I began a new youth ministry job in the summer of 2006. Facebook was only two years old and was restricted to college students and a few tech companies. That fall it was finally opened to anyone over the age of 13. Not long after, one of the high school seniors at church suggested I should join. I was hesitant at first, surprised that students would want to interact with their 29-year-old youth pastor in this way. But I dove in and quickly realized what a powerful tool Facebook is for youth ministry. It would not be a hyperbole to say that Facebook revolutionized youth ministry for me. In fact, I’m not sure that I would have been as successful as I was in the context of that urban cathedral had it not been for social media.

For the next several years of ministry I continued to explore the possibilities of social media. My Facebook notes eventually turned into a blog. Then came Twitter and a variety of other platforms. I gave presentations at conferences and continuing education events about how to use social media in ministry. I started experimenting with “social media catechesis” as an element of my confirmation curriculum.

A decade later I still rely heavily on social media in my work and have been arguing for years that the mental model of social networks needs to replace the increasingly anachronistic understanding of church as a membership-based organization. In the debate between the dangers and benefits of social media, I tend to side with the perspective that social media mostly mirror the ways we would connect with others without these technologies—acknowledging, of course, that social media allow us to maintain many more peripheral and shallow relationships than we otherwise could.

But the recent presidential election is causing me to seriously reconsider my perspective on social media. Phrases like “echo chamber” and “balkanization” have been commonplace in our post-election processing. Throughout the campaign and in our various reactions to the election results, it’s obvious that we are a deeply divided nation—but it has also become painfully clear that we simply do not understand people who see the world differently than we do. Progressives have been especially surprised that so many people voted for Donald Trump because we live in bubbles of like-mindedness and never imagined that Trump’s support was as widespread as he claimed it was.

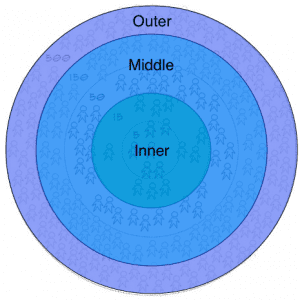

Is social media responsible for this? Not entirely, but they have exacerbated and accelerated trends that have been developing for decades. In The Vanishing Neighbor, a book I have found immensely helpful, Mark Dunkelman argues that Americans have deprioritized middle-ring relationships in favor of inner- and outer-ring relationships. These familiar but not intimate relationships with people from a variety of different backgrounds were the social building blocks that made the American experiment take off and succeed because they forced us to work with others—event those we disagree with—for the common good. Since so many of the cornerstone institutions of our society—churches included—were based on middle-ring relationships, the deprioritization of these relationships created the sense of social instability and partisan gridlock we have experienced in recent decades.

Faced with the adaptive challenges of this new reality, churches have two basic (though not mutually exclusive) choices: 1) find ways to reprioritize middle-ring relationships; or 2) find ways to be church in inner- and outer-ring cultural spaces (both in-person and online). While there are many good examples of the first option out there, my inclination toward (reasonable) cultural accommodation has caused me to focus more on the second option, reasoning that it is more productive for the church to adapt to cultural shifts than fight against trends well beyond our control.

However, it may be the case that these cultural shifts are simply too incompatible with the way of Jesus to allow a successful adaptation. Like-minded bubbles, echo chambers, and balkanization all thrive when we prioritize inner- and outer-ring relationships and invest little to nothing in middle-ring relationships. Despite the odds against redirecting the raging river of social media and digital communication, perhaps the church’s calling at this moment is to resist a complete adaptation and double down on the countercultural approach of middle-ring community building. This will require a different perspective on social media and how we use them.

While I can think of a lot of good resources out there to help us think about this—feel free to share your own suggestions in the comment section—for now, let me highlight two.

First, if you haven’t read Andrew Sullivan’s powerful essay on walking away from “living-in-the-web”, please do. Though Sullivan was certainly an extreme case of digital media addiction, his journey of self-awareness and change is a clarion call for Christians (and others) to retrieve long-forgotten spiritual practices. (Spirituality and metanoia—“changing hearts and lives”—happen to be the themes of the upcoming PYM conference.)

Second, I offer an overdue review and endorsement of Andrew Zirschky’s excellent book Beyond the Screen: Youth Ministry for the Connected But Alone Generation. Honestly, if I had reviewed this when I intended to several months ago I would have had a slightly different take on it. Andrew is much more persuaded than I am—was?—that digital communication is having a negative impact on our lives and our ability to live in meaningful community with others. On the other side of the presidential campaign and election, I’m much more sympathetic to his critique of networked individualism than I was several months ago. The core insight of this book is that teens’ use of social media reveals a deep desire for meaningful relationships. Andrew’s response is the Christian theology and practice of koinonia (communion). Right now, I can’t think of many things we need more than authentic koinonia. I highly recommend this book for youth workers (and others) navigating the changing nature of community in our digital age.

Second, I offer an overdue review and endorsement of Andrew Zirschky’s excellent book Beyond the Screen: Youth Ministry for the Connected But Alone Generation. Honestly, if I had reviewed this when I intended to several months ago I would have had a slightly different take on it. Andrew is much more persuaded than I am—was?—that digital communication is having a negative impact on our lives and our ability to live in meaningful community with others. On the other side of the presidential campaign and election, I’m much more sympathetic to his critique of networked individualism than I was several months ago. The core insight of this book is that teens’ use of social media reveals a deep desire for meaningful relationships. Andrew’s response is the Christian theology and practice of koinonia (communion). Right now, I can’t think of many things we need more than authentic koinonia. I highly recommend this book for youth workers (and others) navigating the changing nature of community in our digital age.

Ultimately, I don’t envision abandoning social media and digital communication technology altogether. That seems far too extreme. But I am definitely feeling challenged to figure out how to leverage these tools in ways that don’t become consuming or counterproductive.

Once again, there is far too much at stake to let matters like this slide.