Written on Memorial Day, 2014

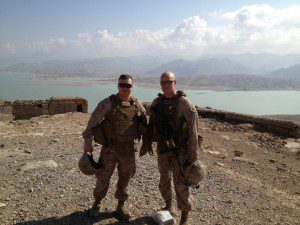

This is my first Memorial Day home after combat. In Afghanistan, I prayed over the injured, the dying, and the dead—and I suppose it’s fitting to pray for all of them again, today. I’m not as haunted by the dead as I am by these words, which I often heard when a casualty came in and a Marine or Sailor would respond, “Don’t worry, Chaps: it’s only an Afghan.” I suppose the moral wounds are greater than the physical.

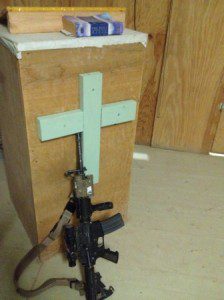

As a military chaplain endorsed by Community of Christ, I’m always uneasy with my church’s mandate to proclaim peace, and with my commission in a war-fighting force, even if I am a noncombatant. But Memorial Day reminds me that even those opposed to war (should) support the individual humanity of the warfighter, and especially the fallen. In 1971, Johnny Cash, reflecting on a USO trip to Vietnam, sang this about honoring the warfighter while hating the war:

We did our best to let them know that we cared

For every last one of them that’s over there.

Whether we belonged over there or not,

Somebody over here loves them and needs them.[i]

In the same spirit, Dr. Jonathan Shay wrote this in Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character:

Learn the psychological damage that war does, and work to prevent war. There is no contradiction between hating war and honoring the soldier. Learn how war damages the mind and spirit, and work to change those things in military institutions and culture that needlessly create or worsen these injuries.[ii]

For those who think their Christianity excuses them from ministry to warriors, from getting tangled up in the difficulties of war, I remind them that even Jesus ministered to those in the military.[iii] Nothing in our Christianity excuses us from engaging war and serving warfighters, and, in fact, quite the opposite is true in my opinion.

Still, one of the most difficult questions posed to me during my interview to become a chaplain reverberates to this day: “What business does an emerging peace church have endorsing a military chaplain?” And my response still is, “If we truly believe in proclaiming peace, and in promoting Zion, where better should we be than those caught in the midst of war?”

Mirroring the difficult task of proclaiming peace in the midst of war, the Restoration has a nebulous tradition with war. The Book of Mormon might as well be subtitled “Another Testament of Jesus Christ, and War.” If Mormon only published “the hundreth part” of the available records to him,[iv] I have to wonder why so much war? Except, if I accept him as a literal historical figure, I’d have to wonder if war and death had been such a part of his life that he had to record it, mark it. Like a war veteran with PTSD who only sees war images when presented with Rorschach inkblots, all too often Mormon tells the story of Christ and God’s people through war. I find myself falling into the same trap, peace and war becoming so terribly intertwined at times, though I have only seen the hundreth part of what Mormon saw.

In our history as a people, we’ve seen several wars and responded in various ways. The Mormon War was the worst persecution we’ve experienced, and it brought out the worst in us. To avoid its repeat, we formed a militia in Nauvoo, which invited the very thing it sought to dissuade—reminding me of another Johnny Cash song, “Don’t Take your Guns to Town,” or the words of Christ, “live by the sword, die by the sword.”

After the death of Joseph Smith Junior, Brigham Young (from a utilitarian perspective) wisely utilized the Mexican-American War—known as the US Invasion of Mexico, on the other side of the border. Ironically, a decade later, US troops would march on Young’s Zion. For those in the Utah Territory, the Civil War provided some respite from government attention. For the Reorganization, though—which came into being during the Civil War, and lacked the geographical isolation of Young and his Saints—the Civil War was formative to thought and trajectory.

Joseph Smith III was an abolitionist. In his memoirs, he records, “I was not a politician, but I had strong opinions in regard to such subjects as human slavery, and felt it incumbent upon me to fearlessly express my views and to do what I could to help the Nation overcome what I so plainly recognized as an evil.”[v] But the young Prophet-President of the Reorganization, while feeling a patriotic duty to serve in the military and for the cause, was hesitant about war, stating “There were moral issues interwoven, to which we felt it our duty to give careful consideration.”

