I should be packing my suitcase and cleaning my house, but indulge me as I first pause for a lamentation. You can read this depressing thing and then this one, and then mutter to yourself, “What could possibly go wrong.” The men hate the women, and the women hate the men. I mean, I think we’ve unlocked civilizational utopia, that’s what I think.

Anyway, I bring them up, those pieces, because I just finished What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories by Laura Shapiro, about which I have raved to every passer-by. Seriously, I love this book so much I’m going to buy myself an actual copy to keep. Shapiro—although I have a strong inclination to call her Laura because, when she told her own food story at the end, I just wanted to sit at her kitchen table and eat all her pakoras—writes about Dorothy Wordsworth, Rosa Lewis, Eleanor Roosevelt, Eva Braun, Barbara Pym, and Helen Gurley Brown. The chapter on Pym, of course, was the best one, the most life-giving, the most satisfying, but all the chapters together composed a literary feast. I saved them up to listen to when I was in my own kitchen, mincing an onion, stooped over the children’s favorite—white fish in a creamy béchamel—picking little leaves of thyme off the stem one at a time. When a child would interrupt me to ask how long till lunch I would shout, “Soon,” and, “Leave me alone.”

All that to say, Helen Gurley Brown…egads. She might as well be a gruesome female replica of Hugh Hefner. The two of them, entombed in perversity, fashioning each a soul-crushing media empire in his and her own crooked image, must have formed, in the American mind, some unholy, ungodly female destroying alliance. Did they ever meet, I wonder? Brown thought of herself as a feminist—I went and read a smattering of articles published at her death. But so did Hefner claim to be “pro-woman.” Women should be allowed to love men, they both simpered. Which is technically true, I suppose, but not in such a way that the very body of the woman is so consummately contorted that she ceases to be human at all.

Brown did not eat food. Being thin, to the point of anorexia, was the grandest ideal to which daily she aspired. She wanted to be thin no matter the cost. Women should be thin, she insisted. And men who didn’t love thin women weren’t worth anyone’s time or attention.

I listened to Shapiro quote whole passages from Sex and the Single Girl, recipes from her foray into cookbooks, and articles from Cosmo. The narrating voice rung in my ears as I hunched, insecure and heartbroken, over the occasional abandoned tray of cold, dead tater-tots. “I have to eat these,” I said to myself, “for the sake of all women everywhere.”

How strange it is that the most ordinary thing from the dawn of time—being a human person who eats, breathes, talks, clothes the body, lies down to sleep, wakes up to work—should be so perilous, so desolating, that the one half should marshal every available resource to hate, ruin, and destroy the other half. Strange, perhaps, though ancient—that first bite in the garden, that very first taste. The juice ran down the arm, the sweet lingered in the mouth, and the two were divided from each other forever. The bread of their common life is to loathe, control, blame, and corrupt the person across the table, on the other side of the bar, on the touching point of a finger swiping right or swiping left.

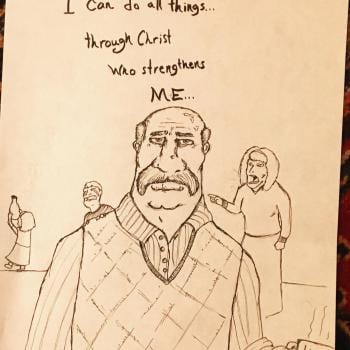

Though there is another kind of bread. A communion that is rejoicingly lifted up, broken apart, divided out into so many palms, tasted by so many stooped and troubled men and women. It may feel dry and bland on the tongue. But it’s the only remedy, the only way to regain the breath, the satisfaction, the other person’s new loving eye.

Oops, it’s only Thursday, but you should still go to church.