As usual, I’m really looking forward to Lent. I think it’s because Lent is essentially the basic expression of my personality. Some people are stuck in Christmas and tinsel, others rush around trying to self identify with Easter, but for me, by the time I get to Lent, and then to Holy Week, it’s like I can finally take a real breath after trying to hold it for nearly a whole year.

And that with rarely ever giving anything up or taking anything on.

Lent, as I see it, is a brief bright moment to experience the Christian life as it really is.

But first there needs to be a distinction between life in the world and the life of the Christian. In the world it is never Lent. It is never time to feel bad about who you are and the way the world is. Instead, it is mostly always Christmas and never winter. It is always time to indulge yourself and express yourself, to have whatever you want the moment you discover you want it. In fact, there’s also probably an actual fat man leering at you from around the corner telling you deserve to be happy. This happiness includes buying and giving yourself presents.

When you add Jesus in to Christmas you immediately start getting sad songs about baby Jesus looking forward to the sharp nails that are going to be hammered into him later when he’s all grown up. Which proves my point. Wherever you have Jesus, you also have a hefty dose of Lent.

The Christian life is Lent, or Lenten if you prefer. Admitting this is the first step to being happy.

How is this so? Well, for most of us, life is really long. Too long it can seem like. Day after day you do the same thing. You wake up, you put your tent in order (or you should, so that if you don’t you feel guilty, or should feel guilty, or feel guilty for not feeling guilty), you strap on your sandals and jiggle around in your clothes trying to get comfortable in stuff that will never be comfortable, you suck down your morning gruel and peak out of you tent flap to see how much dust is blowing around. You do this Every Day. And in the evening, Every Evening, you stagger back through the door and fling all the stuff down and collapse into bed, not wanting to bother to blow out the ashy candle. In between you do all the same things every day. You have to eat stuff, and talk to people, and shuffle papers or wipe up children. You have to check your email and try not to give in to a cloying anxiety that is leering at you, like Santa, from around every corner–illness, bills, the bad conversation you had three days ago, your boss, your children getting beat up in school, the fact that you homeschool and there’s no way to really succeed at any one task, your project coming up–it could be anything, often it’s everything all at once.

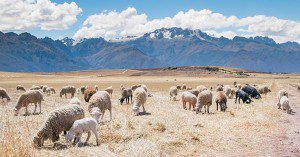

Life isn’t a highway, it’s a desert, a wandering around in a tight circle of anxious and idolatrous disappointment and fear. Every now and then you peak your head over the top of your tent to squint at the mountain. You get swept away for a second in an awestruck fleeting transcendence that you always glance back towards and long for again, but the more you think about it the more you will never get it back.

The desert permeates everything. The grit and the sand are everywhere, like leaven. Just when you think you get them all out, you realize they are airborne, and, in the case of the leaven, basically invisible. You can’t win. You can’t not sin. You just have to keep waking up and going to bed day after day after day.

Does it feel too bleak? The reason I love Lent is because this is the way life is, but we’re not supposed to really feel it. And when we do feel it, we think there’s something wrong. Indeed, rather than meekly accepting the desert of this mortal, sinful life, we are always rushing headlong to the promised land, long long before we’re suppowed to go there, and usually, I think, with technology. The dishwasher, the washing machine, the car, the phone–every promise of movement is just an alluring call to pass over the wilderness and reach happiness before you’re allowed to.

That’s why it’s a breath in my spiritual lungs when we finally get here every year. For a few short weeks the church admits to me that this is really how it is. But this admission isn’t a hopeless one, a caving in, a capitulation. It is hopeful. It is full of comfortable words. ‘Look at the desert,’ the scripture admonishes Sunday by Sunday. ‘It’s not even that you’re in the desert, it’s that the desert is in you. You are stuck and miserable and unhappy. Death is your lot. Sin is your bread.’ You sit in your pew and look at your bread and your disappointment and can only nod. It’s the way things are. And if that was all, you would deserve your clinical depression. It’s not though.

Because Christmas isn’t about presents, and Lent isn’t about despair. Both are about Jesus. The futility of getting up and toiling and going to bed and doing it all again the next day is caught up with the leaven and the dust and nailed to the one who came down the mountain to be with you. The promised land isn’t actually that far off. You have been brought near to it by the blood of Jesus. You can both stand and gaze at it, helplessly, and sit down at the table of mercy and feed on it now. Because it’s Jesus. And Easter is just around the corner.