Touched a nerve yesterday, I think, with my brief rant about the moralizing nature of so many books. Amy Marie commented, most astutely, that the Bible and Plutarch, ‘are suppose to be the best books for no moralizing…Just black and white facts.’ Not that I’ve read Plutarch, but I’ve often felt that about the Bible, and one reason I’ve never really doubted that it’s all true. The bland record of the hideous sins of its ‘heroes‘ is most extraordinary. The fact that those ugly things were allowed to remain, that God preserved the text when surely every sane man would have had it destroyed, is miraculous.

The trouble is is that as you’re reading along through the Bible, especially through the history sections, you don’t get very many indications of ‘and this was very bad, this person is the bad person in the story, get it? Hey, hey. Do you understand who the villain is here!’ That alone I think is one of the reasons why preachers find it so difficult to preach it. And why so many make various side steps here and there to either use it in a moralistic bludgeoning way, or use it as a way for you to get what you want out of God, or to just sort of mention it in passing and move on to more obviously moral life anecdotes.

Case in point, the Levite’s Concubine of Judges 19. Now, first of all, it must be said, that this is a terribly dark and difficult moment in the Bible, and in order to be able to face it, you Have to have some sense of who God is and who we are and what the Bible is for and about. If you’ve just randomly picked up a copy and started reading at Genesis 1:1, hoping for the best, by the time you get to Judges 19 I would expect that you’d be confused and disoriented. It’s no wonder that I’ve never heard one single solitary sermon on this text. It is brutal, devastating, apparently random, and, I would say, modern in its violence. If you feel like you can stomach it, you can go read the chapter and then come back.

Once having choked it down, you’re left wondering, as with the whole rest of Judges, who exactly the good guy is. We definitely have a victim, and we have foreshadowing, and we have mob violence, and we have the usual Adam problem of male passivity, and we have a brutalized and dead woman. And then civil war. We do have civil war. Which, frankly, I think is an appropriate response to such an occurrence. At least it was shocking enough that there was some kind of outrage. But the big hideous question is, where is God in all of this? Why didn’t he do something to stop it?

And that’s where you do have to have a continual robust preaching of the Bible, week by week, because the thing that happened to the Levite’s Concubine isn’t too far off from what happens all over the world every day. It’s a very ancient problem. Women are occasionally brutalized and destroyed–raped, beaten, left for dead. And the normal sane person asks, why do you let this happen, God?

Which question leads you to look at all the violence everywhere, and look at all the rest of the Bible and what God thinks about humanity, which is that it is continually wicked every day. All of us, every single one, wicked to the core. And in the face of so much wickedness and ugly brutality, where we would have come in (if we could have been good, which we really can’t) and just leveled the whole thing out in one single moment, God, being patient, lets us go on, all the time offering us the open door of repentance and salvation.

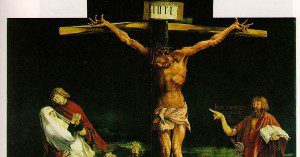

And really, look at the strange reversal. The Levite’s Concubine is the world’s Usual Sacrifice. The woman, the unborn babe–these can be taken and destroyed, cut up into bits and sent off in the mail. These are offered up as the appeasement necessary for happiness and freedom. But no where does God accept such a sacrifice. No, it is always a pure spotless male animal–all of which point to him, to Jesus, to the man taking up his life and laying it down in death for the salvation, the rescuing of the beloved. The death of the Levite’s Concubine is the world’s Anti Gospel. God’s response to it is the death of Son, the Second Adam, the true Gospel.

Which is quite an interesting moral, quite an extraordinary hero. The narrative is rich, complex, devastatingly packed with meaning. It’s an epic, really, that can’t be made more endurable with a song and some animation. It is the whole terrible wrestling of humanity with God and coming out on the limping side. It’s too big and too grand for three puppies and a poem. And ultimately, it is the undoing of each, the sword of the word of God deftly dividing joint from marrow, distinguished the thoughts and inclinations of every single human heart. But not for death at the final moment. No, rather for life, for restoration, for glory.