In an interview that Richard Carrier gave on the show Inspiring Doubt, Carrier said that I am a great example of bias.

He is, of course, correct.

Let’s take Christianity, for instance. I grew up in a country where Christianity predominates. I grew up in a family in which I was raised in one of the many forms of Christianity. I had a life-changing experience in the context of another form of Christianity. I am currently a member involved in the life of a local church.

If that doesn’t make me biased, I don’t know what would.

I could of course point out that, as a liberal Christian, I am committed to embracing the results of mainstream science, history, and other branches of scholarship. I am agnostic about a great many things, and treat claims to the supernatural with skepticism. I could point out how often I have learned from non-Christians, and how frequently I agree with atheists even against other Christians in discussions.

But none of that would change the fact that I am biased.

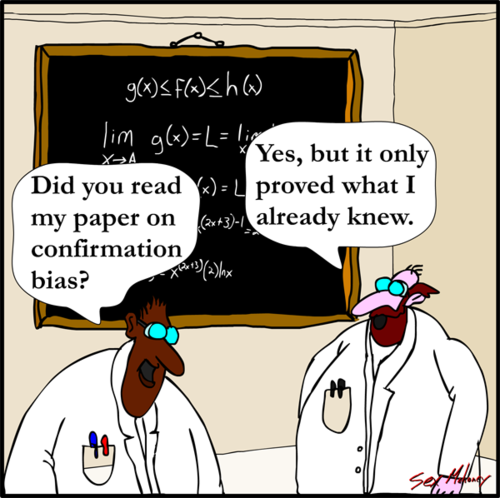

What worries me is that Carrier’s accusation suggested that he thinks he isn’t biased, and that only those who disagree with him are.

If I say something favorable about Christianity, then that may well be my biases. Of course, the fact that the view of the historical Jesus I end up with as a result of historical investigation creates more problems for Christianity than a mythical Jesus would ought to be considered as well. How can conclusions that run counter to what most Christians would like to be true be the result of my alleged “Christian agenda”?

But be that as it may, the answer to this problem of bias is not for me to show how I manage to make arguments and draw conclusions that run counter to my biases. The solution is rather precisely what Carrier is trying to lure people away from in the historical investigation of Jesus: looking for a consensus, expecting the community of experts with its diversity of biases, its critical methods, and its rigorous standards of argumentation to provide the best counterbalance to the biases that we all have.

If I make a case for something as a scholar, the onus is on me to persuade my peers in the field. If I am unable to persuade them, then the odds are that I am wrong, although only time will tell.

Committing oneself to that scholarly enterprise, with its humbling implications, is really hard. It is not surprising that some prefer to try to bypass the rigors of peer review and to deny the painful implications when our ideas do not meet with acceptance in the academy.

I choose to pursue the path of scholarship, with its acknowledgment that we are all biased, and its provision of the best scholarly methods we’ve come up with to minimize the distorting impact of our biases. Because the alternative may appeal to my ego, but it seems dubious to my reasoning.

And the consensus of scholars is, I believe, with me in that judgment.