On Facebook, Laura Robinson shared a blog post by Alisa Childers from the Gospel Coalition website that offered yet another of its characteristic attacks on more mainstream forms of Christianity. In this one, they focus on what they perceive as similar points made by atheists and progressive Christians (not noticing that we made them first and the atheists borrowed them from us). Here is what Robinson wrote in her critique of the piece by Childers:

Okay, I want to talk about this article because I think this article wants to talk about me. The idea is that “progressive” Christians have dangerous beliefs that make them pretty similar to atheists, and need to be reigned in before their progressive Christianity develops into atheism, much in the way that HIV develops into AIDS, apparently.

According to the article, “progressive” or doubting Christians might have the problematic beliefs that the Bible assumes the existence of slavery and polygamy and is written by people. They might struggle with how a loving God could allow so much evil to happen in the world unchecked. Finally, they might have a culturally adaptable ethic.

I’m going to leave aside the fact that it would be hard to think of a religious group with more flexible and relative ethics than American evangelical Christians. (In 2011, 30 percent of evangelicals said an immoral person could still be a successful political leader. That number rose to 72 percent when Trump arrived. Being ethically relative isn’t a trait of progressive Christians, it’s a defining trait of evangelicals.) I’m particularly interested in the first two “problems” with progressive Christians — namely, questions about the Bible and questions about the problem of evil. The author says that the solution to the problematic beliefs of progressive Christians is to “provide a safe place for people to ask tough questions and process their doubts.”

My question is, where are you going to find a safe space to process your doubts in the presence of people who want you to learn to stop acknowledging self-evident true things about the Bible as part of your faith journey? The Bible DOES assume the existence of slavery and polygamy. It IS written by people. And there is no easy answer for why terrible things happen in the world. The work of being a Christian in the face of these things is learning how to be faithful in spite of these difficult truths — not writing off these truths as though acknowledging facts that are plainly in front of your face is a sign that you’ve gone rogue and needs to be brought to heel.

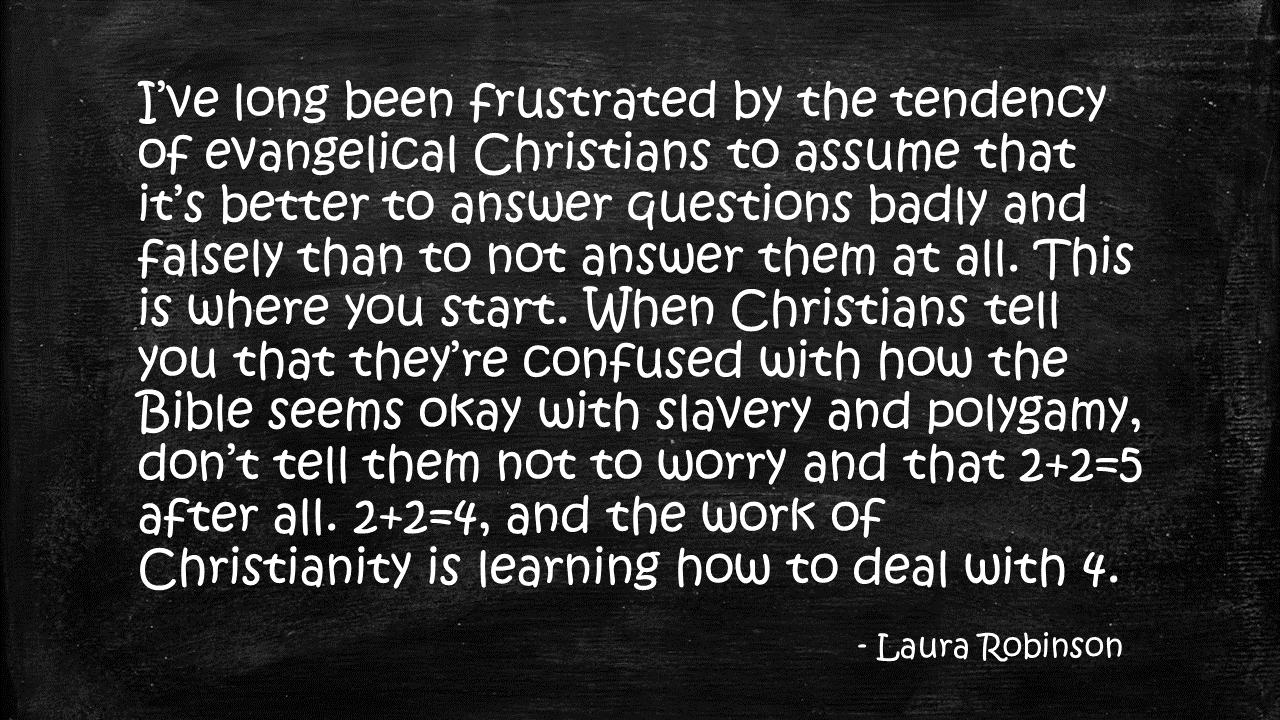

I’ve long been frustrated by the tendency of evangelical Christians to assume that it’s better to answer questions badly and falsely than to not answer them at all. This is where you start. When Christians tell you that they’re confused with how the Bible seems okay with slavery and polygamy, don’t tell them not to worry and that 2+2=5 after all. 2+2=4, and the work of Christianity is learning how to deal with 4.

I think you’ll agree that Robinson should start blogging and sharing her perspective with a wider audience. Robinson also adds in a comment:

The frustrating news for folks all over the Christian spectrum is that we have been handed down a canon that might be for us, but isn’t to us or from us. We’ve got a book that has its origins in a culture very unlike our own, and this takes a lot of wrestling and theological reflection to understand. So I don’t think an LGBTQ-affirming Christians has just cut those sections of the Bible out — I think they’ve done a lot of theological reflection and prayer on the way that marriage is portrayed in different canonical texts and have come to the conclusion that there’s room in Christina theology for two men to marry each other. Likewise, I don’t think that evangelical Christianity came to reject slavery and polygamy by editing out verses of Scripture that CLEARLY support both of those institutions, but by careful reflection on how the story of Jesus and the Gospel is incompatible with these ideas — even though they are permitted in Scripture. All Christians have to deal with the tensions and moral problems in scripture, and the difference between conservative and liberal Christians is that they come to different conclusions about how to do this.

I’ve addressed before the way conservative Christians attempt to preserve the same approach to scripture that was used to justify slavery, while at the same time trying to distance themselves from it. It doesn’t work – at least, not unless you assume what they need to prove, namely that that is the correct view, the only correct view, the one that God wants people to adopt. But they get there simply by assuming that their view is eternal truth, and not a backwards shift along a trajectory that had been aimed in a progressive direction.

On a similar note, Henry Neufeld posted on the inconsistency of many Christians’ hermeneutic across the spectrum. He writes,

I often use two texts from Leviticus in teaching about hermeneutics to lay audiences. The are:

- “You shall not lie with a male as with a woman. It is an abomination.” (Leviticus 18:22)

- “When an alien resides with you in your land, you shall not oppress the alien. The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you, you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the LORD your God.” (Leviticus 19:33-34, NRSV)

The results are often interesting with current American audiences. I’ve been using these two verses for years and I have seen no real change, other than differences based on the demographics of the audience I use it on. There will be people who are willing to accept both, but there are only a few of those. There are many who want Leviticus 18:22 to be applicable but not Leviticus 19:33-34, and those who want 19:33-34 to be applicable but not 18:22. Those who have thought through that application and provided a hermeneutic that can be consistently applied to texts are few and far between.