The Danger of a Politician Preaching a Sermon

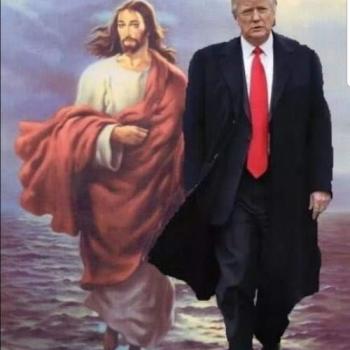

Photo by David Henry

There’s an embedded illusion among people about preaching: “Any old stick can preach a sermon.” An Episcopal Canon to the Ordinary once told me, “Having a preaching workshop for my preachers would be a waste of time. They all think they should be preaching at the National Cathedral.” Some of my preaching students felt a built-in disdain for the work required in a preaching class. Somewhere they had gotten the idea that taking a preaching class would be a welcome respite from the more difficult courses in biblical exegesis, systematic theology, and Christian history.

While we can easily excuse those who know little to nothing about preaching from entertaining such ideas, our elected politicians serving in the office of president, or the Senate/House should know better. Yet more and more politicians “fancy” themselves as preachers. Stanley Hauerwas famously said, “I often observe that it is unclear whether Texas politicians first started looking like Southern Baptist pastors or Southern Baptist pastors started looking like Texas politicians. Whatever the order, what is clear is that the church is always tempted to imitate the habits of those in power.”

Sometimes the results are hilarious. Donald Trump, speaking at Liberty University gave as his text a reading from “Two Corinthians.” He then preached a sermon encouraging the Liberty students to get even with their enemies. Most politicians should refrain from preaching sermons.

There have been exceptions to the warning. Abraham Lincoln’s agonizing sermons were works of theological brilliance rarely heard from any of our presidents. No president made more use of Scripture or preached more sermons to the American people than Frankline D. Roosevelt. His policies forged the Social Gospel of Walter Rauschenbusch and Washington Gladden into national policies and law.

Preaching requires a skillset not easily obtained. Caryle Marney confessed he spent forty years, hat in hand, before all the disciplines, seeking the power of the sermon.

Alan Gurganus eloquently testifies: “There are those who believe that the sermon is the primary literary form of American life. From Cotton Mather’s allegories of American guilt, to Whitman’s promissory hymns, to Twain’s biting moralizing satires, to Dreiser’s Ashcan School of Social Darwinism, to Faulkner’s postlapsarian South, to Flannery O’Connor’s godless modernity vs. ancient mysteries, to Marilynne Robinson’s watery, postmodern version of heaven and of hell in Housekeeping, we feel the sermon’s lash and balm in every great American book.”

Living up to the reputation of the sermon presents challenges to politicians inclined to preach. The lure of having one’s own tent and pulpit can be too much to resist.

There are two examples of a politician preaching that clearly demonstrate the dangers of such rhetorical efforts: President Jimmy Carter and Speaker of the House Mike Johnson. In each case, nothing negative is being said about the sincerity, commitment, and Christian faith of these politicians. Both Southerners, one from the more liberal camp, and one from the David Barton school of fake American history and a Christian nationalist, Carter and Johnson had similar failures with their sermons.

Jimmy Carter

On July 15, 1979, President Jimmy Carter addressed the nation. His subject: the energy problem. The speech was a sermon. Sounding like a Southern Baptist preacher, Carter’s sermon had three points: (1) A confession of sins; (2) A reaffirmation of his faith; (3) The determination to prove his faith by doing good works. Carter’s “sermon” was not a failure of content, but a failure to convince his audience. In no mood for national repentance, the people felt unfairly condemned by Carter’s sermon.

Perhaps no president has felt more the sense of failure that a sermon can produce like President Jimmy Carter. His so-called “Energy Sermon” fell flat on voters. The sermon was a Broadway play opening and closing on opening night.

Mike Johnson

Speaking at a weekend retreat for Republican members of the House of Representatives, Johnson’s long speech didn’t receive a favorable review. News reports posted “Republicans Didn’t Appreciate Mike Johnson’s ‘Horrible’ Religious Presentation at a GOP Event.”

Republicans were left scratching their heads after House Speaker Mike Johnson invoked God.

Johnson was speaking at a Republican retreat at a hotel in Miami when instead of dealing with the political issue at hand gave what amounted to a “horrible sermon,” the Politico website reported.

In his speech, the speaker focused on falling church membership and moral decline across the United States, two people who were at the event told Politico, speaking on condition of anonymity.

One representative said: “I’m not at church,” and said the speech was “horrible.”

The attendee continued: “I think what he was trying to do, but failed on the execution of it, was try to bring us together. The sermon was so long he couldn’t bring it back to make the point.”

Those who preach know the danger of the sermon being too long. The daughter of a preacher, coming home to her childhood church for the annual homecoming, said, “She’d made up her mind never to suffer through another of his meaningless, meandering sermons.”

Another congregant at a church in Georgia moaned, “Sunday after Sunday, mother and I sat through the droning of the preacher.”

Even for an evangelical-infused movement, Republican members of the House were turned off by Johnson’s sermon.

Politicians should beware selecting the sermon genre for rhetorical purposes. It is not true that “any old stick can preach.”