Grane draws a comparison between the anti-abortion pro-life cause and the historical abolition movement, writing:

The heart of the life issue is simple: Should the government let individuals take human lives in pursuit of their sexual freedom? That’s what abortion is. It was foisted on America by unelected judges, and dangled out of the reach of citizens and voters. So laymen rose up, with a little assistance from clergy, and chose to fight. In much the same way, 150 years ago, Christians looked at the unjust laws permitting slavery, and formed the abolitionist movement.

And today as in 1830, many chose not to fight… Instead they developed the elaborate, tortured rationalization that we call the Seamless Garment.

The problem with this characterisation is that Grane is wrong about historical abolitionism.

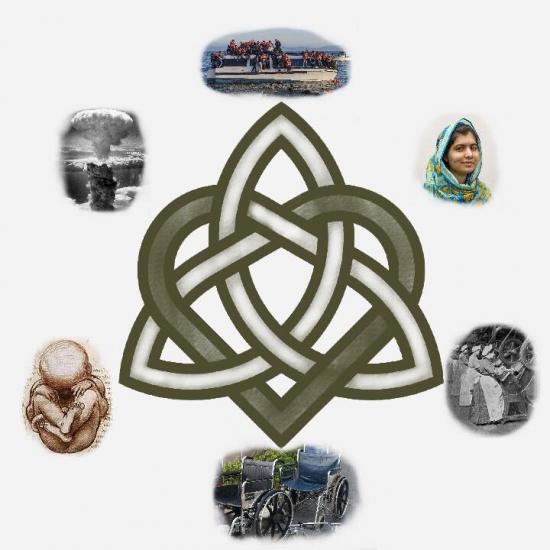

Christian abolitionists did not confine themselves to the single issue of slavery or understand abolition in isolation. The Christian abolitionist movement was part of a larger evangelical push to apply the principles of Christian brotherly love through social and political reform.

This movement was heavily influenced by several theological strains spread during the Second Great Awakening in North America and the UK that emphasised personal and social accountability for sin, works as evidence of salvation, and, in some cases, believed Christians were called to bring about God’s Kingdom on earth in preparation for the Second Coming (postmillenialism).

It should be hardly necessary to point out that many prominent abolitionists in the US and the UK were Quakers, whose religious commitment to pacifism became, over time,** the basis for a continuous and ongoing tradition of social activism.

Across US and UK society, abolitionism was part of a rising tide of reform activism that also included calls for temperance, women’s rights, child welfare, prison reform, labor reform, and improved care for the handicapped, orphaned, and elderly. In the UK, abolitionism was promoted politically alongside calls for amendments to the Poor Law–the legislation that created the workhouses of Dickensian infamy. Years later, the sense of solidarity between these causes was exemplified again when the suffering mill workers of Manchester passed a resolution supporting the embargo against Confederate cotton–in the midst of a famine caused by that blockade.

*Link leads to an archived version of the article, both for lasting posterity on a website known to “dirty delete” and post-edit articles, and (more especially) to avoid giving said website additional traffic and revenue.