I am grateful to have been given the opportunity to participate in the blog tour focused on T. Michael Law’s book, When God Spoke Greek: The Septuagint and the Making of the Christian Bible

. It is a book about the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Jewish Scriptures, and why you should be more interested in it than you probably are.

In case you missed the blog tour thus far, Joel Watts started off the blog tour, followed by Andrew King, then Krista Dalton, then Abraham K-J (who has been responsible for leading a group spending a year reading through Greek Isaiah), then Jessica Parks, then Amanda McInnis. Brian LePort has also been asking discussion questions related to the book. And of course, Law’s own blog is also a place to go for interesting thoughts related to the book – as well as a funny parody of the Fox News interview with Reza Aslan! The conversation has spread elsewhere too – for instance, Nijay Gupta’s blog.

My role in the blog tour is to blog about the final chapters of the book. The penultimate chapter, chapter 13, is one of a number of colorfully-titled chapters in the book: “The Man with the Burning Hand versus the Man with the Honeyed Sword.” In case it wasn’t obvious, the two figures are Augustine and Jerome, and the focus of the chapter is the debate between the two over the status of the Septuagint, and Jerome’s work to create a new Latin Bible based on the Hebrew text.

The chapter returns to the Alexandrian allegorical approach and the contrasting Atiochene school, discussed in more detail in a previous chapter. Eusebius of Emesa is said to have been something of a bridge between the two, and having been fluent in both Greek and Syriac, he was aware in a way that few others had been of the status of the Septuagint as translation. This Eusebius was a major influence on another person of that name, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus, whom we know as “Jerome.”

Law helpfully highlights the strengths and weaknesses of the arguments used by Jerome and Augustine, as well as the different contexts within which they lived and worked. Jerome, living at various times in his life in places like Antioch and Bethlehem, was more directly aware of and involved in Jewish-Christian dialogue than was Augustine, and this surely shaped his views.

On the other hand, Law is very up front about the difference between Jerome’s own estimation of his ability in Hebrew, and the reality: Jerome “became like a first-year student with a semester of Hebrew under his belt. He knew just enough to be dangerous” (p.156). And some of the arguments Jerome used to argue his case – such as his claim that the New Testament authors never used the Septuagint – were spectacularly and demonstrably wrong (p.158).

I felt that the chapter wrapped up a little too abruptly. Early in the chapter, it had been mentioned that there was concern that a new Bible would undermine the church’s unity, but by the end, it is suggested that the Western church was gathering around Jerome’s Bible in an attempt to preserve unity. A bit more clarification on and detail about the dynamics of how events unfolded, and the political and church hierarchical support which affected this change, would have been useful. But on the whole, the chapter does what it aims to, namely indicating how the shift away from the dominance of the Septuagint began to come about, and how the “apocrypha” was created as a category in the process.

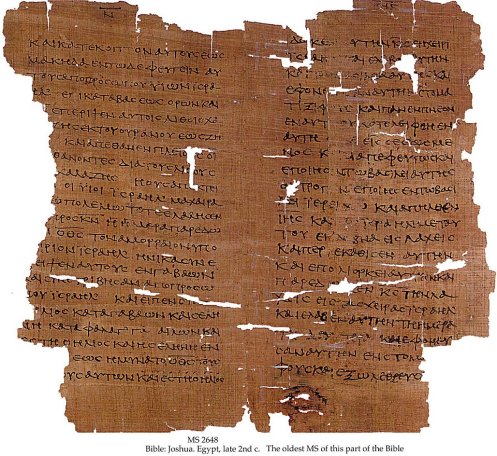

Chapter 14 is called “A Postscript” – but it is not to be neglected, as it really represents an attempt to bring together the threads of the book, and offer suggestions for where scholarship might go in response. Law emphasizes that the focus on getting back to an “original text” is a modern concern, even if it has some ancient roots. I might also add that the exclusive focus in some circles on the Hebrew Bible reflects a dubious theological presupposition: that the penning of those works in more or less their present form represents the singular moment of inspiration, when an allegedly inerrant text comes into existence. Yet all but a handful of extremists will accept that there were written sources which went into the creation of the Hebrew Bible as we now know it, and that in the process of copying errors and changes have crept in. That being the case, focusing exclusively on the Hebrew Bible, or more precisely on the the moment the works of the Hebrew Bible were penned, makes little sense for those interested in the history of the Jewish and Christian Bible(s). And just as one cannot make good sense of the history of Judaism and Christianity in the English-speaking world by ignoring English translations, one cannot fully understand or appreciate the history of Judaism and Christianity in the Greek-speaking world – including but not limited to the very beginnings of Christianity reflected in the New Testament – without studying the Septuagint.

Law expresses his hope that there will be increased scholarly attention paid to the LXX in its own right, and not merely as a means to some other end. He likewise hopes that the LXX will get greater attention from theologians. The LXX is a translation which in many places reflects a particular theological outlook (p.170). Just as those who read English translations are influenced by the theology of those who translated it, so too the church’s theology cannot and should not be explained without some indication of its debt to the theology of the LXX translators.

Law expresses his hope that there will be increased scholarly attention paid to the LXX in its own right, and not merely as a means to some other end. He likewise hopes that the LXX will get greater attention from theologians. The LXX is a translation which in many places reflects a particular theological outlook (p.170). Just as those who read English translations are influenced by the theology of those who translated it, so too the church’s theology cannot and should not be explained without some indication of its debt to the theology of the LXX translators.

Law also emphasizes more than once in these chapters that the obscurity of certain words and passages in the Septuagint was reflected and embraced in the theological viewpoint – articulated equally by Augustine in the West and by Ephrem in the East – that finding a single meaning of the text does not exhaust the riches of the text. I get the sense that Law sees in an appropriate appreciation of the role of the LXX in the church a resource that can help the church move away from the modernist-fundamentalist quest for the one true original text, and the one correct interpretation thereof, towards a stance that more closely resembles the early centuries of the church, when no such concern existed in anything like the form it sometimes takes in our day and age.

Since Law’s book ends not with his drawing things to a close, but with his expressing the hope that he has opened a door that others will walk through, I feel as though I should not try to wrap up this blog tour – other than to recommend When God Spoke Greek and encourage others to read it! But instead of a “conclusion,” let me offer an open-ended challenge to readers, whether they be scholars, Christians not involved in the academy, or other persons interested in ancient religion: What could you do, or start to do, to become more acquainted with the Septuagint? What impact do you think it might have on your scholarly work, your spiritual life, your understanding of the past, or all of the above?