Part I: “It’s Jesus, Christian!” – The Conservative Struggle

Hebrews 1:1-4

pexels-photo-7219506

pexels-photo-7219506

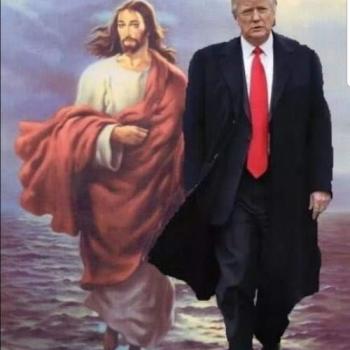

Introduction: Borrowing a metaphor from technology, the church needs to hit the reset button. When it comes to Jesus, there are viruses in our system. Jesus, the name of Jesus, drives some Christians crazy. While everyone in America wants Jesus on their side, there are more versions of Jesus than the kinds of bread in the supermarket.

Literalism Not a Way Forward

In fact, our presumption that we know what we are saying when we say “Jesus” indicates a deeper malady. For it turns out that we are most likely to not be speaking in the spirit of Jesus when we assume we can know what we say when we say “Jesus.” Preachers end up saying things like, “a desertion of historical Christianity.” For instance, Al Mohler looks like he just ate the bitter part of a pecan, when he claims that Andy Stanley has departed from biblical Christianity. Or Denny Burk, president of the Council of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, saying that Stanley’s sermon on LGBTQ persons was “subversively anti-Christian.”

When preachers refuse to swim in the deep waters of ambiguity, contingency, and probability, they spend their lives paddling around in the shallow waters of certainty, dogmatism, and the back of their necks turn a dark red. David S. Cunningham, in Faithful Persuasion, aptly says, “Persuasion cannot guarantee truth – and appropriately so for the work of Christian theology, which should always acknowledge that God alone embodies the fullness of truth.” Theological authorities of all sorts have claimed to speak the “truth” about Jesus, but their pronouncements at last crash against the rocks of wild, wild sea of the authority and the mystery of the triune God.

Literalists always feel like they are teaching the Bible in the same manner as my first-grade teacher taught me to read sound-by-sound, word-by-word, line-by-line in the Dick and Jane reading books. “See Dick run. See Jane skip.”

If you are ever tempted to think the first disciples or the early church got “Jesus” and it has been downhill ever since, I urge you to read Paul’s letters to the church in Corinth. We have never gotten it right. When Mohler and Burk put on their “inner” Apostle Paul and pontificate with declarations that make them sound as if they are the leaders of global Christianity, I have Kenneth Burke’s reaction to such absurdities: the “gaspo, gulpo, gaggo,” as he calls them.

Somewhere in this darkness I hear echoes of a greater knowledge: “For now we see only a reflection, as in a mirror, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known.” “I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings by becoming like him in his death, if somehow I may attain the resurrection from the dead.”

The Bodily/Fleshly/Material

Kenneth Burke argues that meaning never lies merely in words, but in the body and particularly in the sounds the body makes. His Piaget-inspired study does a number on literalism. Of particular interest here are words from Virginia Woolf, On Being III:

But of all this daily drama of the body there is no record. People write always of the

doings of the mind; the thoughts that come from it …. They show it ignoring the body

in the philosopher’s turret; or kicking the body, like an old leather football, across

leagues of snow and desert in the pursuit of conquest or discovery. Those great wars

which the body wages with the mind a slave to it, in the solitude of the bedroom against

the assault of fever or the oncome of melancholia, are neglected. Nor is the reason far to

seek. To look these things squarely in the face would need the courage of a lion tamer; a

robust philosophy; a reason rooted in the bowels of the earth.

The meanings, rooted in bodies, give the lie to the gnostic-inspired literalism of creationists, rapturists, and atonement theorists. As Wittgenstein reminds us, the real difficulty is one of the will, more even than of the intellect, or the words. What is hard is to will oneself to accept things that are true that one doesn’t want to believe, and moreover that perhaps one’s salary or one’s tenured professorship or one’s ability to stay in the good graces of the denomination depend on one not believing.

There’s Always More with Jesus

Philosopher Rupert Read says, “It takes strength, fiber, a true philosophical sensibility, to be able to acknowledge the truth; rather than to deny it.” Why literalists insist on seeing the “truths” produced by biblical criticism as a constraint on their thinking seems absurd. As Wittgenstein taught us, it takes effort and courage, and not mere intellectual acuity or assent, to demonstrate this in our approach to Jesus, i.e., to will to want to see reality, and to think and live accordingly.

No matter how much we experience Jesus, there is still more to experience. No matter how much we know about Jesus, there is more to know. In the Eucharist we discover that we cannot use Christ up. In the Eucharist we discover that the more the body and blood of Christ are shared, the more there is to be shared. The “body and the blood” take us where words cannot go. The Eucharist takes aim at an annoying, evangelical habit: the absenting of the body in Christian thinking and the fetishization of the disembodied idea. It makes sense to me that to take up the body, one has to take-up all of the body.

Jesus is so fleshly, so bodily, so human that knowing him means at least knowing more of all of humanity, including our own.