He states that early members of the Reorganization understood the doctrines of the Restoration to not “warrant the shedding of human blood except it became necessary in defense of our families of ourselves,” and even then “contemplated only as a last resort.” Still, he adds, “[i]n spite of this firm conviction, our spirits stirred deeply to the call of patriotic duty.” Torn between war and peace, ideals and realities, he continues that “[p]rayers for guidance were fervently offered unto the Lord,” and:

When the answer came, it was clear, definite, and unmistakable, and was borne in upon our souls with great distinctiveness. In substance it was as follows: Do not enlist. Enlisting makes your military serve an individual and voluntary action, whereby you might shed blood while in the service. Wait; if drafted, the responsibility is lifted. In such case do not hesitate to take your places in the ranks and to do your full duty as good soldiers and citizens, supporting the government to the best of your powers. In such an event do not shirk any duty the service requires, even should it mean the shedding of human blood, for through the conscription the deed becomes a national sin instead of a person one. The Nation as a whole will have to suffer for its sins, but you will not be held personally under moral obligations in the matter if you do not voluntarily enlist.[vi]

While I appreciate this sentiment, and believe it to be inspired, I still accept that the understanding of Joseph Smith III is clearly represented in this revelation alongside the voice of the Lord. Further, as a non-canonized revelation, I have no qualms in critiquing it. Though a nation might have war sins, these sins are born collectively by individual people, especially by those who do the dirty work. Perhaps it’s true, psychologically, that being drafted and then having to kill another person might assuage moral responsibility; but I suspect that it would intensify the moral injury of having to commit the act, of being forced to do things that you hold to be morally reprehensible. PTSD is the outgrowth especially of moral injury, but also of physical injury, fatigue and wear, and shock and fear—and waiting to be enlisted frees you from none of that. Sin is anything that alienates us from God’s plan of happiness; and we needn’t be the sinner to be alienated from that happiness God would have us enjoy.

War is the epitome of sin.

Personally, I can say that, even as a non-combatant who is surely free of any sins of war, I carry the scars of war regardless of the names at the top of the bill. But more than my little trip to the desert, it is the injured, dead, and traumatized civilians in war zones, though all sinless, who truly bear the sins of war on their bodies and souls. In them we see the face of the suffering Christ.

I would hope that our understanding in Community of Christ on war, sin, and agency has matured over the years—and surely it has, though I think we need to continue to hash out our position on these very issues. Some things never change: We still wrestle with Joseph Smith III’s dilemma, and we still uphold his inspired response, remaining committed to peace. In recent years, Community of Christ has pursued peace in a variety of ways, and continues to emerge as a peace church. We have a long way to go, but I firmly believe that we are on the path.[vii]

I wonder about my fellow veterans in Community of Christ, their views on military service, and on belonging to a peace church. I wonder about the position of the church on military service in the future, as we further explore Zion and what it means to “renounce war and proclaim peace” (D&C 98:16; CofC D&C 95:3d). As one Army chaplain with PTSD recounted in his memoir, “…violence simply leads to more violence,” and “we are poorly equipped as humans to judge who should deserve to die. I hate war.”[viii] And to that I say ‘Amen.’ I believe that the day is coming when we can no longer, in good conscience, support any form of violence; but even more so, actively oppose it, in line with the cross of Christ as a radical rejection of the efficacy of violence. Will we reach a point where we uphold something like Joseph Smith III’s revelation, that military service should be avoided unless drafted? I think it’s quite possible.

Especially on this Memorial Day, my own personal dissonance is a little more punctuated, as someone called to proclaim peace as a member of a war-fighting force. There are no easy answers here, something I know better than most, as I prepare to go and pray for the dead and their loved ones one more time, and all over again.

[i] “Singin’ in Vietnam Talkin’ Blues,” from the Album Man in Black, Columbia Records, 1971

[ii] Jonathan Shay, Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character (Simon & Schuster: 1995), page xxxiii

[iii] Matt. 8:5-13

[iv] Words of Mormon 1:5 (1:8 CofC)

[v] The Memoirs of President Joseph Smith III (Herald House: 1979), page 85

[vi] Ibid, page 90

[vii] On whether or not Community of Christ is truly succeeding at being a peace church beyond just rhetoric, see the exchange between Dr. Matthew Bolton and his father Apostle Andrew Bolton:

http://saintsherald.com/2009/04/30/the-community-of-christ-is-not-a-peace-church/

http://saintsherald.com/2009/05/15/the-community-of-christ-is-becoming-a-peace-church/

[viii] Roger Benimoff, Faith under Fire (Broadway Books, 2010), page 233