I was not entirely surprised last week when I faced blowback from the Muslim community on social media regarding my suggestion to have congregational prayers on Saturdays (it is almost universally held on Fridays). Although my suggestion was mainly for Muslims in the West who do not have much time on Fridays, the blowback came from my country of origin, Malaysia where I am known as a ‘liberal thinker’, the honorific ‘thinker’ being considerably diminished by the pejorative ‘liberal’. Some claimed that I wanted to abolish Friday prayers, others even claimed I am organizer working with the Malaysian people’s heroes, the Bersih movement who call for free and fair elections. Perhaps the greatest irony of this situation is that among many Sunni translations themselves, ‘yawm al-jumu’ah’ is translated as ‘day of congregation’ instead of Friday!

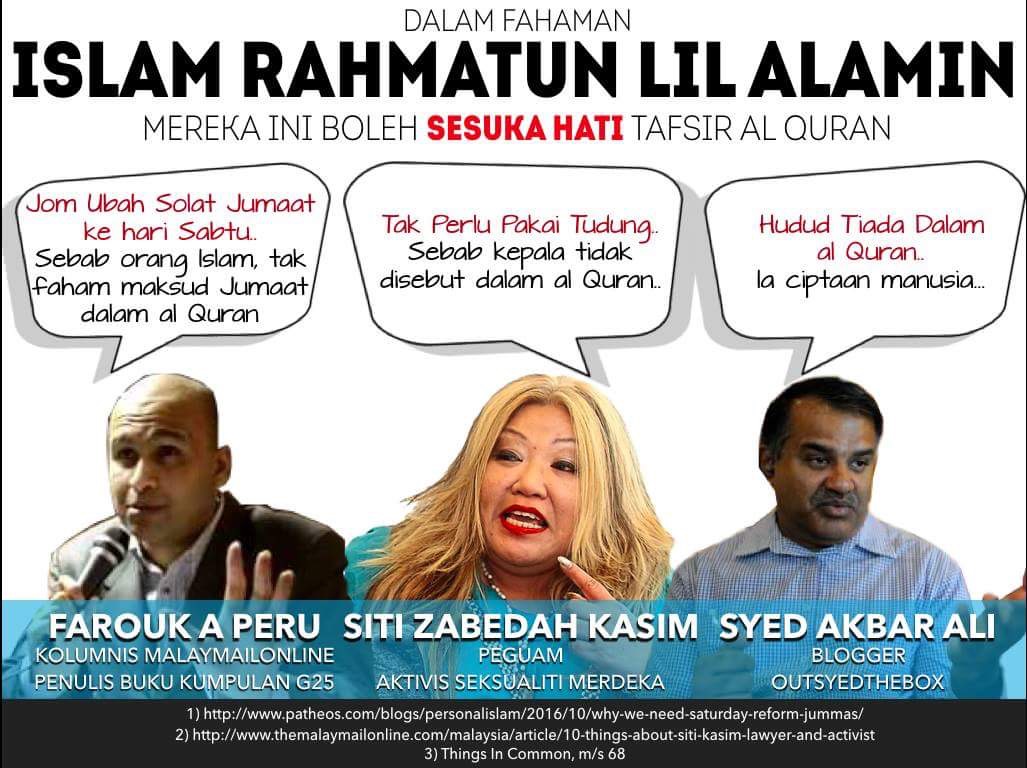

Below are the memes circulating about me. They are either taking liberties with the truth or outright lies!

This episode has made me think about Islamic rituals – the prayers, fasting, hajj and others. Muslims are very attached to the rituals. Indeed, from an early age, religious Muslims are taught by their parents that these rituals are what makes us Muslim. They are sent to religious schools where at least the bulk, if not the entirety, of religious education is centred around teaching these rituals and the correct way to perform them.

I totally understand and empathize with this attachment. I am a product of it myself.

I feel our current stagnation should prompt us to ask the question: are these rituals the point or the means to a particular end? Did Allah command us to perform rituals for the sake of it? Or in His infinite wisdom, did He command human beings to perform religious rituals as a preparation towards a higher goal – perhaps Allah Himself?

As always, the Quran does not leave us hanging. Its author, knower of the unseen and witnessed (‘alim al-ghaybi wa ash-shahaadah – Quran 6/73), knows full well that human beings would ask about the purpose of ‘salah’, for example. We are told, for example, the purpose of salah is to remember or vivify Allah (Chapter 20, Verse 14). We are also told that salah, along with the rehearsal of verses from the book would eliminate lewdness and unrecognised acts (29/45). Furthermore, we are told that people are generally very fickle and unfocussed except those who are in salah (70/19-22).

This shows that salah is not an end in itself. Whilst in Traditional Islam, we are told that we win spiritual points for keeping up our prayers – the fajr or dawn prayers being the most lucrative especially if performed in congregation – such a thing is not mentioned at all. Rather, we can see the effect of the salah which is to bring us closer to Allah. This is how we should view rituals, as a variety of means to an end – divine closeness.

And what of other rituals? Lets take ‘sawm’ or the fast or example. The obligatory fast is instructed during the Traditional month of Ramadhan. However, the dawn to dusk fasting period is lengthened due to longer days. In the UK this year, we fasted twenty hours instead of the fourteen hours in equatorial countries. And what if there is no dusk at all for months? Shall we then starve for days until death? Fortunately, Muslims have rethought their fasting obligation and have come up with different solutions. Happily in this case, Muslims have put God before the ritual. This is in keeping with the spirit of the Quran which states fasting is for God consciousness and His magnification, leading ultimately to His closeness (2/183-186).

The same cannot be said about the stoning act during hajj. This ritual, in which the Hajj pilgrims walk up to three pillars which symbolize the devil and proceed to stone them, has the problem of overcrowding each year. In fact, tragic deaths have occurred due to overcrowding. People have been trampled to death. Yet we have not heard of a global fatwa agreement that this act can be spread out across a number of days. People’s lives are not worth the risk of one’s credibility as a fatwa maker, it seems. In this case, the ritual has become more important than the goal. This is incongruous with my understanding of the Quranic hajj which is gathering for all people to witness the benefits of the islamic system (22/25-28).

If we place my Saturday Jummah in the above context, does it really seem all that controversial? Is it really so offensive to ask to congregate on a day in which we have actually have time to get closer to Allah? We could really make a whole day of it. Fast or eat light, do some social work, discuss the Quran and wider social issues, even attend a course as well as pray and listen to a sermon, ending the day with a sumptious iftaar of thankfulness. It could truly be a rewarding experience – if only we had more time.

Why is the day itself more important than the actual activities we can perform given a longer period? These are things we need to think about. After all, we are here to worship Allah, not the religion itself.