There are a lot of people in our time who can be described as “struggling with homosexuality.” In some cases, it is individuals struggling with their own sexuality. But in far more cases, it seems there are people who are heterosexuals and who are nonetheless ‘struggling with homosexuality’ – struggling to read the Bible in ways that are not harmful to other human beings, and struggling with their own innate tendency to disdain, judge, and interfere with the sexuality of others. And so I thought I would share here a brief summary of some key points that I and others have made on this blog and elsewhere. I wrote what follows in a Facebook message, in response to a question someone asked me on this topic, and I thought that perhaps it would be relevant to a larger audience.

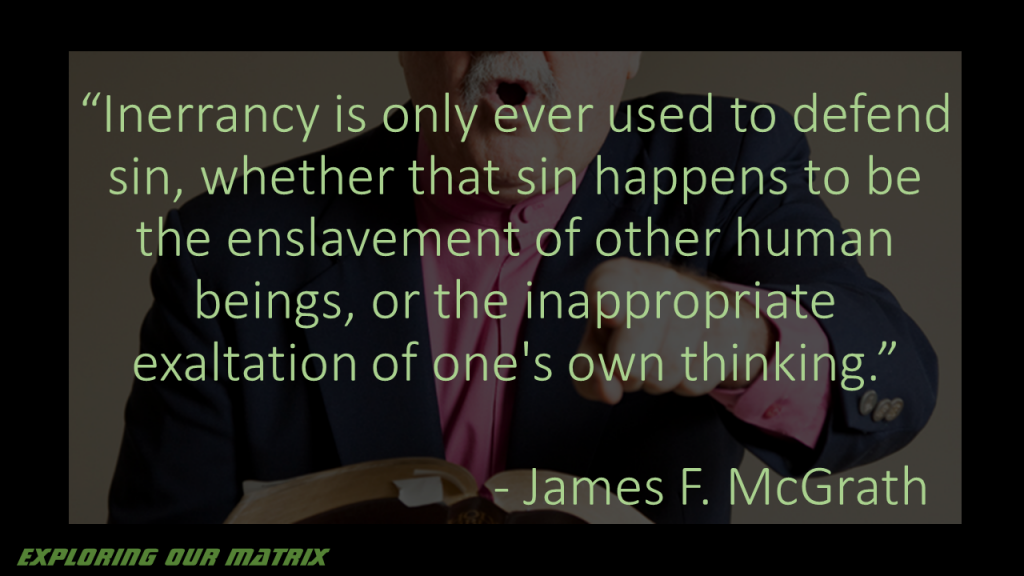

I think one has to begin with the question of how to approach the Bible if that is the source of a person’s concern about this. My own Baptist tradition has divided in the past over issues such as slavery and women in ministry, and the two camps have had underlying disagreements about how to approach the Bible. The conservative inerrantists made the claim that if one says that slavery is wrong, then the Torah was wrong to legislate but accept slavery, and Paul was wrong to council slaves to obey their masters without telling slaveowners to free their slaves. With hindsight, I hope you can see that inerrancy is used by the powerful to maintain structural evils, and is thus not an approach to the Bible that ought to be accepted by Christians. The alternative approach is to recognize that there are fundamental principles which individual Biblical authors did not always live up to. “Love your enemies” is not universally the outlook of the Bible’s authors, and an inerrantist in Jesus’ time could have rejected his teaching, making the same claim about hate that the Southern Baptists and others later did about slavery, saying that regarding hatred towards enemies as evil would make various Psalmists wrong and thus undermine the authority of Scripture.

In the case of human sexuality, the underlying principles in the Bible seem to be that it is not good for human beings to be alone. There is also a principle of fidelity, but it was not practiced in a gender-equal way in antiquity. A man only committed adultery if he slept with another man’s wife, but was not prohibitted from having more than one wife or concubine. The same was not true for women. And so it seems very odd to me that anyone could ever appeal to “Biblical marriage” in discussions of this topic, since marriage as practiced historically in the United States (outisde of Utah, obviously) is a very different institution from marriage in the Bible.

Finally, when it comes to the application of these principles and others, the most fundamental for a follower of Jesus is to treat others as we would wish to be treated. I think that this is still an issue for so many precisely because they have never genuinely reversed the situations. How would you react and respond if someone told you that heterosexuality is inherently evil? If they said that it is OK to have heterosexual desires as long as you never act on them, even in the context of marriage, and if they had in fact long made any marriage you might thus participate in illegal? If they said that it is inherently evil for you to feel love towards a person that you are attracted to simply because they are of the opposite gender from you, and that – despite the principle in Genesis 2 – it is not only good but required that you be alone, or otherwise enter into a marriage with someone of a gender to which you feel no attraction? Once you put yourself in the shoes of another, only then can you ask what the loving thing to do is, and how Christian principles apply.

But at the end of the day, it reflects the underlying issue of power that came up earlier when heterosexual men have this conversation, thinking that we ought to be the ones to judge another’s servant, and decide whether the feelings others have and the choices that others make are acceptable to God, even though they can clearly justify them with arguments based on the Bible – whether or not we find them persuasive. The slaveowners were often not best poised to evaluate the matter of abolition fairly, and men in positions of power were likewise not always open to reconsidering the questions related to women in leadership.

If you are still struggling with your own sinful tendencies – wheth to fail to empathize, to judge others, or to use things like biblical inerrancy to defend institutional evils as others have done in the past – I suppose the appropriate thing to say in conclusion is that you are loved despite these sins, and that you are invited to repent and to join together with Christians who are seeking – even though we fail often – to follow Jesus, including in his approach to Scripture, which was diametrically opposed to inerrantism, and instead touched the unclean and healed the historic enemy, and gave both a place at the table literally and metaphorically.