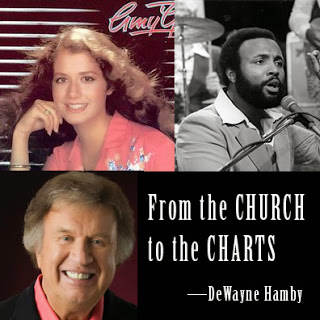

Back in 2005, Christian Retailing was celebrating 50 years of publication with longer articles about different aspects of the Christian retail business. As the music editor, I was asked to put together this retrospective of what happened in those fifty years. It is by no means authoritative, but I had fun speaking with some of the people who I felt shaped the musical landscape, including Andrae Crouch, Bill Gaither, Amy Grant and Billy Ray Hearn.

From humble beginnings centered around hymns and southern and black gospel styles, the gospel music industry has matured into an almost $1 billion-a-year business, featuring a message of hope with a variety of sounds from rap and hip-hop to bluegrass and country, with adult contemporary, inspirational and traditional in between.

Christian music in its many forms is heard on radio, bought and experienced in live and broadcast concerts by millions every year. Christian artists have made their mark on mainstream charts and airplay–but the widening audience for faith-centered music has not come without its tensions.

While 20 years ago, CBA-market sales accounted for 90% of all Christian music sales, that share has dropped to just 37% while 57% is accounted for by sales at general market stores like Wal-Mart and Target, according to the 2004 report by the Gospel Music Association (GMA). However, observers note that the sales currently tracked include recordings of inspirational albums by mainstream artists that CBA retailers may not stock.

Along the way musicians, producers and retailers have grappled with the challenges and opportunities of an art form that can powerfully touch lives.

While high-profile tours by Christian artists are commonplace these days, often filling mainstream venues beyond the traditional church circuit, 50 years ago only a few enjoyed the modest success and recognition to allow them to travel the country performing.

They were gospel performers like The Oak Ridge Quartet, The Blackwoods, The Speers, The Statesmen Quartet and the Five Blind Boys Of Alabama. When Bill Gaither, a key figure in the music industry, first started performing with his brother and sister in the early 1960s, he kept his focus on his job as an English teacher at Alexandria High School in Alexandria, Indiana.

“We started like a lot of groups started back in those days,” Gaither told Christian Retailing. “We were singing our way through college and preparing for doing something else for a living. The reality of doing gospel for a living was pretty slim.”

Gaither, who would later win the GMA’s Songwriter of the Year award eight times and be inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame in 1982, also recalled a stark contrast between today’s acceptance of gospel and the cultural mood of the early years.

“When we first started, it was a just a chosen few,” he said. “It was a subculture out on the edge of town. You didn’t go around bragging that you were a gospel singer, because most people didn’t know what that was.”

The possibilities of a wider retail market also came as a surprise for Gaither, who was normally accustomed to selling his products out of the trunk of his car. After one concert, a man asked him to leave him products to sell.

“(He said) ‘You’re going to leave town, then who’s going to sell your product?’” Gaither remembered. “That never dawned on me. I said, ‘sure’ and I left him some stuff. So to see that grow to where it is now where there are major distributors, it’s pretty amazing.”

Indeed, Gaither’s own contribution to the “amazing” growth includes the introduction of the phenomenally successful Homecoming series, with titles frequently landing at the top spot on Billboard Magazine’s Video sales chart and 29 of which enjoying multi-platinum certification by the Recording Industry Association Of America (RIAA).

While many southern and black gospel artists logged countless miles laying the musical foundation the industry built upon and still today enjoy wide exposure, it was the birth and subsequent success of contemporary Christian music that was the prime catalyst for the explosion of the gospel music scene.

The new sound was ushered in through the Jesus Movement, in response to the hippie movement’s impact on mainstream music in the 1960s.

“The Jesus Movement spawned a lot of artists that were just brand new baby Christians,” said John Styll, who founded Contemporary Christian Music magazine to celebrate the new genre, soon to become known by the initials to which the publication would later be abbreviated, CCM.

“They wanted to share their faith any way, any place they could,” said Styll, who went on to become President of GMA. “It wasn’t a vocational choice, it was a ministry calling. People weren’t really making money doing it.”

