While Memorial Day in the United States is an opportunity to cultivate memory of all kinds—remembrance of ancestors, family, and departed friends—it is often used to memorialize courage, and even heroism. Whatever the politics of the war in which they died, for instance, most Americans honor war dead for the courage it took to endure the peril of conflict. And the valorization of courage extends to Mormons in the United States as well. On Memorial Day many Mormons (particularly those in and around the Intermountain West) reflect on the nineteenth-century era of the westward migration, in which Mormons braved an overland exodus that proved harrowing for many and fatal for some. The heritage of Mormon courage is an open canon, though, and there are many narratives of moral courage for Mormons to commemorate, stories like that of Helmuth Hübener.

While Memorial Day in the United States is an opportunity to cultivate memory of all kinds—remembrance of ancestors, family, and departed friends—it is often used to memorialize courage, and even heroism. Whatever the politics of the war in which they died, for instance, most Americans honor war dead for the courage it took to endure the peril of conflict. And the valorization of courage extends to Mormons in the United States as well. On Memorial Day many Mormons (particularly those in and around the Intermountain West) reflect on the nineteenth-century era of the westward migration, in which Mormons braved an overland exodus that proved harrowing for many and fatal for some. The heritage of Mormon courage is an open canon, though, and there are many narratives of moral courage for Mormons to commemorate, stories like that of Helmuth Hübener.

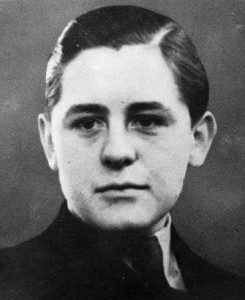

Hübener was a German teenager who mounted a small-scale information resistance campaign to Nazi social and political propaganda during World War II. He was arrested by the Nazi Gestapo, endured beatings while incarcerated, made a defiant appearance in front of a Nazi blood tribunal, and finally suffered a guillotine execution in the bowels of a German prison. He was the youngest person to be formally tried and executed by the Nazi regime. After his death and the war, Hübener became a folk hero of the German resistance, memorialized in German literature. Over the last few decades, with new scholarly attention, his story has become better appreciated by fellow Mormons elsewhere in the world.

Born in Hamburg in 1925, Hübener was a precocious, articulate teenager with wide interests in history, geography, politics, and music, and spoke English fluently. His intellectual promise had opened the way for an a promising career at the German civil service. When he was sixteen, however, Hübener came into possession of a contraband short-wave radio, a development that changed his life dramatically. German radios at the time were carefully manufactured to prevent citizens from encountering foreign broadcasts, but through his engineer brother, Hübener gained access to a French shortwave radio, and thereby to the English and German language broadcasts from the BBC. Almost immediately, based on his own comparisons of foreign reports and the reporting of the German state, Hübener became convinced that Germany was on the wrong side of the war. Stirred up by this discovery, he organized clandestine listening sessions with a few close teenage friends.

Within a few months, Hübener hatched a plan to disseminate what he had learned, evidently well aware of the risks this entailed. Later he testified that once he became aware of the misinformation being foisted on Germans by their government, he felt compelled to share the truth with others. As a clerk of sorts for the local Mormon ward, Hübener had access to the congregation’s typewriter, which he borrowed despite the ardent pro-Nazism of the branch president; he told his friends that their only real crime was stealing paper from the ward’s supply. Once the leaflets had been prepared, Hübener and two associates discreetly spread them the around the city, taking care not to be seen. They slipped them into mailboxes and coat pockets, planted them in telephone booths, and posted them on public billboards. (In time, Hübener began camouflaging handbills as official Nazi bulletins.)

Beyond circulating the news of broadcasts, in the leaflets Hübener articulated his own critiques. He denounced the mendacity of the German government, challenging its propaganda narratives of military success and economic strength. He also produced aggressive criticism of Hitler himself in pamphlets with titles like “Hitler the Murderer.” The writing revealed a penchant for language and wordplay: Hübener wove in German folk myths and citations of Shakespeare. He tweaked Hitler’s title from “Führer,” leader of the people, to “Verführer,” defiler or seducer of the people. And he railed against the anti-Semitic atheism he saw promoted by Nazi propagandists.

After surprisingly long run of eight or nine months, the resistance effort finally imploded. Attempting to enlist others to help expand the effort, Hübener was reported to a work supervisor (also a surveillance agent), and then to the Gestapo. A swift investigation turned up incriminating evidence and put Hübener and his associates in jail. Initially unwilling to believe that Hübener had been acted without oversight, investigators applied torture in an effort to extract confessions. During trial, impeccably documented in the Nazi way, Helmut seemed resigned to his fate and defied the tribunal. Asked if he believed that Germans were lying, he simply responded “Aren’t you?” And when sentenced to death, he pointed at the bench and answered: “Wait. Your turn will come.”

One letter survives, written to a family friend on the day of his execution:

I am very thankful to my Heavenly Father that this agonizing life is coming to an end this evening. I could not stand it any longer anyway! My Father in heaven knows that I have done nothing wrong. I know that God lives and He will be the proper judge of this matter. Until our happy reunion in that better world, I remain,

Your friend and brother in the Gospel,

Helmuth

Further reading:

-

Alan F. Keele and Douglas F. Tobler, “The Fuhrer’s New Clothes: Helmuth Hübener and the Mormons in the Third Reich,” Sunstone 5, no. 6 (November/December 1980): 20–29.

-

Karl Heinz Schnibbe, Alan Keele, and Douglas Tobler, The Price: The True Story of a Mormon Who Defied Hitler (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1984).

-

Blair R. Holmes and Alan Keele, When Truth Was Treason: German Youth Against Hitler (University of Illinois Press, 1995; repr. Academic Research Foundation, 2003).

-

Rudi Wobbe and Jerry Borrowman, Three Against Hitler: A Compelling True Story of LDS Teens’ Fight for Freedom (Salt Lake City: Covenant Communications, 1996).

-

Richard Lloyd Dewey, Hübener vs. Hitler: A Biography of Helmuth Hubener, Mormon Teenage Resistance Leader (Academic Research Foundation, 2004; repr. Stratford Books, 2012).