Metaphors are an inexact science. But sometimes they can capture feelings and anxieties in a way that scientific language rarely can. Perhaps that is why scriptural texts are filled with metaphoric language: the body of Christ, the stone cut from the mountain, the living waters. In the revelation designated as the “preface” to the Doctrine and Covenants, it is declared that the Church is not only “true”—a description over which many religions have battled—but also that it is “living.” The gospel, the revelation insisted, is a living organism; it is meant to develop and expand, to stumble and recover. A doctrine of continuing revelation is meant to inhibit staid complacency and instill ability for adaptation. “How long can rushing waters remain impure?,” asked another metaphoric passage in Joseph Smith’s revelations, emphasizing the constant need for progress.

According to Thoreau, to be “alive” means, first and foremost, to be “awake.” It entails making conscious decisions about one’s surroundings, one’s talents, and one’s shortcomings, and then being willing to act accordingly. “I went to the woods,” Thoreau declared in the opening pages of Walden Pond, “because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” In an increasingly industrial age, Thoreau feared he was missing the essence of living. Going through the motions, failing to experience the full potential of corporality, would result in dying after never having lived in the first place.

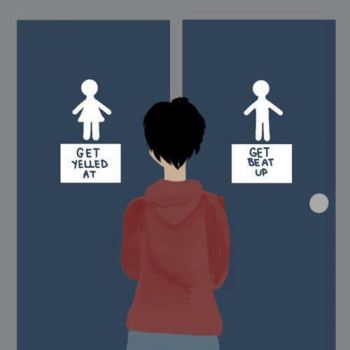

But in an age of corporate personhood, what does it mean for a church to “live”? In common LDS discourse, the metaphor mostly underlines the importance of modern-day prophets and the power of continuing revelation. So be it. But it also introduces vulnerability. To anticipate change implies that change may be necessary. Yet when humans are involved, there is rarely a consensus on the nature, timing, and extent of change. One’s naïve teleology of progress rarely matches another’s. The life-giving ability to adapt with the times often frustrates those who wish sacred things to be timeless.

“To say that there will be a stated time, in the history of this Church, during its imperfections and weaknesses,” the apostle Orson Pratt once declared, “when the organization will be perfect, and that there will be no further extension or addition to the organization, would be a mistake.” Despite the numerous pitfalls, of which Pratt experienced many in his lifetime, the “organization is to go on, step after step, from one degree to another, just as the people increase and grow in the knowledge of the principles and laws of the Kingdom of God, and as their borders shall extend.” The Church, just like the average saint, grows through trial and error, through joy and pain. To halt progression is to be damned.

It seems ironic that a gospel culture never meant to crystalize in form has become so fixated on certainty. Admitting fallibility in the past threatens to underscore fallibility in the present; acknowledging fallibility in the present threatens to undercut hope in the future. Yet anthropomorphizing the Church, and highlighting its living quality, helps one remember that the gospel is always filtered through fallible individuals, not written on stone by the finger of God. God’s work and glory is transmitted through and dependent upon His workers. Mormonism is understood best when it is acknowledged to be an eternal work in progress.

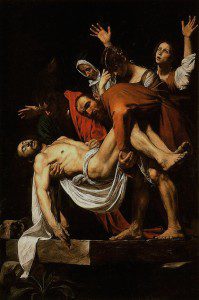

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is living not only because it lives within each one of us, but also because it lives through us. We feel the gospel inhale and exhale, grow and stumble. We feel the joy, and we feel the sorrow, not because we are the appendages to the body, but because we are the body itself. That fact not only makes the expulsion of crucial members from that body so painful, but it also makes commitment to the body’s healing so necessary.

Fortunately, Christ came to redeem all those who live. To be alive implies the necessity to be redeemed. The redemption of Christ sanctifies the Body of Christ, and all living bodies therein. Awakening to our own vulnerability—our personal, communal, and institutional vulnerabilities—is not only the essence of being alive, but also the essence of being Christian.

It is also the essence of being Mormon, for that matter.