men series. Thank you, Sheila!

This week, I saw a re-enactor pretending to be my grandpa. His plane was being installed in a new park, with a plaque describing him as “Lieutenant Colonel Colin A. Clarke, recipient of the Air Force Cross.” The re-enactor talked about the mission Grampy had flown, how he flew for nine hours in his fighter plane leading a rescue of two downed pilots, despite adverse conditions and hostile fire.

And it’s true, he did do all that. He was shot down twice in Vietnam; he was Top Gun in flight school; he also won the Silver Star and won the Distinguished Flying Cross three times. You could make a great movie about Grampy.

But to me that wasn’t what he was at all. I knew him as a calm, quiet man who always had time for his grandkids. Where other adults would pepper the shy child I was with constant questions, he would just invite me to join him with whatever he was doing. Sometimes we would dig together in his garden, where the soil was so fluffy that if you stepped in it, you left deep footprints. Sometimes I would sit on a stool in his shop, watching him solder together pieces of an airplane wing. Sometimes he would take me soaring in a glider–so much quieter and slower than a plane. He always made me take the stick. If I was scared, he’d say, “Well, I let go of the stick, so if you don’t want to crash, you’d better take it.” He had a way of making you feel brave, just by how brave he was. If he wasn’t scared to be in a plane piloted by a ten-year-old, why should I be?

Grampy wasn’t a guy to sit on the couch. He ran marathons when he was younger, and when he was older he barely slowed down. He liked to find out what my grandma wanted and just get it done. She didn’t like the tree in the yard? Down it comes. She wanted built-in lighting over her counter? Sure, he’d figure out how. Their cabin on the lake was full of tiny details he made for her: stonework hand-fitted together, built-in bunk beds for the grandkids, beautiful carved birds’ heads to hang your towels on.

He wasn’t a big talker, but that didn’t mean he was impassive. He laughed hard, he made silly faces, he always licked the ice cream bowl and then offered it to my grandma with a teasing, “I cleaned it for you, dear!” He wasn’t embarrassed to cry when he was sad. My mother always told me to marry a man who could cry, like her father did. And I think there’s a lot of truth to that. A man who can cry can process the trauma of war without letting it out in anger, like so many Vietnam vets did. I know the things he saw made a deep, painful impression on him, but I also know he rarely raised his voice and never swore. My mother says he never had to raise a hand to his three children. He would simply raise his eyebrows and they just knew it was time to shape up.

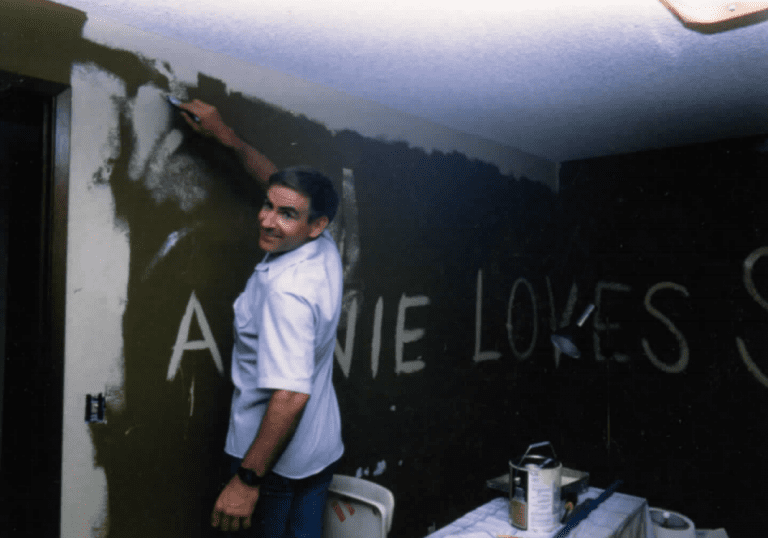

Sheila’s grandpa painting “Arnie Loves Sandra” on the wall while getting their home in shape to move in.

Sheila’s grandpa painting “Arnie Loves Sandra” on the wall while getting their home in shape to move in.

Our family loves to share stories of his fearlessness and determination. For instance, when he tried to join the Navy, he was turned away for being too short. But instead of giving up, he built a makeshift rack to stretch himself to reach the height requirement. Week after week, he’d stretch himself and then hurry down to the recruiter to try to sign up. It never worked, but an Air Force recruiter happened to meet him and suggest a different career for him, and the rest is history.

As for his courage, he simply never panicked. One time my father was flying with him, just a fun flight for Grampy to enjoy with his son-in-law. But the engine burst into flame while they were in the air. My dad looked at Grampy, saw Grampy wasn’t bothered, and figured there was no need for him to panic either. ampy, saw Grampy wasn’t bothered, and figured there was no need for him to panic either. Flames were billowing around the canopy and up around the stick, but my dad assumed it was all under control until they were coming in toward the runway and Grampy asked calmly, “Do you think we’re going to make it?” Both men escaped with only bruises from their seatbelts, but without Grampy’s calm, quick thinking, they could have died. My dad’s comment was, “There is no safer place than in a burning aircraft with your grandpa.”

In a letter, my mother once asked him how he coped with the fear of war and being shot at. Did he pray? His answer was this: “Until experienced, the reaction to fear is one of our internal big questions – I’m happy with my answer to myself. The worst thing that can happen is not death but to lose faith. My personal conversation with God isn’t very verbal – I think I accepted God before I had good verbal skills and haven’t written or talked to Him so much as felt that He is with me.” I think perhaps part of his calm under pressure was the confidence of feeling he wasn’t alone in the cockpit.

He’s not with us anymore. He died the year my first child was born. I wish they could know him; I want nothing more than for them to grow up with his determination, courage, and kindness. I have to make do with telling them story after story. I want them to know that you can be a hero without letting it go to your head; that you can earn the respect of others without boasting, simply by working hard and letting your actions speak for themselves; that you can be calm and gentle without being a pushover; that you will always be remembered for how you were there for a child, not for how many enemy planes you shot down. If my sons grow up with a little of the “old man” in them, I’ll be proud.

– Sheila