What is revelation? My definition broadens almost by the day. Sometimes I hear measures of a song so searingly truthful or beautiful they seem like prayer. Or I see a swallow swooping across a dawn-lit sky and the moment of perfection professes to me more than any sacred text. Other times, I read a passage in a book—maybe by George Eliot or Toni Morrison or Henry David Thoreau—that seems as laden with insight as any scripture, and I see the author must surely tune in to God as they write.

Though growing up in a conservative environment I heard the Bible was the sole vessel through which God revealed Godself, I now find revelation almost anywhere if I keep myself open.

So how do we receive revelation in a theological sense, with revelation meaning “divine disclosure”? We receive it through our senses (including “gut sense”) and experience. And we receive it subjectively, meaning it is subject to the lenses each of us brings to experience, lenses shaped by our culture and worldview and by other subjective lenses, like language. Which is to say, each of us receives revelation differently. And none of us receive revelation perfectly. The fact no human being can receive revelation perfectly does not mean we should discount the idea of revelation or be eternally skeptical. It does beg humility, though. Historically, religions have claimed perfection of their own divinely disclosed texts, while seeing manifest imperfection in the sacred texts of others. There is little room for this arrogance in understandings of revelation that integrate knowledge of how we know, of how the human brain is always making connections with what was experienced before—thereby building knowledge but also limiting our ability to integrate things entirely new.

Revelation, by Nature, is Individualized

Revelation must meet us where we are, to a certain degree, to allow our brains to make the neural connections by which we build understanding. This isn’t a handicap of revelation; it is part of its beauty. Divine disclosure meets us where we are—using the musical notes that evoke emotion specifically in us; or perhaps using metaphors in dreams that tell stories familiar to us, or leading us to stories or insights connecting with earlier revelation. When we take the revelation that meets the moment of our hearts and try to concretize or universalize it, calling it God’s truth for everyone, we fail to understand the graciousness and patience of revelation that makes itself a refraction of light meant just for our eyes.

When we broaden our understandings and openness to how revelation comes to us—through art, relationships, struggles, daydreams, literature, nature, smell, taste, feel—the world becomes enchanted and generous. God, the great regenerative force animating this universe—is available to us and offering Godself to us every day in myriad ways. Not merely when we crack open a certain text.

I deeply appreciate the purpose of a “canon,”[1] (literally meaning a “measuring stick”) and the need to have scriptures or collections of sacred texts that encapsulate a critical stage in the development of a tradition. We needn’t be changing or adding to our texts every decade willy-nilly as understandings change. But we should recognize that sacred texts encapsulate a time, and because understandings evolve, need augmenting. They are not enough. We need the writers of the Gospels and we need James Baldwin. We need the Psalms and we need Beethoven and Joni Mitchell. God not only speaks beyond the scriptures but feels and sings and chirps and breathes into every present moment.

Can we learn to stop second-guessing ourselves when this happens? Can we learn to trust the revelation happening all around us? Part of this practice surely involves redefining and relearning the meaning of revelation. Our Indigenous ancestors were much more skilled at hearing the revelatory cadence of the universe. Something about western culture post-Enlightenment made people in its thrall second guess anything sensory and non-cerebral, limiting revelation to what could be analyzed empirically or on a page, or discounting it entirely. Modern people need to re-learn revelation. Not only to nourish ourselves, but to nourish the natural world that increasingly speaks without being heard.

______

[1] “A biblical ‘canon’ is a set of texts (also called ‘books’) which a particular Jewish or Christian religious community regards as part of the Bible. The English word canon comes from the Greek κανών kanōn, meaning ‘rule’ or ‘measuring stick’…. Various biblical canons have developed through debate and agreement on the part of the religious authorities of their respective faiths and denominations. Some books, such as [certain] Jewish–Christian gospels, have been excluded from various canons altogether, but many disputed books are considered to be biblical apocrypha or deuterocanonical [meaning, ‘secondary canon’] by many, while some denominations may consider them fully canonical” (Wikipedia article on “Biblical Canon”).

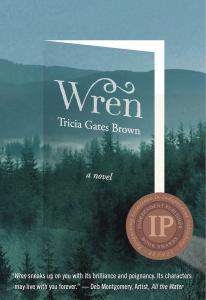

Wren, winner of a 2022 Independent Publishers Award Bronze Medal

Winner of the 2022 Independent Publisher Awards Bronze Medal for Regional Fiction; Finalist for the 2022 National Indie Excellence Awards. (2021) Paperback publication of Wren , a novel. “Insightful novel tackles questions of parenthood, marriage, and friendship with finesse and empathy … with striking descriptions of Oregon topography.” —Kirkus Reviews (2018) Audiobook publication of Wren.