Brian LePort kindly posted a response from Craig Evans to my blog post about his recent article in The Bible and Interpretation (see also his paper on the subject on his web site). I will be the first to admit that, for Morton Smith to have been telling the truth about finding the text at Mar Saba, rather than having forged it himself, one has to accept some particularly striking coincidences, most notably the similarities with the novel The Mystery of Mar Saba.

I’m not sure whether everyone in their youth becomes fascinated with “mysteries of the unexplained” and spooky coincidences. I was. And one that comes to mind as I consider this is particularly relevant. In 1898, Morgan Robertson wrote a novel about a practically “unsinkable” ocean liner named the Titan, which strikes an ice shelf and sinks in the Atlantic Ocean in April, carrying less than half the necessary lifeboats for its passengers. The novel was called Futility or the Wreck of the Titan

.

Presumably there is little need to remind anyone that in April of 1912, an ocean liner named the Titanic met a similar fate in real life. Can the similarities between what actually happened and the earlier novel really just be a coincidence? I think that the answer must be yes, and if one acknowledges that such correspondences do occur from time to time by coincidence, then the appeal to Hunter’s novel to cast doubt on the authenticity of Smith’s find is at least somewhat undermined.

I will leave to one side the question of dependence on Papias, since my point was not that the Secret Gospel of Mark is not a forgery of any sort, but simply that we may have good reason to conclude that it is not a modern one perpetrated by Smith. That the letter of Clement in which the mentions of it are embedded could be an ancient forgery is a different matter.

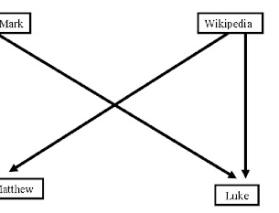

The suggestion that Smith had a well-developed view of Mark as depending on a source with Johannine characteristics prior to the discovery of the Secret Gospel, even if correct, would only explain why Smith made the case for Secret Mark being earlier than canonical Mark and thus pre-Johannine. But in fact, the source for this supposed view of Smith’s that I have found quoted most frequently is Smith’s review of Vincent Taylor’s book in HTR in 1955, an article which I am quite happy to say is accessible through JSTOR and EBSCO. In that review, Smith discusses Taylor’s suggestion that Mark 2:5ff combines two sources. That Smith would note the striking verbatim agreement with John in this story, particularly in an era that was witnessing an upsurge in the view that John did not depend on the Synoptics, is scarcely surprising, given the context. It is also scarcely a basis for concluding that he was thinking in terms of a general Johannine-type source for much of Mark. On the contrary, in the context of the review (p.26), Smith’s point is precisely that that story, which contains verbatim agreement with John, also features a public use of Son of Man which he considers typical of John rather than Mark, so that a source with Johannine traits is an explanation of elements of that one story, not the Gospel of Mark (whether canonical or in a different version) more generally.

Smith’s response to Taylor’s book also included a rejection on Smith’s part of Taylor’s rationalization of miracle stories as having derived from actual events that had more mundane, natural explanations. And that fact makes it striking that Secret Mark’s account of a resurrection akin to Lazarus’ has elements which would allow for the young man to have been alive and misdiagnosed as dead – precisely the sort of thing that Taylor proposed and which Smith objected to. And so here we would have Smith forging a document which would play right into the hands of his opponent. Why would he have done so? Why would he have pared from John those very details that could help Taylor or someone with a similar viewpoint counter Smith’s own argument?

I must confess that, having taken the time to think through a number of the points Evans made, the result is that I find myself less skeptical about the Secret Gospel of Mark than I was previously, rather than more. When I consider the above in tandem with recent handwriting analysis and the considerations I mentioned in my previous and other posts, my inclination is to view Morton Smith as having been essentially truthful about his find. But having said that, there are still many questions about Secret Mark and the letter of Clement that mentions it which remain to be answered, and among them is the possibility that, while the work may not be a forgery of Morton Smith’s, the Clementine letter and/or the Secret Gospel might be ancient forgeries. But that is a separate matter, best left for another time.