My colleague Brent Hege shared on Facebook the sense of trepidation one has as a professor who is not an expert in Shintoism, and finds that one has a student who is Shinto in a course that will include a brief overview of that tradition. I chimed in in a comment and wrote the following:

I had a baptism by fire of this sort when I first started at Butler. A Chinese speaker in my first time teaching what was completely new content to me and a real stretch out side of my field, a Change & Tradition core curriculum course on China and the Islamic Middle East. I then proceeded to have a Muslim in that course, and when I switched to the South Asian Civilization course, I had a Hindu student in it. It does great things for one’s humility!

A colleague then asked why it should make us nervous, since we regularly have Christian students in our classes and it doesn’t cause the same sort of worry. Here’s what I wrote in response:

In the case of Christianity or the Bible, Brent and I have knowledge of the lived tradition, plus the things that you learn in an academic setting going into greater detail. I imagine that Brent may well have done more, but my own academic studies didn’t include anything in-depth on Confucianism, Taoism, Islam, Hinduism, or Buddhism, and so when I’ve taught courses that include a substantial component about those traditions, I may have been able to draw on some useful groundwork related to how academics approach religion, but I have been largely self-taught and that self-teaching occurred when I prepared to teach the courses in question. And I have only learned Mandarin, Arabic, or Hindi at an extremely basic level. And so concerns about pronunciation, concerns that a student’s lived experience of the religion might include things that I’m unfamiliar with as a result of reading about the tradition, and concerns that students might bring up texts, rituals, or other things that my reading omitted, were all in my mind when teaching in these areas.

Now, the thing I should add is that I LOVED teaching these core courses and found the opportunity to put lifelong learning into practice in this way personally rewarding. Anything worth doing should be nerve-wracking at some point, especially when we reach the stage where we, as relative beginners, are going to put our meager talents on display before an audience which, at least in our imagination, may include those who are more talented or well-versed than ourselves. But of course, those who have studied anything at all will have passed through the level that you are currently at, and are unlikely to view your efforts with disdain. And so doing this in the classroom is particularly disconcerting, because there students have an expectation that the person who stands up at the front and speaks is an expert. And at Butler, whether in core curriculum courses or in religion classes that span a range of traditions, no one person is going to be equally an expert about everything that is covered. And so we get to illustrate not only expertise, but lifelong learning, to students, and I think there is something great about that.

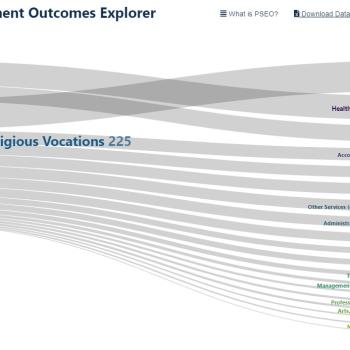

I think that students benefit not just when they see the fruit of professors’ lifelong learning, but are given a glimpse into the process as well. And so let me conclude this post with a link to an article my college dean circulated about a university president who decided to take a class. I’ve long thought that we ought to do more to foster an institutional culture at universities, which goes beyond merely making the possibility of taking classes available to faculty and staff, to actively encouraging and rewarding doing so. That would increase the ways in which faculty could model the practice of lifelong learning to students. We do it when we prepare classes, but it might give them a different perspective if they were to see us taking classes as well.