You probably know Eric Reitan for his excellent and insightful nonfiction books. In addition to a number of theological and philosophical interests that he and I share in common, we also both enjoy reading and writing science fiction. Eric has a new novel out, So Eden Sank to Grief, and I’m delighted that he’s agreed to do an interview for my blog. My questions are in italics and Eric’s answers follow indented below.

What is your novel, So Eden Sank to Grief, about?

So Eden Sank to Grief centers on Caleb and Sally, two high school seniors with histories of trauma, who find themselves alone together in a strange kind of paradise: a vast greenhouse floating in a star-rich corner of the galaxy. They have no memory of how they got there, but they start having visions of Earth’s destruction. They eventually get the sense that these visions are the efforts of the ship’s creators to communicate with them.

Unfortunately, they don’t have a lot of time to try to puzzle out what’s going on and what the aliens are trying to say, not only because they’re caught up in new love but because other refugees from Earth start waking up in far-flung corners of this habitat…and not all of them are exactly benign. Soon they’re running for their lives—and headlong towards a face-to-face confrontation with their own histories of trauma. If they’re going to wrestle with the mysteries about this celestial greenhouse and its alien creators, they’ll have to do it on the run.

You’re a philosopher of religion and ethicist. How does that impact the novel? Any philosophical themes you explore? More broadly, how does your work as a philosopher inform your fiction?

So just yesterday I was reading one of the first Amazon reviews of the book to appear—written by a philosophy instructor—and was stunned by the number and variety of philosophical themes that he identified.

If I’d been answering this questions a couple of days ago, I’d have said that the book explores themes of belief-formation amidst uncertainty, patriarchy and its relationship to rape culture, and the promise and perils of nonviolent responses to violence. I probably would not have thought to mention all the things the reviewer does, even though all those things are definitely there.

But none of them are the meat of the story. If you’ll pardon the bad simile, they’re more like what the meat has been marinating in: the spicy, sherry-spiked broth that’s seeped in to give the meat a distinctive flavor.

And that relates to the other part of the question: How does my work as a philosopher inform my fiction? Here, I think it may be best to say how it doesn’t. Philosophy is all about developing and refining arguments in the light of objections so as to decide which answers to abstract questions have the best arguments in their favor. If that kind of thing starts creeping too much into your fiction, the best you can hope for is that it will be boring. Worse, it’ll be preachy.

Fiction, like philosophy, often deals with big questions about the human condition. But it does so in a different way than philosophy. What fiction does really well is invite us to wrestle with big questions by confronting us with story situations that give rise to those questions. It can also dramatize dimensions of the human experience that shed light on those questions. It can move us to care about the questions because of how they impact the characters’ lives.

But in good stories, what needs to take center stage is this: believable characters with problems who try to solve their problems. Along the way, they might confront philosophical questions and talk about them with others (hopefully not in the way most philosophers do). But as soon as answering big questions becomes the point, the story is dead. (I’m looking at you, Ayn Rand.)

So, how does philosophy shape my fiction? First, I probably think more explicitly than others do about the philosophical outlook my characters have. And I put characters—sometimes consciously, often not—into situations that raise philosophical questions or shed light on them.

But I have only once had a character in a story who was an academic philosopher: one of my first short story publications, “A Socratic Pacifist in King Arthur’s Court.” And that was satire.

It has become so common for authors to offer sci-fi retellings and explorations of biblical stories that they came up with a genre label for it: “shaggy god stories.” Perhaps none is more popular than Adam, Eve, and the Garden of Eden. Knowing this, what led you to decide to lean into that trope and embrace it, and yet at the same time to think you could offer (as you do) something genuinely new within that genre?

I didn’t start out intending to write a Garden of Eden story. So Eden Sank to Grief actually started out as a parable on my philosophy of religion blog about a group of people who wake up on a spaceship with no memory of how they got there. Some have visions of the Earth destroyed. Others don’t. Those with visions disagree about their meaning. My aim was to raise questions about what’s reasonable to believe in the face of uncertainty and ambiguity—with a special focus on whether it can be reasonable for someone confronted with mystical experiences to treat them as an encounter with something real as opposed to just neural misfirings.

But when I revisited that parable later, I thought, “This has Lost vibes. There’s a novel in here.” My first pass at the opening had the main character, Caleb, wake up in a Star-Trekky spaceship.

I hated it. I tried again. He woke up with his face in the dirt. Dirt? On a spaceship? It became a greenhouse. A vast, lush landscape-under-glass for him to explore.

