By Brian Pennington.

I know he didn’t mean to, but last night, Morgan Freeman tripped over one of my major pet peeves. Not once, but a dozen times. All professors have them—pet peeves about things students routinely say or write that just set us off because they touch on some widespread misunderstanding of a concept or misuse of a phrase that drives us crazy. One of my grammatical pet peeves, for example, is “based off,” as in, “The movie was based off of the book.” A voice explodes in my head when I hear it: “It’s a structural metaphor! If there is a base, then a thing can only go ON it, not OFF it!” And don’t even get me started about “relatable.”

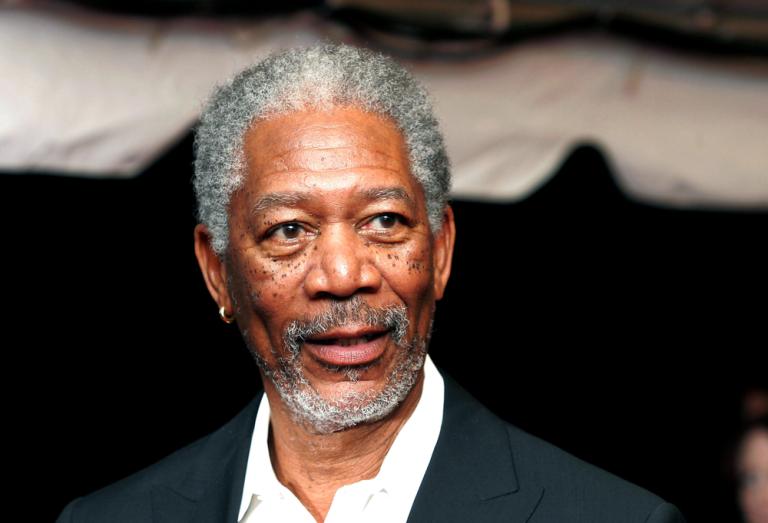

But I digress before I have even started. In last night’s third episode of the National Geographic Channel’s “The Story of God,” Morgan Freeman hit one of my major pet peeves: he described the objective of various religious behaviors as an attempt to “connect to God.” I hear this phrase a lot from students and others who are explaining what they think religion is about, and it always strikes me as empty, even lazy. Morgan used it repeatedly last night. Over and over. Each one felt like a personal betrayal: how could you, Morgan?

Last night’s episode, “Who is God?” was intended to address a couple of basic questions about the world’s religious traditions. Freeman put it this way: “Is there some universal concept of God [we] all share? Or is God fundamentally different to people of different faiths?” These are perfectly good questions, worthy of serious deliberation, and to the extent the episode pursued them, it did a passably good job: we were introduced to the Hindu conception of a divine force manifest in many deities of various forms and genders; we considered historical precursors to the Abrahamic monotheisms in Stonehenge and in Akhenaten’s Egypt, and we observed portions of a Navaho female puberty rite in which God enters the body of a human. Cool.

But in every single case, Morgan seemed preoccupied with a different question he hadn’t been completely upfront with us about: how does an individual in each of these traditions “connect” to God, and how relatively easy or hard is it to do so? When, as in Hinduism, God is an “idol,” he observes at one point, God is everywhere easily available and thus easy to connect to. When God is an invisible and distant entity, it’s harder to connect to him. (The fact that in such cases it’s always a him didn’t even seem to occur to Morgan.) If the goal is to understand how religion functions in the social order and how religions think and act differently from one another, this line of inquiry is misleading in a number of ways.

The first and most obvious one I won’t belabor: it presumes the presence or existence of some superhuman force and the need or desire of individuals to “connect” to it. It’s a theological question masquerading as an objective one. Second and more troublesome, however, is that it sets up a hierarchy of good and not-so-good religion. It forcefully implies that the purpose of religion is to allow the individual to develop a personal relationship with a divine entity who is, by that very model, also something of a person. If a religion does this well, by making God easily available, it succeeds in the presumed purpose of religion. If it keeps god distant and inaccessible to me and my needs, well, then it fails.

And here we begin to see a third and even more insidious deception this question of “connection” performs: the criterion for judging a religion’s worth is its serviceability to the autonomous, neo-liberal individual pursuing his or her own purpose and meaning in life, seeking satisfaction of his or her own individual desires in a capitalistic marketplace of religious options. It is a notion of religious life as consumerism, one that is profoundly individualistic and interior.

The question of how any religion enables a “connection” to the deity captures perfectly the concerns of the “spiritual-but-not-religious” set I discussed in my first blog post on “The Story of God.” As the episode’s closing monologue approaches and Freeman shifts from his Dogged Spiritual Explorer persona to the Voice of God persona, he concludes that Hinduism is profound and transformative because it allows me to coin my own personal version of God. But as it turns out, so is Joel Osteen’s prosperity gospel megachurch ministry because it gathers 10,000 people into a stadium rock every Sunday where they can “each of their own personal experience of God.”

If it’s about me, if it confirms my personal self-worth, if I can connect to some cosmic force that thereby ratifies my post-modern quest without challenging my choices or ideas too much—that’s good religion.

What gets lost when we think that religion is primarily about God and that all religion tries to “connect” with God (whatever that means)?

Take, for example, Morgan’s conversation with his archaeologist hosts at Stonehenge, who, told him about evidence they collected using ground-penetrating radar that revealed the presence of a prior shrine beneath Stonehenge. Presumably constructed by a different group of people, that shrine had faced away from, rather than toward the sun as Stonehenge did. The builders of Stonehenge crushed that previous monument and perhaps the society that built it to erect their own sun-worshipping shrine right on top of it and, one can only conclude, assert their own domination of the people they just suppressed.

But Morgan never saw it. Fixated on the question of God, he overlooked the fact that religion has social and political uses—that religion, perhaps, even distracts from noticing its social and political intention. Marveling at the builders’ profound monotheistic intuitions about the existence of a single divine being that they identified with the sun, he ignored the evidence right before him that screamed the violent suppression of a different group with a different God.

Gods are important to religion, but focusing on who God is can be a way of overlooking what we do with God. It’s about a lot more than just connection.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock