From the recent article by Dr. Gregg Gardner on biblical gleaning laws and the subsequent interpretation of them in rabbinic tradition:

Although the agricultural allocations to the poor share some characteristics with charity, they function differently. Charity is a positive duty whose underlying premise is that it comes from one’s own personal property and the benefactor exercises some discretion over what is given and how. Thus, in their discussion of charity, the rabbis do not specify the time or place for when it should be given. The biblical laws of harvest allocations, in contrast, have traits that are typically characterized as acts of justice.

While charity is defined by personal discretion, justice is devoid of it. Whereas the laws of charity do not allow for the recipients to claim that they are owed anything in particular, systems of justice provide the recipients with correlative rights. Since the agricultural allocation laws do have specific requirements about what the householder must do (the six items listed above) and to whom (the poor that show up to take these items), they are better characterized as acts of justice and not charity.

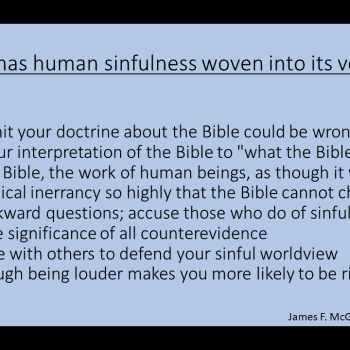

I’ve blogged here before about the fact that what we see in the relevant biblical texts is wealth redistribution through something that is in essence a form of tax. It is profoundly ironic that some claim to be concerned with “biblical morality” and yet rail against taxation, redistribution of wealth, social justice, systemic solutions to address poverty, and other things that are woven into the fabric of the Bible.

Yet on the other hand, as Gardner points out in his article, the gleaning law focuses on procedure and not on whether the needs of the poor are actually met, with the result that more truly redistributive laws and policies that are post-biblical do a better job of addressing these social issues. From his conclusion:

Both in the biblical text and their later interpretations by the rabbis, the laws of harvest-time allocations center on the principle that humans neither own the land nor its produce outright. Rather, a portion of the harvest belongs to God, which in turn God allocates to the poor, who are under God’s special care. Only upon ensuring that God and the poor receive their share can the landowner claim the rest of the harvest for himself.

As such, these laws focus primarily on the procedures that the landowner must follow so that these allocations are carried out properly. The rabbis would up the ante by ascribing a set of correlative rights to the poor, ensuring that there are human agents to whom these elements of the harvest are owed. That is, the focus of these laws is primarily on proper procedure – more so than the outcome of that procedure.

That said, the biblical text establishes the primacy and importance of care for the poor, and it is perhaps from this general ethos (though not derived from any particular text) that we see the development of a parallel form of support for the poor in post-biblical Jewish texts – namely, charity. It is in the post-biblical concept of charity, especially as it is fleshed out by the rabbis, that becomes increasingly focused on outcomes – i.e., on satisfying the specific needs of the poor.

On the same topic, Christy Thomas offered this challenge:

“Bible-believing Christians:” either wholeheartedly support a socialist governmental structure or acknowledge that you are liars. At this point, I think most are just liars.