At the New York Review of Books blog, Garry Wills recently asked some important questions about Mormonism and the Constitution. Recalling discussions he had with an LDS student two decades ago who believed that America’s two founding documents, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, were both inspired, Wills raised several provocative questions: Should every section and article of the original Constitution—including those that perpetuated slavery—be considered inspired? If the text constructed in 1787 was inspired, why did it require later amendments? How does viewing the document as inspired make one approach it differently than those who view it as a pragmatic compromise written by intelligent, if still flawed, politicians? And, most importantly for today’s political world, would this have any bearing on Mitt Romney’s presidency?

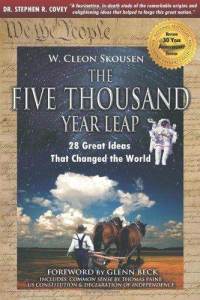

Though there were some unfortunate mistakes in Wills’s post, his former student is far from alone amongst Latter-day Saints in sacralizing the Constitution and America’s founding. Wilford Woodruff, who served as an apostle (and later, president) for much of the nineteenth century, claimed a visitation from the spirits of America’s Founding Fathers who requested proxy baptism at his hands. Twentieth century Mormonism has produced figures like Arnold Friberg (who painted the famous Prayer at Valley Forge) and Cleon Skousen (who wrote the popular Five Thousand Year Leap), just as the twenty-first century produced Glenn Beck and Jon McNaughton. Ezra Taft Benson, who was President of the Church at the time of the Constitution’s bicentennial in 1987, remarked, “I reverence the Constitution of the United States as a sacred document. To me,” he continued, “its words are akin to the revelations of God, for God has placed His stamp of approval on the constitution of this land.” Even today, Mormon homes in America often hang framed portraits of their nation’s figures and moments alongside the Church’s Proclamation on the Family and The Living Christ.

But there’s a problem: I’m not so sure this understanding is backed up in Mormon scripture and theology. I’m also not sure what role, if any, this patriotic theology will have in an increasingly international church. One thing I am sure about, though, is that this traditional—and parochial—reading of LDS theology is both a reflection of and extension from a vibrant American tradition of infusing contemporary culture with scriptural reading and religious belief.

The Mormon divinization of America’s founding documents has a complex history, based on a few vague references in the Book of Mormon, some explicit verses in Joseph Smith’s revelations (now contained in the Doctrine and Covenants), and a long tradition of LDS leaders interpreting these texts in attempt to sacralize American originalism. Yet a closer reading of LDS scripture finds many of these claims quite tenuous. The Book of Mormon primarily speaks of a chosen “land” rather than a chosen government—and many Mormons now claim that the land upon which the ancient narrative took place was Central and South America rather than what is now the United States, making connections to American exceptionalism all the more sketchy. And Joseph Smith’s two revelations that touch on the topic, received in the immediate context of being expelled from Jackson County, Missouri, seem to merely valorize the religious liberty clause in the Constitution—an important principle to Saints who were then being persecuted for their faith—as opposed to what the document dictates concerning, say, the size of government or the legality of universal healthcare.

But these exegetical limits have not stopped interpretive and eisegetical extensions. From these seeds of scriptural nationalism has sprouted an energetic tradition of Mormon patriotism. Though the nineteenth century witnessed a dynamic relationship between the LDS Church and America, increased attempts at assimilation following Utah statehood gave rise to an increased commitment to national mythos, including participation in founders-worship and the insistence of America as a Christian nation.

Importantly, Mormonism sought to emerge from a fringe sect to an American institution just as the country was developing a robust—and in some ways, anti-intellectual—response to pluralism, secularism, and the culture wars. The complexities and fragmentation of the mid-twentieth century spawned a conservative impulse that sought for unity through the fundamentalist mindset and belief that the answer to contemporary problems was a return to religion. This ideological turn had wide-reaching ramifications in religion, society, and, especially, politics. The period witnessed a cultural merging of provincialism and patriotism, with manifestations ranging from the addition of “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance to the adoption of “In God We Trust” as the national motto.

Mormons like Ezra Taft Benson and Cleon Skousen freely took part in this movement by associating with similarly minded groups like the John Birch Society. Built upon a cultural tradition that already emphasized the importance of the past and the allegiance to leaders, as well as a theological tradition that located sacred sites like the Garden of Eden and the Second Coming as taking place in the continental United States, Mormons were poised to partake of and contribute to divine nationalism. LDS discourse came to mirror the fundamentalist patriotism of post-World War II America, in messages delivered both from its pulpit a well as in print.

Simultaneously, Mormonism entered their process of correlation, a movement that not only streamlined church practice but also crystalized the period’s cultural image. By centralizing ideological authority and systematizing Mormon belief, correlation in essence froze the church’s persona to a moment in time: the hyper-patriotism of conservative America in the 1960s and 70s. While the LDS message has progressed—and will progress—since then, such progression has been slow, unsteady, and still imbedded in the framework in which the modern Mormon image was birthed.

These cultural tensions have certainly played a role in how Mormons read their scripture and imagined their country. The Book of Mormon in particular has been interpreted and reinterpreted throughout the last two centuries, often assuming a discursive life of its own. The very nature of scriptural reading often incorporates the readers’ assumptions and ideals, especially in a tradition that has lacks a formal clergy and relies primarily on amateur hermeneutics. Just as Christianity’s reading of the bible has evolved over the past two millennia, so too has Mormonism’s scriptural interpretations adapted to new cultural norms. It should be expected, then, that a predominantly American religion would read national patriotism into their sacred texts.

But it should also be expected that this merging of Mormon theology and American exceptionalism would not last forever. Besides the inevitable adoption of more sophisticated readings of Americanism, as seen with Apostle Dallin H. Oaks’s 1992 caution that too much “reverence” for the Constitution leads to mistaking it for scripture, Mormonism’s aspirations to be a global religion will probably entail a reframing of Mormon scriptural theology that is divorced from American culture. Though church headquarters may remain in Salt Lake City, Utah, the explosive growth of Church membership throughout the world (especially in southern hemisphere areas like Brazil), the internationalism found in the church’s leadership (even if it hasn’t reached the highest levels), and the desire to transcend local culture will likely distill a more cosmopolitan—and less parochial—flavor.

The implications this international shift will have on how American Mormons—including Mitt Romney—understand their country is unclear. The predominantly local nature of LDS practice may very well perpetuate an American cultural reading of Mormon scripture within the United States. But such interpretations that sacralize America will most likely become increasingly challenged and nuanced.

In many ways, it may end up that Romney’s particular political persona, in which he acknowledges the importance of his religion but doesn’t specify its relationship to his patriotism, will be the future of Mormon nationalism.