Here we are at another Lenten Friday. I think I can rustle up some links to stuff that will be far more scintillating than trying to think of anything new.

One

This Lent hasn’t been a total failure so far, though I haven’t blogged in the way that I intended, as in, I kept not blogging at all. BUT, the one good post I managed I have reworked and you can read it here:

“I invite you, therefore, in the name of the Church, to the observance of a holy Lent,” the pastor paused for breath and stretched out his hands to the congregation, trying by the power of his will to disbar the sleep from their eyes, for it was only seven in the morning, and a miracle that any of them were there at the appointed time. His voice called across the empty pews, “by self-examination and repentance; by prayer, fasting, and almsgiving; and by reading and meditating on God’s holy Word.”1 The assembled ten people, bilious from the carb-laden stupor of previous evening’s Shrove Tuesday Pancake Supper, wrestled their wandering minds to the liturgical mat and began to confess their sins.

It is an ancient practice — the observation of Lent — and one that for many, especially in the apocalypse of COVID-19, is falling by the way. It is becoming a vestigial yet beautiful anachronism for which formerly religious people feel nostalgia, without being able to remember why they obeyed when the church called for their penitent attention.

One such person, Margaret Renkl, writing in the New York Times, found that when in-person services resumed, she had no more desire to go. When, suddenly, Lent loomed up on the horizon, she was forced to rethink the cultural and spiritual rhythms that had given her life some sort of, if not theological, at least practical structure. From the sanctuary of her home, she grappled with the call that I myself heard from the pew, the observation of a Holy Lent, and the smear of ash on my forehead. “Performing this ancient ritual,” writes Renkle, “he will murmur, ‘Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.’ The priest will say these words on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, but he will not be saying these words to me.”2

Her growing disaffection for the Church, particularly the Roman Catholic Church’s stance on women, was precipitated into full blown alienation in the time of COVID-19. But the deeper problem, I think, is that Renkle ceased to believe in the God whom Christians worship. She puts it this way:

I have had a troubled relationship with the church of my childhood since childhood itself, when I learned in Catholic school that I would never be allowed to become a priest. For decades, nevertheless, the gifts of my faith outweighed the pronouncements of the institutional church that I found alienating or enraging. Human institutions are inherently flawed, and I have always loved the rituals that linked me across time to so many others facing fear and loneliness and pain, to so many others finding solace in their faith. Then the pandemic quarantines left me unchurched through no choice of my own, and the death of our last parent, for whom there would only ever be one Church, left my husband and me free to make our own choices about where to worship.3

There has been a great sifting, that’s true. If you were a person who merely attended a church before the pandemic, the numbers are showing that you didn’t feel like you needed to return when in-person worship resumed.4 Rather, it was the people who sat in front of their wretched screens for several months, frustrated out of their wits, who rushed back to the pews as soon as they were able. These people weren’t church “attenders,” they were members, they belonged — not by some happenstance, but because they had worked for many years to wedge themselves into the lives of other people. Or rather, God incorporated them into the mystical Body of His Son. It was painful and hard, but it happened, and so on the other side of lockdown, there wasn’t any question, they went rushing back.

And this is the key to approaching any particular season in the church, whether a penitential one, like Lent, or a celebratory one, like Easter. If the observance is approached as an individual making a personal choice, the meaning and purpose of the church’s invitation becomes obscured and may even cause distress. For the nominal church attender, like Renkle, when Lent rolls around, questions of religion and faith, however unbidden, surge to the fore: “Isn’t the promise of immortality what Lent prepares us for? How will I make ready, now that I am without a church? What rituals will I observe, now that the stations of the cross no longer belong to me?”5 The “promise of immortality” is rather a vague way of referring to the moment that we all will face — death. How will we each meet it as we go down to the dust? Can some kind of ritual, divorced from meaning and community, make the bitter pill easier to swallow? Read the rest here!

And if you missed the podcast I did with Melanie, give it a listen!

Two

Ralinda, Liza, and I weighed in on what it means to be a woman. Pretty sure you won’t want to miss it!

Three

This book that I love so much is coming out today, if you want to go get a copy. And this one that I contributed to is coming out soon if you also want to go get a copy. It’s almost Easter, you might want to start buying yourself presents now.

Four

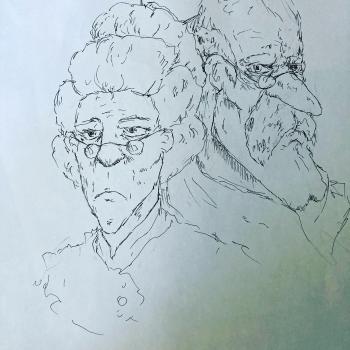

Appropos of nothing I’ve mentioned so far, I don’t know who made this picture but I love it so much I would even buy it in poster form:

Five

And finally, this is the winner of the internet for all time and eternity. Seriously, watch it to the end:

And now I will go along to do all the things. Have whatever kind of day suits you best!

Photo by Sincerely Media on Unsplash