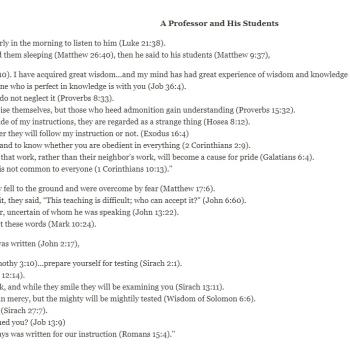

Peter Leithart’s post about the story of David and Goliath provides a helpful illustration of just how much the reader can contribute not merely to “finding meaning” in a text, but making meaning creatively in the act of reading. In a post called “The Bible and Information” he writes:

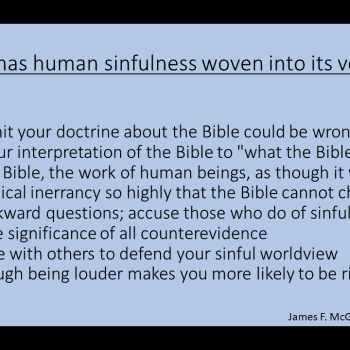

What Esther Meeks calls the “defective epistemic default” of modernity infects and paralyzes biblical interpretation. In this default, knowledge is defined as information.

This can only produce puzzlement about the details of the Bible. They aren’t symbols; they aren’t clues; they text isn’t pregnant with meaning. The details are there as mere bits of information.

Why, for instance, are we told that Goliath had a bronze helmet and scale armor and bronze greaves on his legs? Why are we told his height? Why do we need to know the weight of his armor and of the head of his spear? Why does it matter that David struck Goliath’s head with a stone?

A certain kind of commentator will say: Well, because Goliath actually wore armor and his spear’s head actually weighed that amount and David actually did sling a stone.

Try to move beyond, try to suss out the symbolic significance of these details, try to move beyond information to see the details as clues to a pattern, and you can expect to hear cries of “Allegorist! Origenist!”

But each of these details is significant.

When the spies came back from the land, they frightened Israel by saying that the land was filled with giants. Only Joshua and Caleb were giant-killers. David is a latter-day Joshua, ready to rid the land of giants, ready to rule in a way that Saul, the Israelite giant, cannot.

Goliath is dressed in scale armor; he’s dressed like a serpent. And, like the serpent he suffers a massive head wound from the seed of a woman.

He’s dressed in metal, and like the great metallic statue in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, he’s felled by a stone.

When we recognize the pregnancy of the text, this episode becomes a moment in the unveiling of Jesus Christ, who is the focal point of all Scripture.

I think that it is crucial to distinguish between different ways of approaching literature, and to recognize the vitality, positive contribution, and limitations of each. A book that I am long overdue to blog about is Roy Harrisville’s Pandora’s Box Opened: An Examination and Defense of Historical-Critical Method and Its Master Practitioners. It offers a fantastic exploration of many details in the history of Biblical scholarship, and places its methods and practices in direct dialogue with the work of philosophers and others whose perspectives are crucial to the critical evaluation of this approach to critical evaluation. Ultimately, as the title hints from the outset, our inability to attain objectivity or find bare uninterpreted historical facts does not allow us to entirely set aside the investigation of the past. He makes the case not only on the basis of philosophy and academic argument, but on the basis of Christian faith, which Harrisville says cannot abandon its responsibility to communicate with others and in the process to offer a reasoned, evidence-supported case for its beliefs.

Chris Glaser’s thoughts are also germane to this topic:

Context is needed to understand any biblical text, but not just its location in the Bible. The writer’s social location must be taken into account, certainly, but interpreting the Bible requires more. It is best understood within a tradition, not just the tradition that preceded it, not just the tradition of its time, but the tradition of how it was interpreted since and even how it might be interpreted in the future.

The same can be said of the biblical text itself, and the methods used by those who study it.

See too the thoughts from Weekend Fisher about whether information is the point of the Bible.