On June 2, the University of Illinois Press released my first book, Kirtland Temple: The Biography of Shared Mormon Sacred Space. For my post this month, I thought that I would give the readers a small sampling of my new work. While most of my book covers the Kirtland Temple in the twentieth century, the following excerpt is drawn from my first chapter that narrates the emergence and uses of the temple in the 1830s and 40s. This excerpt pays particular attention to how Joseph Smith created a multifunctional sacred space that would subsequently unify and divide his followers. For readers desiring an early review of my book as a whole, they may find one on religious studies scholar Thomas Bremer’s website located here. Enjoy!

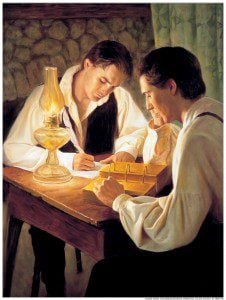

The seventy-year-old matriarch of Mormonism’s first family, Lucy Mack Smith, composed a now-famous family memoir in 1845, less than a year after the deaths of three of her sons, all leaders in the early Mormon church. In an early chapter, Lucy recalled a scene from the previous decade where Joseph, her middle son and founder of the movement, led a meeting of Mormon priesthood members at Kirtland, Ohio. The gathered priesthood solemnly considered “building another meeting House,” Lucy recalled, “as the first was now rather small to afford room for the increased congregation. . . . Some thought that it would be better to build a frame [house],” she continued, while “others said that a frame [house] was too costly kind of a house—and the majority concluded upon the putting up a log house.” Then, as if waiting for the right moment to arrive, “Joseph rose and reminded them that they were not making a house for themselves or any other man but a house for God[.] And shall we brethren build a house for our God of logs[?]” To this rhetorical question, Lucy’s Joseph dramatically responded, “No brethren I have a better plan than that[.] I have the plan of the house of the Lord given by himself.” [1] Rather triumphantly, Joseph “gave them the plan in full of the house of the Lord at Kirtland which when the brethren heard they were highly delighted.” Although the minutes from the likely meeting that Lucy recounts do not record the dialogue that she composed in her memoir, Lucy Mack Smith provided a dramatic explanation for the origins of the Kirtland Temple that would have resonated deeply with her fellow nineteenth-century Mormons. Lucy’s Joseph Smith had a pattern for the temple given to him straight from heaven—a shorthand explanation, incidentally, for how Mormons came to believe that most of their church’s rituals, teachings, and ecclesiastical offices emerged, too. Perhaps most importantly, Lucy’s Joseph Smith unified his community with the pattern of the temple. Where there once was debate and confusion, Smith, through the pattern of the temple, brought order and peace.

If early Mormons were a people who believed they were given a divine “pattern” from heaven in all things, they were also a people who believed they were “prepared” by God by their previous experiences to receive such divine knowledge. Here, the context in which early Mormons lived was crucially important to them, as it is in different ways for modern historians who seek to explain early Mormons within their antebellum American setting. When early Latter Day Saints used the word “temple,” they already had a working conception of what that word meant. In Bourdieu’s terms, early Latter Day Saints carried with them a “habitus” that included the term “temple,” as well as bodily expectations of what could be experienced in such a holy place. The shared cultural matrix of early Mormonism affected how Mormons interpreted and acted upon Joseph Smith’s revelatory reworking of an antebellum evangelical concept of a temple. Of course, emphasizing a shared cultural matrix glosses over the manifold differences that early Mormons also held with one another.

Living in an age that celebrated religious choice and trusted individual experience, early Mormons could be a fractious bunch, prone to constant schism. Smith attempted to use temples as places that would unify his people and quiet the cacophonous religious diversity that besieged his weary antebellum American followers. In his temples, Smith hoped that his adherents would create everlasting sacramental bonds and obtain charismatic powers that would enable them to convert the world. However successful Smith was in unifying and expanding his church through his followers’ experiences in his temples, Smith created sacred spaces that paradoxically exacerbated the possibility of schism within his movement.

Smith created temple spaces that liberally mixed emerging public and private realms—spaces for democratic dissent with spaces for private religious ritual, spaces for public education with spaces for exclusive priestly education, and spaces for tourism with plain spaces for worship. The mixing of public and private was not so much a problem as the number and range of activities that could be done within a temple. To use an artistic metaphor, Smith’s sacred spaces were not so much painted icons with established, routinized images but vast murals so teeming with physical activity as to overwhelm the viewer with the manifold possibilities of meaning. The ecclesiastical successors who would follow Smith expanded upon the uses he established for temples, but only by building upon certain functions while ignoring others. A genealogical tracing of evolving experiences in and expectations about temples provides insight into why divisions would develop within Mormonism during and after the life of its founder. The Mormons’ preparation within the walls of the Kirtland Temple, then, led to centrifugal conflict as much as it provided shared experiences that held them together.

From Kirtland Temple: The Biography of a Shared Mormon Sacred Space by David J. Howlett. Copyright 2014 by David J. Howlett. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

[1] Lavina Fielding Anderson, ed., Lucy’s Book: A Critical Edition of Lucy Mack Smith’s Family Memoir (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2001), 580–81.