AP/Rogelio V. Solis

By Meri T. Long, University of Pittsburgh

It’s a common refrain of American voters: How can your party be so heartless?

Democrats want to know how Republicans can support President Trump’s policy of separating babies from refugee families. Republicans want to know how Democrats can sanction abortion. But does either party really care more about compassion?

In my research into the public’s support for a variety of government policies, I ask questions about how compassionate someone is, such as how concerned they are about others in need.

These questions are integral to understanding how people feel about who in America deserves government support.

Some people are more compassionate than others. But that doesn’t break simply along party lines.

I find that Democratic and Republican Party voters are similar, on average, busting up the cliché of bleeding heart liberals and uncaring conservatives.

And then there are Trump voters.

AP//Thomas Graning

Beyond partisan stereotypes

Compassion is defined by many psychology researchers as concern for others in need and a desire to see others’ welfare improved.

The similarity in compassion among voters of both parties contrasts with other measures of personality and worldview that increasingly divide Republicans and Democrats, such as values about race and morality.

Republicans are not less compassionate than Democrats, but my research also shows that there is a stark divide between parties in how relevant an individual’s compassion is to his or her politics.

Public opinion surveys show that you can predict what kind of policies a more compassionate person would like, such as more government assistance for the poor or opposition to the death penalty.

But for most political issues, the conclusion for Republicans is that their compassion does not predict what policies they favor. Support for more government assistance to the poor or sick, or opinions about the death penalty, for example, are unrelated to how compassionate a Republican voter is.

In my work, I find that the primary policy area where compassion is consistently correlated to specific policies for conservatives is abortion, where more compassionate conservatives are more likely to say they are pro-life.

Democrats predictable

When Democratic voters say they are compassionate, you can predict their views on policies.

They’re more supportive of immigration, in favor of social services to the poor and opposed to capital punishment.

Yet, while Democrats may be more likely to vote with their heart, there isn’t evidence that they’re more compassionate than Republicans in their daily life.

When it comes to volunteering or donating money, for example, compassion works the same way for Republicans and Democrats: More compassionate voters of either party donate and volunteer more.

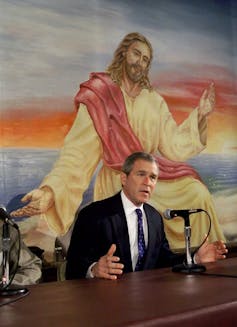

AP/Eric Draper

The real difference

My research suggests that voter attitudes about the role of compassion in politics are shaped not only by personal philosophy, but by party leaders.

Political speeches by Republican and Democratic leaders vary in the amount of compassionate language they use.

For instance, political leaders can draw attention to the needs of others in their campaign speeches and speeches on the House or Senate floor. They may talk about the need to care for certain people in need or implore people to “have a heart” for the plight of others. Often, leaders allude to the deserving nature of the recipients of government help, outlining how circumstances are beyond their control.

Democratic politicians use compassionate rhetoric much more often than their Republican counterparts and for many more groups in American society than Republican leaders do.

Do citizens respond to such rhetoric differently depending on what party they affiliate with?

When their leaders use compassionate political language, such as drawing attention to other people’s suffering and unmet needs as well as the worthiness of the groups in need, Republicans in experiments are actually moved to be more welcoming to immigrants and to support state help for the disabled.

This explains how Republican voters responded positively to Republican Sen. Robert Dole’s campaign for the rights of the disabled in 1989. It also explains the success of presidential candidate George W. Bush’s “compassionate conservatism” in 2000, which one Washington Post columnist wrote “won George W. Bush the White House in 2000.”

It also suggests that it’s not necessarily the public, but the party leaders, who differ so significantly in how relevant they believe compassion should be to politics.

AP/Jacquelyn Martin

Trump supporters the exception

Despite political rhetoric that places them at opposite ends of the spectrum, Republican and Democratic voters appear to be similarly compassionate.

Democrats view compassion as a political value while Republicans will integrate compassion into their politics when their leaders make it part of an explicit message.

There is a caveat to this: I asked these survey questions about personal feelings of compassion in a 2016 online survey that also asked about choice of president.

The survey was conducted a few days after Republican presidential primary candidates Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas and Gov. John Kasich of Ohio had dropped out of the race, making Donald Trump the only viable Republican candidate for the nomination.

In their responses to the survey, a large percentage of Republican voters said they would rather vote for someone other than Trump, even though he was the unofficial nominee at that point.

The Republican voters who didn’t support Trump were similar to Democrats on the survey with respect to their answers about compassion. Their average scores on the compassion items were the same. This is in line with the other survey data showing that liberals and conservatives, and Republicans and Democrats, are largely similar in these personality measures of compassion.

But Trump supporters’ answers were not in line with these findings.

Instead, their average responses to the broad compassion questions were significantly lower. These answers showed that Trump supporters were lower in personal compassion.

While a lot of the Republican voters in the sample may well have gone on to support Trump in the general election, the survey respondents who were early adopters of candidate Trump might continue to be his most steadfast supporters today.

We know that public officials’ rhetoric can influence public opinion on political issues. This leads to another important question: Can political messages influence how much people value compassion more generally? Or even how compassionate people consider themselves to be?

The research indicates that appeals to compassion – if made by trusted leaders – should work for voters of both parties.

But it also indicates that if such messages are absent, compassion is less likely to be seen as important in politics and the positions people and parties take.![]()

Meri T. Long, Lecturer, American Politics, University of Pittsburgh

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.