Here I am continuing some preliminary reflections related to my upcoming conference paper (which I began in an earlier post). My research interests which intersect with the methodological question I raised in my previous post, about the discerning of ancient traditions and of independent traditions in relatively late texts, seem to revolve around Johns and Thomases.

Here I am continuing some preliminary reflections related to my upcoming conference paper (which I began in an earlier post). My research interests which intersect with the methodological question I raised in my previous post, about the discerning of ancient traditions and of independent traditions in relatively late texts, seem to revolve around Johns and Thomases.

I’ve looked at the Gospel of John and the possibility that it could contain information which is not dependent on the other canonical Gospels, and I’m also interested in the same possibility for the much later Mandaean Book of John. And I’ve looked at the question of historical information in the Acts of Thomas (Johnson Thomaskutty also just posted about the traditions of the Mar Thoma Christians of South India related to Thomas’ visit), and remain interested in the question whether the Gospel of Thomas, even if it shows the impact of influence from the New Testament Gospels, could also incorporate independent tradition.

A crucial question is what kind of differences, if any, are indicative of there being independent information?

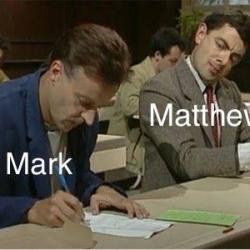

Mark Goodacre (in his book Thomas and the Gospels: The Case for Thomas’s Familiarity with the Synoptics, which I’ve recently begun reading) rightly emphasizes that differences can never, in and of themselves, provide evidence of absolute independence. He points out legal decisions involving cases of plagiarism, and the conclusion (in Sheldon vs. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures) that “No plagiarist can excuse the wrong by showing how much of his work he did not pirate” (quoted Goodacre p.55).

But in some instances, that a particular author “plagiarized” is not in doubt. The question is whether, if Matthew knew Mark, or John or Thomas knew the Synoptics, the later author could still have also known a saying or story independently of encountering it in the written source, and have either written the version they already knew, or incorporated other details that they already knew as part of the story into a version which also incorporates elements from the written source before them. That – and the related question of, if we accept that there may be such instances, how we recognize them – is/are the question(s) that I am interested in wrestling with.

In relation to that question, and the related one of later scribal changes influenced by particular texts, Goodacre sums the matter up particularly well in this marvelous statement (p.58):

The issue of the relationships among ancient texts is often complex, and our explanatory models all too often create the impression that complicated relationships, in which there were hundred of points of contact and divergence between texts and traditions, can be reduced to simple, unidirectional diagrams with only two or three dots and arrows.

So if you granted that Matthew knew Mark, Luke knew Mark, John knew Mark and perhaps others of the Synoptics, Thomas knew the Synoptics, and the Mandaean Book of John knew one or more of the New Testament Gospels, and wanted to investigate whether the later author also had access to other traditions, whether oral or written, then what would you look for in terms of evidence for such independent (or, if you prefer, semi-independent or prior) knowledge?