Remind me to send Jesse Ellison a thank-you card. Without the benefit of her insight, I would never have realized that I’m not a conservative.

Conservative circles, she says, “regularly deny that date rape exists.” And Ellison writes for The Daily Beast, which means she basically knows everything there is to know about conservatism. Therefore, I must not be a conservative.

Because I believe that date rape exists. And I believe that what Bristol Palin describes in her memoir Not Afraid of Life — a night of alcohol-addled coupling in a tent in the Alaska wilderness that she did not even remember in the morning — qualifies as sexual assault. Perhaps that’s just because I’m the father of a daughter, and I can imagine the volcanic rage I would feel toward any young man who plied my daughter with drinks until she was effectively half-conscious and then took her virginity. Or perhaps that’s because I’m, you know, a conservative, who believes in abstinence until marriage, in the sacredness of the sexual bond, and in treating women with old-fashioned chivalrous respect.

This is one of the bombshells of the book, that Bristol began her sexual relationship with Levi with what many reasonable people would describe as sexual assault. Here are the relevant parts of the story. Bristol is in her middle teens; the exact age is not given in the parts I’ve read, but the timeline works out to around 15 years of age. She tells her mother she’s spending the night at a friend’s house, but goes instead with Levi and friends to drink and camp out for the night. She drinks a lot of wine coolers. “Levi kept replacing my empty bottles from his large stash.” The wine coolers tasted sweet, and — not much accustomed to drinking — Bristol didn’t realize how much alcohol she was ingesting. Soon she passed from the “happy buzz” into the “dark abyss of drunkenness.”

One moment, she’s laughing in a chair beside the fire with her friends. The next thing she remembers, she awakes in the morning in a cold tent with a splitting headache. Levi’s laughing with a male friend outside. Bristol summons her friend to the tent.

Within seconds, [the friend] unzipped the tent and poked her head in. “Are you okay?”

“What happened?” I whispered.

“You don’t know?”…[T]he next sentence that came out of my friend’s mouth hit me like a punch in the stomach. “You definitely had sex with Levi.”

Suddenly, I wondered why it was called ‘losing your virginity,’ because it felt more like it had been stolen.

It goes without saying, and yet must be said, that although the story sounds plausible enough (this sort of thing happens all the time), I cannot say for certain that Bristol is telling the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Levi claims — as any young man would, whether it was true or not — to have thought it was what she wanted. Of course, Levi has his own memoir hitting bookshelves soon, but credibility at this point, given the things he has said and retracted and un-retracted in public, is virtually nil. Still, I cannot confirm the veracity of this account. No one can, in part because it depends on private communications between Bristol and Levi.

But the point is not to convict Levi. The point is: Does this kind of scenario amount to sexual assault? Several thoughts on this and other questions raised by the book:

FIRST: Anyone who excuses the kind of behavior alleged of Levi should be ashamed of himself (or herself). There is no such thing as meaningful consent from a drunken 15-year-old girl, not to mention one so drunk that she doesn’t even remember the encounter in the morning. No. Such. Thing. We need to do better as a society at protecting our daughters. We need to demand more of our young men. The age-old strategy of drowning a girl in wine or booze until she no longer knows her up from down, her right from wrong, so the young man can have his conquest while her defenses are down, is immoral, shameful and criminal.

It’s not uncommon to hear of cases where a young woman is barely coherent, barely even awake (if awake at all), when a young man at a booze-sodden party takes advantage of her. Then the young woman wakes up feeling broken and violated, robbed and ashamed. Something she had held precious — whether her virginity or just her God-given right of freedom — was taken from her.

In this case, if the story is true, Bristol had been clear on her intention to abstain from sexual intercourse until marriage. Who knows how coherent or clear she seemed? Who knows whether she might have said she wanted to have sex? But the point is: it’s what she said before she got drunk that matters. We need to communicate this to our sons: if the woman said NO before she was inebriated, what she says post-inebriation does not remotely matter.

But I wouldn’t hold your breath waiting for the National Organization for Women to come to Bristol’s defense.

SECOND: the story itself is a parent’s nightmare, but more destructive still was what followed the drunken encounter that night. As Bristol says, she should have admitted her mistake to her parents (and God) and cut Levi loose. Instead, feeling like damaged goods, like the only way to redeem the situation was to stay together and get married, to make him into the kind of man she believed he could be, she ignored Levi’s obvious faults and stuck around. It was this decision that led to a longer relationship and ultimately to her pregnancy at 17 (Tripp was born shortly after she turned 18).

As important as it is to communicate the power and sacredness of the sexual bond to our children, it’s just as important to communicate that they can and should come to us when they fall. Bristol, it seems, did not have a strong enough sense of herself to let Levi go. Presumably her parents, if they had known what Levi had done, would have intervened and ended the relationship. From Bristol’s perspective, once her virginity was gone anyway, determined as she was that they should marry, what was the harm in continuing the sexual relationship? Well, as it turned out, the harm was pretty severe. Things might have been different if she were equipped and encouraged to respond in the right way to that first error.

THIRD: The way in which the book hit the headlines was typical of the anti-Palin circus. The publisher, William Morrow, was protecting the book with extraordinary care. They weren’t given copies to anyone. Yet someone sold a stolen copy to the Associated Press, and all kinds of American media outlets began blaring the headlines — copying what they saw written elsewhere — that this was some kind of catty, spiteful, whiny, Mean-Girls-esque “burn book” getting back at Levi and McCain and anyone else she didn’t like. And of course now the stay-classy liberal blogosphere is claiming that Bristol made up the story in the Introduction in order to blame Levi for her sexual indiscretions. Yet that’s not the way the book comes across at all. Bristol is open about her mistakes, and yet it’s a redemptive tale in which Bristol emerges from that dark valley to find meaning, purpose and grace. Don’t believe the mischaracterization of the book from the anti-Palinariat.

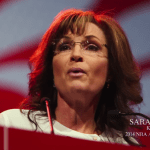

Personally, I’m glad Bristol told her story. It’s an important one for young people, who find themselves reflected in Bristol in much the same way so many Tea Partiers find themselves reflected in her mother. Bristol’s story illustrates how a series of small, seemingly harmless decisions can lead you straight into the swamps. Yet it also illustrates how the painful and the ugly things in life can, through grace, be transformed into meaning and beauty. It’s an important story for parents to hear, as they try to navigate the treacherous shoals of raising children in the twenty-first century. It must have been painful at points for Sarah and Todd to read; and I would think in particular that Todd would have wanted Bristol to have the gumption to leave Levi after he got her drunk and took her virginity. And it’s also important for America as a whole to get a clearer sense on what it means by “consent,” especially when it comes to sex between minors and when alcohol’s involved. Young people should know in no uncertain terms that there is no such thing as meaningful consent when it comes to drunken teenagers.

And for the record: conservatives do not deny that date rape exists. In spite of what Jesse Ellison might say.