On an early autumn day, when I was about five years old, that’s when I became a wanderer.

On an early autumn day, when I was about five years old, that’s when I became a wanderer.

That was over sixty years ago, now. What happened that day was not a revelation or even a beginning, but the beginning of the beginning; which could have turned out very differently at any number of times along the path of my life. But in retrospect, that was the day.

Welcome to “Pilgrim Life,” an account of my wandering through life, something that only became a pilgrim life well over half way along, when a chance reading of an article about Hadrian’s Wall said you could actually hike it from North to Irish Sea. Without even thinking about it I knew I had to do it. For someone like me, who has a master’s in rumination and a doctorate in overthinking, such moments are very rare.

So I did it, and it was utterly the right thing to do. The pollen released when I was five found the pistil and began to grow. I spent a week trudging through English pastures, getting caked with manure and soaked with rain. And feeling more at peace than I had ever felt.

Since then I have made seven conscious pilgrim journeys on five continents.

Some were treks through desert and forest and mountains, walking 10-20 miles a day almost totally alone. Some were journeys to cities and sites of historic meaning and power that involved trains and planes and automobiles.

I began to realize that my travels before were embryonic pilgrimages, each hoping to capture something of that first time. Which makes that day the perfect place to begin this journal.

… We were out for a drive in rural Maryland, somewhere northwest of Silver Spring where we lived. This was in the day when going for a drive was something you did for pleasure.

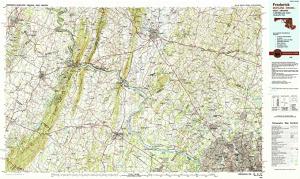

Essential to this story is a map. My father loved maps, collected them, consulted them, inhaled their composite knowledge scribed in lines and numbers and letters. He thrilled to the swirl of topographic elevations, brown and green, faint and dark, Hokusai waves created by surveyors using exotic objects called Adilades and Theodolites. He rode shotgun while mom drove so he could navigate and correlate, delighting to match symbol with object.

Essential to this story is a map. My father loved maps, collected them, consulted them, inhaled their composite knowledge scribed in lines and numbers and letters. He thrilled to the swirl of topographic elevations, brown and green, faint and dark, Hokusai waves created by surveyors using exotic objects called Adilades and Theodolites. He rode shotgun while mom drove so he could navigate and correlate, delighting to match symbol with object.

We were heading for some historic spot, off the road, and therefore all the more alluring. My brother and sister and I are in the back seat of our  Willys Aero Eagle two door, which meant you had to push the back of the front seat forward to get in. We three sat in a row, my baby sister in the middle in an early baby seat that simply perched on the bench, there being no seat belts then.

Willys Aero Eagle two door, which meant you had to push the back of the front seat forward to get in. We three sat in a row, my baby sister in the middle in an early baby seat that simply perched on the bench, there being no seat belts then.

“Turn here,” dad said with his glasses in his teeth, and we were now on a dirt road. Bumping along, for a while he added, “There’s a bridge up ahead according to the map.”

Only there wasn’t.

We got to the little river, more of a brook, and there was no evidence of a bridge, just ruts that led into the water. There was a bridge on the map. Dad showed mom. Sure enough there was a symbol, but no bridge. Dad pored over the map again. How could it be wrong?

Stopping at the edge. Dad got out and took off his shoes and socks, venturing into the brook to see how deep it was. It came half way up his shins.

“We can drive across,” he said.

Only we couldn’t. Mom cautiously began to drive across, after having all three of us get out, brother and I wading in bare feet and sister in dad’s arms. We stood on the far bank as mom drove slowly into the water. She got half way across and stopped. The wheels turned but instead of moving forward the car sank it. Wet sand is not a good surface for driving.

Dad coached mom in the winter method of auto extraction: race forward a few inches, slide back, then quickly slip into reverse to capitalize on the momentum. No good. Soon they realized this would only sink the car deeper and that would let water into the car itself.

Our only choice was to abandon the car and walk back to the main road, which was hardly a major road. I suspect it was less than a mile, but to my five year old legs it was long, and longer still for my three year old brother who was carried for a while by dad. Mom carried sister the whole way. It was not a pleasant stroll. We did reach the main road, of course, not long before sunset. I remember dad’s face, calmly figuring out what to do, and mom’s face alternating between worry about us and anger at my dad for getting us into the fix.

“… In that Empire, the Art of Cartography reached such perfection that the map of a single province occupied a whole city, and the map of the empire a whole province. In the course of time, these disproportionate maps were found wanting, and the Colleges of Cartographers elevated a map of the empire that was of the same scale as the empire and coincided with it point for point….”

So writes Jorge Luis Borges in his short story, “Del rigor en la ciencia.” When I read it, that drive came to mind. Dear dad, trusting the map, led us all astray. Maps are not the world, it turns out. And when I was in Geneva Switzerland forty some years later, that story is what sent me to the Cimetière des Rois to find his grave.