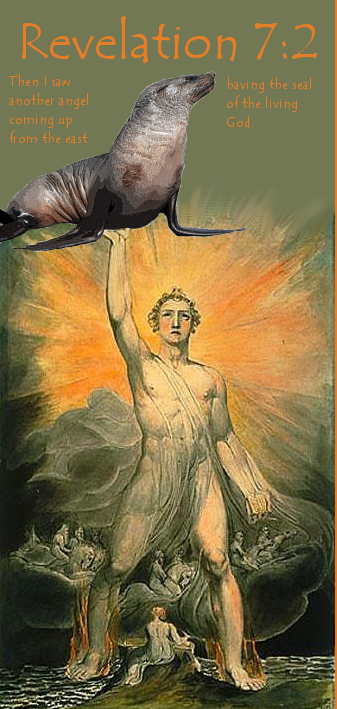

This past Sunday in my Sunday school class, we talked about Revelation chapter 7. Given my sense of humor, you won’t be surprised that I mentioned that Revelation 7:2 doesn’t mean this:

We also talked about how the chapter illustrates problems with both literalism and inerrancy. With literalism, not just because someone reading in English might think of the above when the read of an angel holding the seal of God, but also because the author makes reference to the “four corners of the Earth.” The author may well have meant that literally, but we cannot take it that way. And so it is up to the reader to determine whether the author held an ancient cosmology that we no longer do, or was speaking symbolically, but either way what the point of the language is and whether that is something that we can accept today. The idea that angels are involved in the harming of land, sea, and trees is no less problematic than the reference to the Earth having corners.

As for inerrancy, the list of twelve tribes is a problem, as anyone who actually knows the twelve tribes will spot, assuming they read carefully. The problem is not just the absence of Dan, for which which many have tried to come up with an explanation. The inclusion of Joseph as well Joseph’s son Manasseh simply doesn’t make sense. The author could have omitted Dan and included Levi, and the two Joseph tribes Ephraim and Manasseh, if the aim was to omit Dan. But as it is, the list is problematic.

It is ironic that groups which agree on the inerrancy of the Bible – from Jehovah’s Witnesses to fundamentalists within more mainstream forms of Christianity – have devoted a lot of attention to the identity of the 144,000, without spending as much time discussing why the list of tribes doesn’t make sense.

There is a simple and intuitive explanation for why the list is the way it is. Most people, if they try to rattle off a list of the twelve tribes, will not do nearly as well as the author of Revelation did. The author was a fallible human being, like us.

The point of the text is nevertheless clear – it reflects the idea that, even though there will be an enormous number of people from all over the world who come to faith, there will still be a subset of Israelites who do so as well. Early Christians had to wrestle with the fact that the majority of Jews did not accept their claim that Jesus was the Messiah. To cope with the cognitive dissonance, the author of Revelation, like Paul, seems to have embraced the view that there would be a significant number of people of Israelite descent who would believe – to be joined by an even larger number from the other peoples of the world. This was an expectation, not for some distant time in a future generation, which would by no means deal with what made this state of affairs so disconcerting, but for that generation, for the near future. And this did not happen, so here too we have something more troubling for the inerrantist than an erroneous list of tribes.

But when one reads the text not as fundamentalists do but with historical sensitivity, one can understand it, not as an offer of certainty about the future, but an expression of hope – hope that one’s own people would believe, hope that all people would worship the one true God, hope that persecution of the church would end and that those responsible for it would be held accountable.

For Christians today, thinking about God in the context of different historical circumstances and a different, science-enhanced understanding of the universe in which we find ourselves, we too must hope, but we cannot hope in exactly the same way that the author of Revelation did. Our hope for the future, in our time, cannot be his, but must be our own.

Our hope for the future may be less about “us vs. them” and more about justice not only for our own group but for all.

Our hope for the future may have every bit as much to do with envisaging a future in which people do not elevate human beings – or their own society or empire – to the status of deities.

And our hope for the future in a world that has seen the spread of democracy will involve less simply waiting for divine intervention, and more action on our part to bring about change in the world.

What do you hope for? What do you think that Christian hope in our time ought to look like? How might, and how should, it be different from that of the author of Revelation?