Yesterday I shared some things that came up in my Sunday school class, and since there has been a lot more written on this topic on blogs that I read, I want to share links to and excerpts from those other posts.

So, what’s the big picture of Jesus’ ethical vision?

- Followers of Jesus serve rather than dominate (Mark 10:42-45).

- Followers of Jesus forgive rather than retaliate (Matt 5:43-45; Col 3:13)

- Followers of Jesus suffer harm rather than inflict it (1 Pet 2:21; Mark 8:34-35).

- Followers of Jesus Repay Evil with Good rather than More Evil (Luke 6:27-28; Rom 12:14, 17-21).

- Followers of Jesus love rather than hate: “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35).

How, then, do the so-called violent actions of Jesus — his use of whip in the temple courts, his far from clear statement about taking up a sword, and even his strong words for the Pharisees in Matt 23 — fit into this pattern of ethics? If you choose one you have chosen on the basis of which you prefer. If you mesh them, the preponderance of the former outweighs by far the latter.

Randal Rauser emphasized the importance to begin with our conscience when reading the Bible:

The Bible includes some descriptions of divine action which are fundamentally at odds with the moral perceptions of properly functioning human beings. In some cases, God is presented as performing actions that appear to be wicked. In other cases, he is presented as commanding humans to perform actions that appear to be wicked. Of the latter, the single most disturbing passage is arguably found in 1 Samuel 15:3 in which God commands Saul to kill all the Amalekite people as well as their domesticated animals…The moral offense of this passage should be obvious to everyone. But if it isn’t, consider how you would react upon reading those directives in the Qur’an or any other extra-biblical source. In all those cases, the Christian’s moral indictment of the directive would be immediate and unqualified. Thus, at the very least, the Christian must concede that 1 Samuel 15:3 appears to present God as commanding wicked actions.

This leaves the Christian with two basic options.

Option 1: deny that the action in question is necessarily wicked.

Option 2: deny that God ever commanded the action in question.

..no Christian should believe Christian discipleship requires them to deny the most fundamental dictates of their own conscience.

See also his post about a recent book trying to make sense of genocidal texts in the Bible, in which he writes:

Likening a particular ethnic or religious or cultural group to cancer? It’s a horrifying analogue, particularly as it calls to mind countless other instances of dehumanizing genocidal rhetoric from the Nazis labeling of Jews as cockroaches to the Hutus calling Tutsis cockroaches. You can talk all you like about the herem of sinful impulses as you follow Christ, but that doesn’t change the fact that the text on which those spiritualized appropriations are based dehumanizes an entire population.

The example that I turned to, in my Sunday school class, since we had been talking about welcoming immigrants, was to set Nehemiah 13 alongside the laws about treating the foreigner in our midst as we would treat one of our own. But as the above shows, examples can be found in abundance.

Richard Beck wrote about this issue of the conscience and the Bible for Protestants. Here is an excerpt:

In short, in 1521 the monopoly on truth was busted up. The individual conscience–your conscience–was now able to decide and declare truth for itself. And while this has been a very good thing in many ways, it also comes with some consequences. Specifically, Protestants live with a perpetual crisis of authority. Yes, we have a Bible, but there is no way to adjudicate between two Protestants when they disagree about the Bible.

There is a paradox at the heart of many attempts to articulate a Christian systematic theology, and I’m thinking of making it a focus when I write a book (hopefully in the near future) about progressive Christianity as a natural expression of Christianity and as something that emerges naturally from the Bible. Theologically, the focus should be God, and then Jesus, in a Christian systematic theology. And yet how do we start with God? Systematic theologies may have “God” as their first chapter, but then they immediately start citing scripture, even though the doctrine of scripture is left for a later chapter. Even within frameworks that leave God as mysterious and turn first to Jesus, the historical figure of Jesus is not accessible to us without once again turning to our written sources. And so the Bible inevitably ends up inserted prematurely into the process of theological reflection, in ways that can easily lead to bibliolatry.

Keith Giles recently summed up nicely the motivation behind the attempt at biblicism:

The Bible is not a perfect book. It was not written by God, it was written by men, many of whom did not share the same perspectives about who God was and what God was like.

For Evangelical Protestants in America, this fact is very uncomfortable. Most Jewish scholars freely admit that their Hebrew Bible is a collection of varied opinions and perspectives on God and His nature. They are comfortable with the dialog, and the mystery, that these varied voices bring to the table for us to consider.

American Christians are most certainly NOT comfortable with mystery. We don’t want mystery, we want facts. We demand answers. We insist upon having the most exact and accurate information about God possible. Everything is either Black or White, when it comes to God and the Bible. There is no room for any shade of gray.

But as Rachel Held Evans emphasizes in her new book, Inspired, “The gospel is like a mosaic of stories, each one part of a larger story, yet beautiful and truthful on its own. There’s no formula, no blueprint.” See the helpful longer excerpt on her blog, in which she writes:

This is the deleterious snare of fundamentalism: It claims that the heart is so corrupted by sin, it simply cannot be trusted to sort right from wrong, good from evil, divine from depraved. Instinct, intuition, conscience, critical thinking—these impulses must be set aside whenever they appear to contradict the biblical text, because the good Christian never questions the “clear teachings of Scripture”; the good Christian listens to God, not her gut.

I’ve watched people get so entangled in this snare they contort into shapes unrecognizable. When you can’t trust your own God- given conscience to tell you what’s right, or your own God-given mind to tell you what’s true, you lose the capacity to engage the world in any meaningful, authentic way, and you become an easy target for authoritarian movements eager to exploit that vacuity for their gain. I tried reading Scripture with my conscience and curiosity suspended, and I felt, quite literally, disintegrated. I felt fractured and fake.

There’s another briefer excerpt on the Internet Monk blog, also related to this theme. I’m eagerly looking forward to reading the whole book!

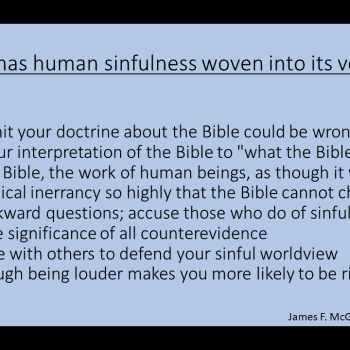

For those who’ve been raised indoctrinated by biblicism, it can feel sinful to acknowledge that the Bible can be wrong. But the truth is that elevating these human writings to a level of perfection and infallibility that humans do not have is what is sinful – from the perspective of the Bible’s own teachings, no less!

See too Sabio Lantz’s introduction to the Bible for non-believers in which he writes:

Religion is complicated. Christianity and Islam will tell you that correct belief is central to true religion. But the most important thing to know about a religion is not it’s beliefs (though you will need those), but how those beliefs are used by its believers.

Most Westerners, exposed culturally to Christianity, even if nonbelievers, are subconsciously hypnotized by this idea that a religion is its beliefs. Most folks feel they will understand a religion if they just read a list of their beliefs and maybe some of their history. But religions use their beliefs like tools to pursue social and personal goals. Mind you, believers themselves may tell you that it is all about correct beliefs, but they are wrong…