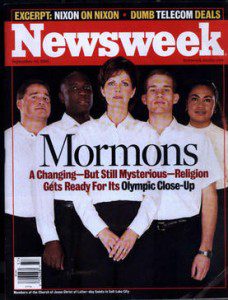

A decade ago, during the last “Mormon Moment” when the Winter Olympics were held in Salt Lake City, Newsweek ran a cover story about Mormonism that represented it as fundamentally conformist, where men and women of different races all wore identical white shirts and black slacks. The image suggested that beneath the apparent racial diversity of modern Mormonism, there remains a culture of obedience and conformism. The photograph was an image of Mormonism’s enduring symbolic place in American history as an opponent of individualism and diversity.

A decade ago, during the last “Mormon Moment” when the Winter Olympics were held in Salt Lake City, Newsweek ran a cover story about Mormonism that represented it as fundamentally conformist, where men and women of different races all wore identical white shirts and black slacks. The image suggested that beneath the apparent racial diversity of modern Mormonism, there remains a culture of obedience and conformism. The photograph was an image of Mormonism’s enduring symbolic place in American history as an opponent of individualism and diversity.

A decade later, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints remains defined by this image of conformity, but now seeks to both embrace and resist it. There remains a fundamental tension with the Church’s projection of its own image, celebrating both individualism and uniformity. On one hand, the now ubiquitous “I’m a Mormon” ad campaign emphasizes the real life diversity, spontaneity, and quirkiness of Mormons as interesting people. On the other hand, if you were to follow up on one of those ads, two young men, probably white, probably from the Western US, wearing near identical uniforms would show up at your door. Mormonism wants to embrace its diversity but the images of conformity remain central to how it presents itself.

Mormonism’s ambivalent relationship to the stereotypes about conformity, uniformity, and a kind of bland wholesomeness is reflected in the criticisms it faces from outsiders and some members alike. In certain social circles, sometimes Mormons are treated as the exception to the stereotypes, or even project their status as the lonely “good Mormon” swimming against the tide of Mormon conservative conformity. (This trend is somewhat reminiscent of the famous That Mitchell and Webb Look’s comedic send up of the parable of the good Samaritan.)

The image of Mormon conformity to some imagined ideal not only engenders its uglier cousin, the stereotype, but also fails to accurately capture Mormonism as lived religion. Any categorizations and generalizations should be met with serious and sustained scrutiny. There are notable Mormon artists, actors, entrepreneurs, educators, poets, aid workers, ambassadors, operators of women’s shelters and schools, musicians, and just about anything else. There are Mormon vegans, punk rockers, hipsters, bikers, skaters, gamers, addicts, special Olympians, and more. Mormonism does not produce homogenous automatons, but real human beings, with all the good and bad that entails.

At worst, Mormon uniformity and conformity are taken as the sign of the c-word, cult(!), surprisingly still a term hurled by some evangelicals and liberals alike. Such an assertion can only be made when one reduces Mormon experiences, worldview, or otherwise otherizes Mormonism as distinctly not “like us.” To resist Mormon stereotypes is not only in the service of Mormons, but contains within it a larger lesson about the failure of labels and shorthand generalizations about others, like “gays,” “blacks,” “Asians,” “immigrants,” and other powerful categories that exist in the American imagination. Such easy ways of making judgments about large and complex groups of people may function as common ways of making sense of the world, but they fail any ethical standard and empirical experience.