I am grateful to Eerdmans for providing me with a free review copy of Tony Burke's recent book, Secret Scriptures Revealed: A New Introduction to the Christian Apocrypha

. As Burke says towards the end of the penultimate chapter, his book “is merely an appetizer; the main course awaits” (p.150). The volume manages to squeeze in an impressive amount of material into its 164 pages. But it is not intended to provide a comprehensive treatment of the material or to replace the reading of the texts themselves.

What the volume does, and does well, is to provide enough information to help a newcomer to these texts understand their significance, situate them historically, clarify which modern-day claims about them are mere sensationalism, and whet one's appetite so that one becomes eager to read them.

The book brings Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code into the picture right from the beginning, noting that the novel has proven useful in generating interest, but has also led to misperceptions. Interestingly, conservative reactions to the sensationalized claims closely mirror the reactions of ancient conservative Christians to the texts themselves. Burke aims to provide a balanced and sober discussion of the texts. And this he achieves. Towards the end of the book, Burke writes (p.151):

As it happens, the only 'truth' to be found in these texts is that Christian writers sure had vivid imaginations. They did their thinking through story, taking characters near and dear to their fellow Christians and casting them in tales in which their speech and actions offer guidance for readers living in the writers' own time. Little of the material from the stories is likely to have originated with Jesus and his contemporaries, though it is not impossible. In my thinking, it doesn't really matter. The value of the texts, as often stated in the preceding pages, is in what they tell us about Christianity, not Christ. Each story, each saying, discloses something about the writer and the community in which he or she belonged – their beliefs, their practices and their responses to the world around them. That is what these secret scriptures reveal.

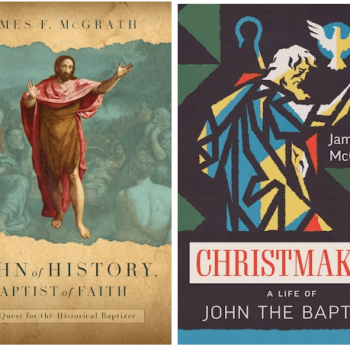

So many works are surveyed that there is likely to be one that even a scholar who reads the book is unfamiliar with (e.g. Serapion's Life of John the Baptist in Garshuni). Along with introductions to the authorship, date, and contents of individual works, many other subjects are treated, including the poor communication between liberals and conservatives, and the crises of faith that sometimes occur when those who have been exposed to the BIble but not BIblical scholarship encounter academic study of the Bible or of extracanonical texts for the first time. The volume also mentions the influence of the extracanonical texts on art, drama, and other literature – from ancient times down to Tori Amos' “Original Sinsuality” which draws on the Apocryphon of John.

The material about Jesus is grouped together by what it covers, so that lives of Jesus, and texts that focus on the passion and/or resurrection, are found in tandem in the same chapter, aiding comparison and contrasting of their details.

I also appreciated the discussion of aspects of the Secret Gospel of Mark that a general audience may not be aware of, such as the results of the handwriting analysis (p.62). Although it does not seem at all possible that Morton Smith could have produced the work himself, that does not mean that the work is not a forgery, perhaps even a relatively late one, but only that the forger had a native ability in Greek that surpassed Smith's.

The book has occasional weaknesses, of course, as all books inevitably do. For instance, I found the discussion of Walter Bauer's view that “heresy” preceded orthodoxy to be less than helpful (pp.145-6). If that topic was to be raised, then (in my opinion) at least a little more ought to have been said about the continued popularity of Bauer's thesis despite it having been shown to be wrong on many details, and how one can learn from those appropriate challenges to tradition, while also being open to revising or jettisoning the view argued for when further analysis requires it. But even on this point, my complaint is that more ought to have been said, and some key points clarified. Since Burke's aim is to introduce and to open discussion rather than resolve it, that may perhaps have been accomplished effectively even on this topic.

The book ends with an annotated list of useful places to turn next, including books but also blogs and websites. And in case anyone reading this is not aware of it, Tony Burke has a blog that is worth following, Apocryphicity.

I highly recommend this volume. It really should be read by, and available on the shelf as a reference volume for, anyone who works on or is interested in early Christianity and its literature.