Few experiments in religious communalism better exemplified the blending of American industry with religious socialism than did Joseph Smith, Jr. and the Mormons. Despite failed attempts by the Mormons to establish permanent communal societies in Ohio and Missouri, the ethos of religious socialism persisted, and in many ways still persists, within the Latter Day Saint restoration movement. Among the various institutions that sprang from Joseph Smith, Jr.’s innovations, many attempted to maintain the vision of communalism that Smith termed the United Order of Enoch. In 1848, James Strang organized the Order of Enoch in Wisconsin among his followers, as did Lyman Wight in his Zodiac colony in Texas. Sydney Rigdon began organizing his Pittsburgh group communally in 1845; and by 1853, Alpheus Cutler revived the Order of Enoch among his followers which, despite several fits and starts, still remains an important practice within the Church of Jesus Christ (Cutlerites) today.

The focus of this article will be on Mormon communalism following the Civil War years, which includes the largest Latter Day Saint denominations: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) and the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS/Community of Christ). In 1873, LDS president Brigham Young began organizing the United Order of Enoch throughout the Utah territory with over two-hundred communal settlements commissioned at its peak. Although the majority of these societies failed within their first year, a few such as the agrarian Orderville and Kingston colonies showed remarkable sustainability. Peculiar to the second wave of American industrialism were Utah’s urban experiments where communitarian principles combined with factory production, transforming entire congregations into industrial laborers under a system of cooperative manufacturing. While Young suggested he had yearned to reestablish Mormon communalism among the Saints in the Great Basin since their 1847 arrival, its revitalization did not take place until after the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad in 1869 and ensuing Panic of 1873. These events motivated Young to seek insular economic recourse, even going so far as directing his followers to discontinue all business transactions with “Gentiles,” or non-Mormons who had moved into the territory.

Where Young’s communitarian resurgence may have been spurred by outsider encroachment and economic instabilities, the Order of Enoch that began a few years earlier in Dacatur County, Iowa among RLDS adherents received a more guarded introduction. Realizing the hostilities that religious zeal can exact, Joseph Smith III exercised caution with the growth and movements of the church in effort avoid the violence that haunted his family. However, the Mormon principle of gathering was deeply ingrained within the Latter Day Saint worldview and, in their October, 1869 conference, committee reports on desirable locations to establish a colony were given. Despite Smith’s initial reservations, articles were drafted the following year for the Association of the United Order of Enoch as a joint-stock company, and two-hundred fifty acres were obtained in Decatur County, Iowa, beginning a township they named Lamoni.

Section 2 of the articles of the United Order of Enoch stipulates:

The general business and object of this corporation, shall be the associating together of men of capital, and those skilled in labor and mechanics, belonging to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints [later differentiated by adding “Reorganized”], in the States of Iowa and Missouri, and the other states and territories of the Unites States . . . to take cognizance of the wants of worthy, and industrious poor men, who shall apply therefor, and provide them with labor and the means of securing homes and a livelihood.[1]

While Smith permitted the communal venture he did not personally manage its affairs, preferring instead to leave its administration to an eight-member Board of Directors who raised capital through the sale of stock certificates. According to historian Richard P. Howard, over eighty stockholders invested $44,500 (445 shares) into the United Order by the end of 1870. Among these 445 shares, the majority (250) were owned by its eight board members. Among the eight, the top three shareholders – David Dancer, Elijah Banta, and Israel Rogers – also made up the Presiding Bishopric of the church.[2]

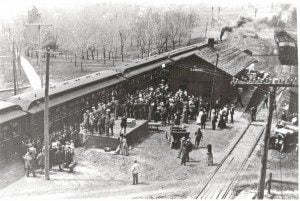

In accordance with their articles, the “industrious poor” were allocated land and provisions enough to sustain their families. The charter was intentionally established for a twenty year time period with the provision that, upon expiration, all assets would be divided equally among joint-stock owners. When Smith paid a visit to the community in 1877, he was impressed with the progress he saw. “We found a changed land to what we visited and rode over some six years ago,” Smith relayed, noting a “busy scene of cheerful farm life.”[3] In the spring of 1879, Order of Enoch officials successfully negotiated with the Iowa legislature for a railroad line, and the first passenger train through Lamoni made its stop on Christmas Day that same year.

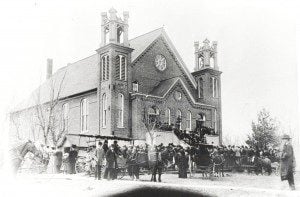

In 1880, Smith ushered in a new era for the thriving society by announcing that RLDS church headquarters were to be moved to Lamoni. The population began to steadily grow from 300 in 1881 to over 1,500 by the turn of the century, with Smith and his family among them. Business flourished along the city’s streets, including numerous general stores, drug stores, banks, hotels, restaurants, and a grain elevator.[4]

In 1890, the United Order of Enoch charter expired. Feeling satisfied that it had run its course and resulted in an economically stable community, the joint-stock company was dissolved and, per arrangement, all assets were divvied up for private ownership. Although sites were now set on Independence, Missouri as the RLDS church headquarter location, enough members and capital remained in Lamoni to build a college. Founded in 1895, Graceland University, which continues to operate as a non-sectarian liberal arts school of about 2,300 students and 150 faculty, stands as a testament to the success of Lamoni’s communal beginnings.

Religious communalism following the Civil War experienced significant changes as the landscape of America rapidly shifted with both industrial and transportation advancements. The successes and failures of Latter Day Saint communal societies in Utah and Iowa illustrate this period of dynamic change. Railroads and manufactured goods began pulling America away from its agrarian handicraft societies towards populous urban centers. In the process, millenarian expectations slowly gave way to pragmatic joint-stock communities which embodied American enterprise in the emerging Progressive Era.

[1] Proposed Constitution of the First United Order of Enoch (February 16, 1870): 126, Community of Christ Archives.

[2] Richard P. Howard, The Church Through the Years, Volume 2: The Reorganization Comes of Age, 1860-1992 (Independence, MO: Herald Publishing House, 1993), 39.

[3] Roger D. Launius, Joseph Smith III: Pragmatic Prophet (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 181.

[4] Ibid., 183.

Special thanks to Ardis E. Parshall for bringing the Kingston Order in Utah to my attention.