Note: This is my second post in response to Nadiya Takolia’s article in the Guardian. Read the first one here.

Today I want to discuss two problems with Takolia’s narrative about the hijab as a feminist, empowering device. The first has already been pointed out, but I want to reiterate it because it’s important:

Takolia justifies her decision as follows:

There is much misunderstanding about how women relate to their hijab. Some, of course, choose the headcover for religious reasons, others for culture or even fashion. But in a society where a woman’s value seems focused on her sexual charms, some wear it explicitly as a feminist statement asserting an alternative mode of female empowerment. Politics, not religion, is the motivator here. I am one of these women. … It makes many of us feel like a pawn in society’s beauty game – ensuring that gloss in my hair, the glow in my face and trying to attain that (non-existent) perfect figure. … Subconsciously, I tried to avoid these demands – wearing a hat to fix a bad-hair day, sunglasses and specs to disguise a lack of makeup, baggy clothes to disguise my figure. It was an endless and tiresome effort to please everyone else.

I do not believe that the hair in itself is that important; this is not about protection from men’s lusts. It is me telling the world that my femininity is not available for public consumption.

In other words, she was tired of feeling like public property. Many Christian women say the same thing:

Please, dear sister in the LORD, don’t entice others or provoke others to openly view the gift you are to reserve only for your own husband.

My mother told me often about the relief she felt wearing loose dresses and long prairie skirts. She no longer caught men leering. She no longer worried about gaining weight. She no longer had to maintain a haircut. It’s true: society does put pressure on women to perform hours and hours of work to achieve “presentability.” The effect is to ensure that women feel scrutinized for everything, that their bodies are being imaginatively torn apart and dissected piece by piece. No one is really immune to it, either. Even after working through the majority of my body image issues, I was sent into a spiral for a week this month after accidentally stumbling upon an advertisement for plastic surgery for a “problem” that I never thought existed. Suddenly I couldn’t “unsee” the problem when I looked in the mirror. For a week! We do live in a society saturated with near-nude female images that are digitally manipulated, even mutilated, to match an increasingly alien ideal:

Please note that I’m not arguing that skinny girls aren’t “real women.” I’m rather slim myself. The woman pictured here, from the Victoria’s Secret website, does not actually exist. She’s a photoshop creation. Did you know that photoshop artists regularly slice off women’s sides and thighs? The right side (from the viewer’s point of view) and both thighs have been cut and replaced with the ocean backdrop. The woman’s arms are positioned so far back that she looks skeletal. Her torso appears to have been stretched to look longer. The shadow between her breasts? Airbrushed. Not real. You can do almost anything with photoshop, including smoothing out the hip bones that would be extremely obvious in a woman this thin. There is no part of this woman’s body that we can actually see. What we see is the work of an underpaid artist. The woman is just the canvas.

That’s the Western beauty standard. That’s what Takolia thinks she’s escaping by wearing the hijab. But she isn’t.

The Western beauty standard objectifies women by erasing them. An attractive woman is one who doesn’t take up space, whose body does not betray the signs of life: bone structure, fat storage, musculature, pores. All of those things are good things – they keep you alive! Erasing them means covering up women – actual, living, human women – with a thin veneer of “beauty” that must be studiously maintained.

Whenever a woman’s unaltered body becomes visible, it is told to cover up. Cellulite? Cover up. Untanned flesh? Cover it up, you look naked. A soft belly? Cover that up until you go to the gym. Leg hair? Cover it or shave it – your choice. Western culture does not, as Takolia argues, tell all women to expose themselves for men. It tells that to women who appear closest to the digitally created stock image woman that it calls beautiful. If a woman dares to own her body in public without apology, without shaving or plucking or waxing, without seeking out “flattering” outfits or concealing her less alluring features, she catches hell for it immediately. This takes the form of fat-shaming, slut-shaming, and general verbal abuse. Even my patriarchal male friends, who ostensibly believed that women should cover up to conceal their attractiveness, would make noises of disgust at heavier women in shorts, saying, “I don’t want to see that.” They said little about the women they did want to see.

Religious modesty also objectifies women by erasing them. The hijab feels liberating to Takolia because it enables her to forgo the effort it takes to maintain artificial beauty. That does not at all mean she isn’t participating in the system. She’s just reinforcing it. She has decided that, since she is tired of conforming to artificial beauty standards, she’s just going to hide. What she’s doing is apologizing for her body, for its failure to live up to an ideal of attractiveness.

The first day I stepped out in a hijab, I took a deep breath and decided my attitude would be “I don’t give a damn about what you think”. The reaction was mixed. One friend joked that I was officially a “fundamentalist”. Extended family showered me with graces of “mashallah”, perhaps under the impression that I was now more devout. Some, to my surprise (and joy), didn’t bat an eyelid. I was grateful because, ultimately, I firmly believe that a woman’s dress should not determine how others treat, judge or respect her.

I, too, learned as a young woman to step outside thinking, “I don’t give a damn about what you think.” But I wasn’t wearing a hijab. I was at the beach, wearing a bikini. I had decided that ultimately, I firmly believe that a woman’s dress should not determine how others treat, judge or respect her. How can you go from caving in to the artificial Western beauty standard, which says you should either work to be attractive or hide yourself from male consumption, to claiming that a woman’s dress shouldn’t influence how others treat her? I don’t get it. If you really believe that, why do you need the hijab? If you truly don’t care what others think, why do you find it necessary to obscure their judgment with a piece of cloth?

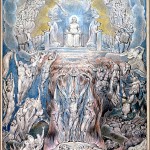

I think Takolia has stopped one step short of truly grasping the power of the ideal beauty standard. The best illustration is this:

This is not about protection from men’s lusts, she writes. It is me telling the world that my femininity is not available for public consumption.

This is where the Christian quotation above becomes relevant. Christian modesty (and Islamic modesty – not the “feminist” kind Takolia advocates) holds that a woman’s sexual allure belongs to her husband alone. It holds that appearing beautiful in public deprives your husband of something. It says that by seeing you, other men take something away from him. Takolia’s rationale is the same, only perhaps gender-neutral (“public consumption” suggests she doesn’t want women judging her, either). Still, though, her assumption is that a woman’s body in public is somehow on offer to be “consumed.” That one appreciates a female body the same way one appreciates a $5 latte – by consuming it, indulging in it. This is objectification.

How about imagining a world in which women’s bodies aren’t consumable goods? Where we don’t have to alter or hide ourselves to appeal to or disappear from male observation? How about imagining a world where women’s bodies are seen the way men’s are – as features of a person?

Finally, let’s try to stop treating “women” as a monolithic category. Women’s bodies are inscribed with different meanings, based on their race, class, sexual orientation and identity, and age. To claim that Western culture demands that all women expose themselves for men is ignoring the way that the same culture says your beauty declines from age 18 and expires when you turn 35, that categorizes certain clothes as “trashy” and others “tasteful,” that criticizes overweight women for daring to put on small clothes in the summer, that demands different things of white women than black women, that more quickly demonizes women of color for their curves, that behaves as though white women’s hips and hair are “default” and women of color are deviations that must be catered to separately. Pat solutions like the hijab and prairie skirt assume that the wearer is a 20-something skinny woman with narrow hips and a concealable bust, and do nothing to address the broader problem of women’s bodies being categorized and dissected in search of meaning.

Next, I’ll talk about the problematic language of “choice” that Takolia uses in her article, especially a choice as fraught with meaning as a secular woman wearing the hijab.