THE BIRTH OF A NEW SOUND

The movement included artists like LoveSong, Randy Stonehill and his “hippie” pal Larry Norman–whom many credit with releasing the first contemporary Christian album, Upon This Rock, in 1969. Much of the music came out of Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa, Calif., widely considered the epicenter of the emerging CCM scene.

An influential figure in many early CCM recording was Billy Ray Hearn, who had been recruited by Word Records in 1968 after gaining their attention for his collaboration with the Southern Baptist Association on the contemporary youth musical, “Good News.” He launched Myrrh Records as a home for the new CCM artists including 2nd Chapter Of Acts, Honeytree, Pat Terry Group and others.

On leaving Myrrh and forming Sparrow Records, Hearn signed Keith Green, who was regarded by some as a musical prophet for making music full of passion, conviction and rebuke. His musical messages were not always easy for listeners to take, yet songs like “So You Wanna Go Back To Egypt,” “Asleep In The Light” and “Oh Lord You’re Beautiful” still resonate with listeners decades after his untimely death in an airplane accident in 1982. Green was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame in 2002.

“He was sensational,” Hearn recalled. “We still sell his records.”

Other artists Hearn witnessed early were the members of Petra, who recorded their first two albums with Myrrh before moving to Star Song. The group would prove to be a major force in Christian rock– according to Mark Allan Powell’s The Encyclopedia of Contemporary Christian Music becoming “generally regarded as Christian music’s oldest and most successful rock band.”

While CCM continued to take form, black gospel groups and artists were to see their long-established genre exploring new territory. Although various black artists received significant notoriety as black gospel music gained in popularity, the music seemed to be segregated to black audiences in those early years.

As Jesus Music began to evolve into contemporary Christian music, an artist who would most successfully bridge the racial divide between it and black gospel was getting his start in a Los Angeles-based ministry.

“God put into my spirit as far as wanting more people to hear what I did, more people than I was around at the time as far as my local church was concerned,” Andrae Crouch remembered for Christian Retailing.

He formed The Disciples and become the face of a new contemporary form of gospel music. Songs like “Jesus Is The Answer” and “The Blood Will Never Lose Its Power” not only inspired churchgoing listeners but gained mainstream attention as the first contemporary group to achieve one million collective record sales, the first gospel group to play Carnegie Hall, and as one of the first breakthrough gospel performances on “The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson” and “Saturday Night Live.”

“It was a God thing,” Crouch said. “(The opportunities) had nothing to do with Andrae Crouch. I’m just glad that He used me.”

Crouch’s mainstream appearances would propel him to greater heights, but Christian music’s most visible media icon was herself on the verge of her biggest breakthrough in the early 80s. Signed by Chris Christian to Myrrh Records, Amy Grant was still a seventeen year-old student when her self-titled debut hit big.

Looking back, she recognized the importance of Christian bookstores in those early years. “Christian music started as such a grassroots industry,” Grant said. “There were some towns that had radio but a lot of them didn’t. It was these Christian Bookstores where you got information. People came there because they had a sense of community.”

With each subsequent release, Grant became more and more popular. In 1984, following Straight Ahead, she told Word she wanted to change her direction.

“I felt like any song with a spiritual message had a greater impact if it were heard around a lot of songs about regular life,” Grant explained. “I just feel like if every song talks about Jesus, I feel like I don’t have any credibility as a human being.”

Grant’s ideas were the creative catalyst for Unguarded, a project that would prove to be a turning point for the singer. The album also marked the beginning of a long-standing association with mainstream distributors A&M; Records. “Find A Way,” her first single from the record, achieved a status that many considered unthinkable–mainstream pop success.

Grant’s one-time backing band, DeGarmo & Key, had attempted to break through to the MTV audience with their video, “666,” but even after the video was edited to suit the network, becoming the first Christian title to air on the network, it didn’t continue to air in heavy rotation.

“It was always hoped that someone would have a song good enough to get played on top 40 radio,” said Styll. “Amy was really the first one to do that with any significance. When ‘Find A Way’ became a bona fide pop hit, that was a very exciting time in this industry.”

Once Grant opened the mainstream door of opportunity, there would be many others to follow—Michael W. Smith, Bob Carlisle, BeBe and CeCe Winans, Sixpence None The Richer and more recently, Switchfoot, Stacie Orrico, P.O.D. and MercyMe.