Being a “pantser” rather than a “plotter” (that is, I write my first drafts by the seat of my pants), I watched my main character as he took in this environment. I wondered where this was going.

Then he met Sally. Even then, I didn’t know I had a Garden of Eden story. As I wrote, Caleb and Sally took me on a journey that was about their trauma and grief—things you don’t typically find in the Garden of Eden. And when they encountered other people, it became about the steadily building conflict and the horrible possibility that a handful of humans could be rescued from the destruction of Earth only to destroy one other.

It wasn’t until I’d finished a first pass that I realized I had a Garden of Eden story. But by then I’d crashed unexpectedly into the Garden of Eden from the back, with a story-load of things I’d never have thought to put in a Garden of Eden retelling if that’s what I’d set out to do. Now that I was here, smack in the middle of such a story, I had to figure out how to make the pieces fit.

So, if there’s something fresh or new, I think I have that to thank.

What are some of your influences and favorite authors?

As a kid, the first books I ever fell in love with—I mean head-over-heels in love—were Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings books. After that I gobbled up LeGuin’s Earthsea trilogy, McKillip’s Riddle-Master trilogy, Burroughs’ Martian Chronicles, Azimov’s Foundation books, Frank Herbert’s Dune books. As long as it was set on an imaginary world, I was game.

In high school I read Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun and LeGuin’s Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness—and for the first time I found myself wishing I had written that.

In recent years, I’ve loved literary science fiction novels, such as those of Justin Cronin and Emily St. John Mandel. I’ve also found myself increasingly drawn to horror novels like Tremblay’s A Head Full of Ghosts, Stephen Graham Jones’ My Heart is a Chainsaw, and Grady Hendrix’s How to Sell a Haunted House, fiction that displays how well the tools of horror can shed light on issues of trauma.

As an academic, do you tend to particularly enjoy sci-fi that engages with your area of expertise, or does most of it do so so poorly that you avoid it unless it comes highly recommended?

What I love are authors who, steeped in ideas that excite them, tell stories that can’t help but reflect those ideas—but who are clearly aiming to tell a good story and tell it well. I shy away from works where it looks as if the author has set out to make a profound philosophical point.

Maybe part of the reason is that, too often, those who try to do the latter have failed to take into account the range of objections—not to mention powerful arguments for alternative perspectives—that, as a philosopher, I have studied. But I think the main reason is this: In fiction, I think the story must come first. If an author tells a great story and, in the course of doing so, bungles the effort to make a deep philosophical point, I’ll forgive them. But if the effort to make a philosophical point drowns out the story, I won’t.

In writing So Eden Sank to Grief, my first hope was to tell a good story about characters the readers would care about. I hope I pulled that off. The rest is gravy.

As I said, I’m grateful to Eric for writing this novel and agreeing to answer questions about it. I found it an enjoyable, engaging, and thought-provoking read without knowing all this backstory to it, and I appreciate it even more in light of what Eric shared. When you read it, please come back and let me (and Eric) know what you thought of it. Ask your local public library to get it, just as I hope you do with my books. 😉

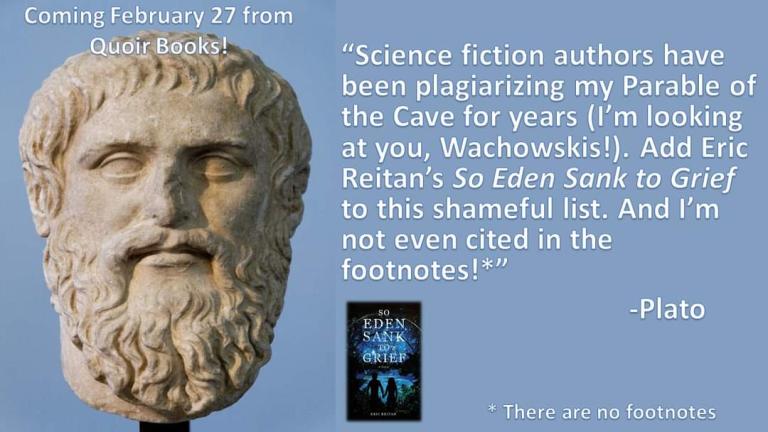

For more, check out Eric’s blog which includes endorsements of the novel by long-dead famous philosophers, an excerpt, and a reflection on philosophy, fiction, and the human condition. Here’s one of those aforementioned endorsements: