I just recently started meeting with some colleagues and a student in a Greek reading group. I suggested to a colleague in Classics that it might be interesting to read Philo of Alexandria together, and she got very excited about the idea, and some other colleagues in Religion also expressed an interest.

And so lately, I have felt disconcertingly like I am back in Greek class, wondering why the verses that I end up with when it is my turn to read and translate are so difficult, while those others end up with seem comparatively easy. Of course, if I had been preparing for “class” as I should have been, I probably would not have felt that way. 🙂

And so lately, I have felt disconcertingly like I am back in Greek class, wondering why the verses that I end up with when it is my turn to read and translate are so difficult, while those others end up with seem comparatively easy. Of course, if I had been preparing for “class” as I should have been, I probably would not have felt that way. 🙂

But kidding aside, it is intended to be a low-pressure, enjoyable experience in which we read and if necessary muddle through together. Although we’ve only met twice, I am already finding it a really rewarding experience. Doing this is relatively straightforward thanks to the availability online without cost of editions of the Greek text, as well as Yonge’s older English translation.

We are reading his “On the Creation” (known in Latin as De opificio mundi and in the original Greek as Περι της κατα Μωυσεα κοσμοποιιας). It is worth reading for many reasons, not least of which is the clear evidence it provides that the so-called literalism of some contemporary interpreters is not “the traditional approach” to the creation accounts in Genesis. III.13 is particularly illustrative:

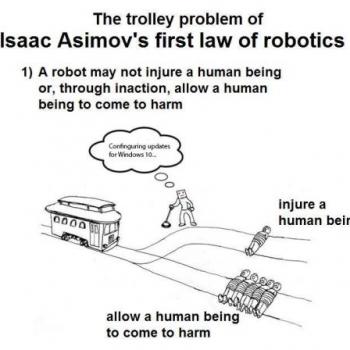

Ἓξ δὲ ἡμέραις δημιουργηθῆναί φησι τὸν κόσμον, οὐκ ἐπειδὴ προσεδεῖτο χρόνων μήκους ὁ ποιῶν – ἅμα γὰρ πάντα δρᾶν εἰκὸς θεόν, οὐ προστάττοντα μόνον ἀλλὰ καὶ διανοούμενον – , ἀλλ’ ἐπειδὴ τοῖς γινομένοις ἔδει τάξεως. τάξει δὲ ἀριθμὸς οἰκεῖον, ἀριθμῶν δὲ φύσεως νόμοις γεννητικώτατος ὁ ἕξ· τῶν τε γὰρ ἀπὸ μονάδος πρῶτος τέλειός ἐστιν ἰσούμενος τοῖς ἑαυτοῦ μέρεσι καὶ συμπληρούμενος ἐξ αὐτῶν, ἡμίσους μὲν τριάδος, τρίτου δὲ δυάδος, ἕκτου δὲ μονάδος, καὶ ὡς ἔπος εἰπεῖν ἄρρην τε καὶ θῆλυς εἶναι πέφυκε κἀκ τῆς ἑκατέρου δυνάμεως ἥρμοσται· ἄρρεν μὲν γὰρ ἐν τοῖς οὖσι τὸ περιττόν, τὸ δ’ ἄρτιον θῆλυ· περιττῶν μὲν οὖν ἀριθμῶν ἀρχὴ τριάς, δυὰς δ’ ἀρτίων, ἡ δ’ ἀμφοῖν δύναμις ἑξάς.

I’ll offer my own rough translation of the first sentence: “He says that in six days the world was fashioned – not because the Maker required a length of time (for it is natural for God to accomplish everything at once, not only in commanding but even in thinking), but because the things being brought into being required arrangement. And numbers administer arrangement…”

The rest finds mathematical significance in the number six. None of what Philo writes on this topic in the passage bears even the slightest resemblance to how modern-day fundamentalists approach the text.

I wonder how many people who read this blog have ever read Philo in Greek. This is my first time trying to read an entire work of his in the original language, and is an expression of my longstanding desire to read more in Greek beyond the New Testament. I am grateful to colleagues in Classics for joining me in doing so – and hope we can keep it up!