THE CHALLENGES OF ‘CROSSOVER’ SUCCESS

While mainstream acceptance has generated significant sales and helped legitimize their music, through the years Christian artists have frequently come under fire from some corners of the church for “crossover” songs that don’t specifically feature a gospel message.

The advent of Christian artists writing songs that spotlight human relationships and other various life issues forced the GMA to try to define, for purposes of its annual GMA Music (Dove) Awards, what actually constitutes a “Christian” song.

“You have to look at what the song says,” Styll said. “You can’t look at the lifestyle or beliefs of the artist or the record company or the market that it’s seen and heard in. It has to be strictly be based in what the product is.

“The problem we had is that as some of the artists tried to branch out lyrically, some of the music was not discernable gospel songs. For us to say the Song of the Year is [Amy Grant’s 1991 Hit] ‘Baby Baby’ would really stretch the limits of our credibility.”

A major contributing factor to crossover successes occurred in the mid-1990s when Billboard magazine, the Bible of the secular music industry, began to report Christian music sales drawn from the newly introduced SoundScan tracking of sales at CBA-channel stores.

In his book The Sound of Light, music business professor Don Cusic observed how the new technology meant that “the charts no longer had to depend upon phone calls to retailers who gave relative rankings. And the industry did not have to be victims of retailers prejudiced against gospel music.”

The charts have continued to document good news for the Christian music industry, with new projects from popular artists frequently appearing on Billboard charts. SoundScan’s 2004 report found the Christian/Gospel category of music sales to be the sixth most popular genre of all–Latin, soundtracks, jazz, classical and New Age genres.

But even with legitimate sales figures behind it, Christian music is still by and large not embraced in mainstream culture according to Styll, for whom that is a really good sign.

“It’s an economic force to be reckoned with and I think a lot of the world doesn’t want to reckon with,” he said. “But I think that’s a spiritual thing. To the extent that our music that our music is true to the Scriptures, then we’re always going to have that problem.”

The Christian music scene has at times followed mainstream trends, producing faith-based versionS of secular musical fashions, but the most significant trend of the past decade came from within the church.

Marantha! Music, spawned from the Jesus movement and Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa, California, first offered contemporary sounds for worshippers in the 1970s. In the 1980s, Hosanna! Integrity Music began as a mail-order business, ushered in a new wave of worship music that still dominates the sales charts still today. The Mobile, Alabama-based company has made a global impact through recordings like Ron Kenoly’s “Lift Him Up,” Don Moen’s “Give Thanks” and Hillsong Music’s “Shout To The Lord,” hand-in-hand with the rise of the charismatic movement and championed through publications like Charisma magazine.

As the charismatic worship of the church became more popular to those outside its wall and contemporary music began to find its way into church services, a modern worship emphasis began to occur through artists like Delirious, Matt Redman and Chris Tomlin. Soon, popular CCM artists were inspired to produce their own specifically worship-oriented.

Among them were artists like Michael W. Smith, Third Day and Newsboys, who found their worship records becoming among their fastest-selling releases ever.

While some have questioned whether or not the worship push is a truly trend or more of a marketing opportunity, others see it is as Christian music coming full circle.

“The Jesus people was a movement and the music came out of it,” Hearn said. “In the late 80s and 90s, there really was no ‘movement,’ the artists were their own ‘movement.’ They just kept producing music out of themselves, which wasn’t bad. But there was no movement until the worship movement came back around.”

No growth like that enjoyed by Christian music comes without growing pains. Although Larry Norman early on asked in his classic song “Why Should the Devil have all the good music?,” some conservative Christians continued to question whether sounds so often associated with worldly pleasures could be used for holy purposes.

“In the beginning, (CCM) had a huge struggle for legitimacy in the sense that there were a lot of religious leaders that were out there preaching about the evils of the beat or the drums,” Styll commented. “(They thought) the music was inherently evil in its style. ‘If it sounds like something that someone is using for evil purposes, then it must be evil’.”

THE ARTISTS COME UNDER SCRUTINY

Gaither also acknowledged the battles fought over contemporary music through the years: “It’s so different for people to separate their musical preferences from their theological absolutes. They get upset, they get angry. Keeping the saints happy but reaching out to a new generation that hears differently and sees differently has always been a fine line to walk.”

Hearn noted that in the early years of CCM, some retailers were so uncomfortable with it that they “didn’t want it in their stores” and would put the products in hard-to-see areas to keep customers from complaining.

The industry has also faced the suspicion of hypocrisy in performers. As mainstream doors were opened and some Christian artists began to experience previously unimagined heights of financial success, motivations came under question.

“In the 80s, it became a real industry where you had artists going, ‘You could have a career in this, you could do this to make money’,” Styll said. “That hadn’t happened in the beginning. That brought in some elements where maybe people weren’t really motivated by the right things.”

Artists found their lifestyles coming under close scrutiny. Through the years, artists like Sandi Patty, Andrae Crouch, Amy Grant and Michael English have faced retailer and customer backlash over confessions and/or allegations of moral failures, with their discs pulled from shelves and songs removed from Christian radio rotation.

Others artists left the field completely after their own personal struggles.

“We’ve had artists that have ‘fallen’ over the years,” Styll remarked. “People say that’s for various reasons. It puts a taint on this field. But great art is often very messy and sometimes lives are kind of messy.”

The mainstream acceptance of Christian music heralded another important change in the 1990s, as major Christian labels Word, Benson and Sparrow were taken over by mainstream companies.

Thomas Nelson first bought Word for $72 million, then sold Word Records to Gaylord Entertainment for $140 million, which in turn later sold the label to Time Warner for $87.1 million. The Music Entertainment Group purchased Benson Music and later sold it to the Zomba Music Group, which created Provident Music Group from Benson, Reunion, Essential and Brentwood labels.

The first of such recent transactions, EMI’s purchase of Hearn’s Sparrow Records, later followed by the purchases of Star Song and ForeFront, was a groundbreaking development that generated controversy that exists still today from those worrying about non-Christians owning Christian music.

“They all thought it was heresy, I’d gone to the devil,” said Hearn, now chairman of the EMI Christian Music Group. “But I did it to get the message out. It wasn’t to take the money and run. EMI did not change Sparrow one bit. It just gave it better distribution and more resources to reach more people and that’s what our purpose was.”

The risk now appears to have worked, as Christian music enjoys its widest distribution ever, combining both CBA and mainstream markets. As Cusic observed: “By having this dual distribution system, and paying careful attention to the core Christian audience in the Christian bookstores, these labels could reach a much larger audience.”

Although technology—in the form of Soundscan tracking–has brought Christian music some of its greatest blessings, it has also created one of its biggest challenges.

Since college student Shawn Fanning in 1999 created the highly controversial “Napster,” a system for illegally “sharing” digital music files via the Internet, music piracy has become a major concern for the entire music world—even impacting the Christian community.

“The survey we did earlier (in 2004) shows that only one in 10 born again Christian young people even see it as a moral issue,” said Styll, whose organization launched an awareness campaign warning Christians that such downloading was breaking the law.

The issue has brought to the fore again a debate that has existed in Christian music circles for years–should gospel music be free? At one time Keith Green demanded his music–like the gospel itself–be given away free, much to the dismay of industry gatekeepers.

Today, while some songwriters attribute credit to God for success, they grapple with the place of intellectual property. “The way I’ve resolved that in my mind is the creative process in the same way that somebody buys an album of whoever it is, regardless of the message, they buy it because they want to listen to the music,” commented multi-award-winning singer Steven Curtis Chapman.

Looking to the future, industry veteran Hearn sees a silver lining in the digital piracy challenge, as labels consider how to offer an attractive legal alternative.

“Once they work it out, I think that digital downloading will change things,” he said. “It’s only 5-10% of our sales now and it was 0% four years ago. It can’t help but grow. I think the internet gives young artists an outlet that they’ve never had before. They can make their own record and put it on the internet and have their own distribution. This makes entry into the market a lot easier and cheaper.”

Grant is pleased that some of the new artists coming onto the scene are not signing with the big companies whose interest in Christian music was sparked in part by her own success.

“They would rather do independent records and sell their music through the internet,” she observed. “The era of a few people getting a whole lot of promotion is now giving way to a lot more bands getting a chance. That might be a return to how it used to be–more about word of mouth, discovering artists on your own instead of being forced down your throat.”

For his part, Gaither sees no limits. “I think (the music industry) will go in any different direction depending on who is the new young charismatic person coming along that can attract audiences,” he said. “It’s hooked on a personality and if the personality’s strong enough, that could be Hungarian folk music for all I know.”