I enjoyed the television show Timeless immensely ever since it first started, and now that the show has concluded, I want to blog about it, as perhaps I should have done episode by episode all along.

The idea of temporal terrorism was just coming into view on Star Trek: Enterprise when it was cancelled, and other than the Spanish TV series that Timeless ripped off was inspired by, there hasn’t really been an exploration of precisely this scenario. And so that would have been enough to keep me interested. By “temporal terrorism” I mean things like eliminating individuals that oppose your ideology from the picture, in this case by killing them in the past or making it so that they never even existed in the first place.

All that is interesting enough. But when one episode brought God directly into the picture, that got me to sit up and take notice even more, as you might well have expected. Time travel and God intersect naturally, as I’ve discussed in connection with shows as diverse as Doctor Who and Fringe. But often the issue is whether time travel can take the place of God. Timeless, instead, focused on what place if any God has in a universe where time travel is possible.

The series was cancelled, but a two-part finale was aired recently to bring closure. Paul Levinson recently shared his thoughts about it, and that it its the sort of satisfying finale that makes one wish the show had continued. In an era when many people wait until a series wraps up and then binge watch it, I want to blog about why the show deserves your attention

Season 2 brought God into the picture more than others did, in a variety of interesting ways. As in any TV show, some of the references are superficial symbols and throwaway references. Others are profound. And as is usual, there is still more substance there when one is not looking merely for religious characters or iconography, but points of contact with what religion is and does. The organization that is working to change history in accordance with its white supremacist, patriarchal vision has a “cult manifesto” written by Nicholas Keynes, and it is described as being a mixture of The Handmaid’s Tale and Phillip K. Dick. There is talk by the team that is trying to stop them of preventing the apocalypse. When we meet Keynes as a character, he offers his vision of the future not only in speech and writing but painting. He says what he offers is not a map because they are not explorers, but rather artists with the mothership time machine as their brush. He describes them as carving away at the rock that is the human race until something like Michelangelo’s David emerges. The overall aim is described as “perfection everlasting.”

The third episode from season 2 is set against the backdrop of the Salem witch trials, and so engages with religion of that era in interesting ways. One of the activists opposing the witch hunts quotes the phrase “Beer is proof God wants us to be happy.” It turns out to be Abiah Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s mother, who finds herself accused of witchcraft. Another character says, “I haven’t touched a gun in years. I’m a godfearing man.” I particularly appreciated the direct and explicit reference to accusations of witchcraft being a form of terrorism to keep women from speaking their mind and having the influence they otherwise might.

Also interesting is the engagement with visions of the future, fate, and free will, in ways that lead naturally to the explicit discussion of God in episode 5. Jia and Rufus talk about a higher power, and the idea that everything happens for a reason. Rufus talks about his mother’s fruitless prayers to get them out of their crappy neighborhood, and states point blank that God does not exist. There is likewise discussion in another episode about the difference between prophecy and self-fulfilling prophecy.

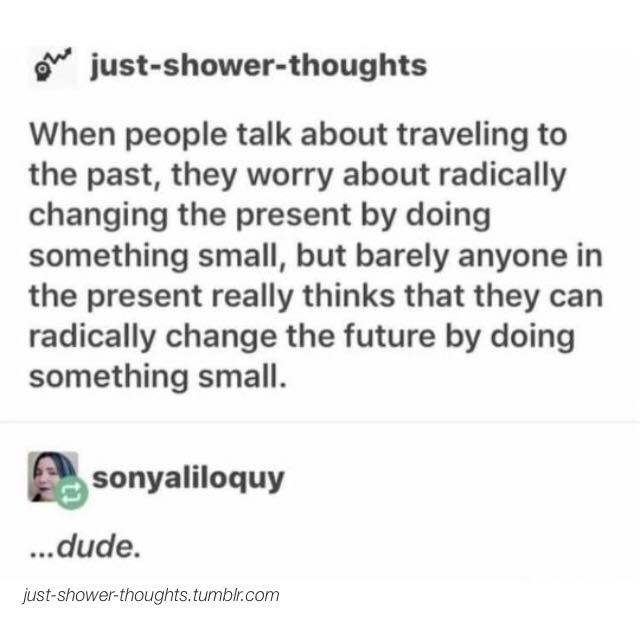

There are also great discussions of the impact of marching, protests, individual humans, speeches, and so on. Almost without fail, in their time such things seem to have minimal impact. It is only with hindsight that we see their significance. And so part of the show’s message is to challenge us to act as though our small efforts might reap greater rewards in the long term than we have any realistic justification to expect.

Time travel raises lots of question of morality, and not only in relation to the central question of whether it is appropriate to change history if one can do so. For instance, is it adultery if someone’s wife is dead, and one enters into another relationship, but then history is changed and the wife is now no longer dead?

The question of how time travel relates to God and miracles is interesting from another angle, since it would be easy to mistake the impact of time travelers manipulating history for divine activity, as Wyatt indicates when Lucy says that Wyatt getting Jessica back is the closest thing to a miracle that she has ever seen. See my discussion of a Fringe episode on that topic linked to above. See also Paul Levinson’s posts about the show’s episode about JFK, the relationship between Flynn and Lucy, time loops (particularly interesting in terms of how the series ended), and the season 2 finale.

The show ended with a two-hour finale that fittingly brings religious questions into the picture, albeit not in a manner that I felt was overbearing. In the episode, the team finds itself in North Korea towards the end of the Korean War, and at one point Lucy and Jia enter a church to keep warm. There a Christian who is not planning to evacuate talks to them. Her husband and son have fled but she hopes they will be reunited soon when, she hopes, the war will be over and things will go back to normal. Jia finds a pendant in the church of St. Christopher, the patron saint of travelers, which leads to a conversation about God between her and Rufus. When she had been stranded in Chinatown in the past, horrible things were done to her that led to her being literally as well as emotionally scarred. Yet it becomes clear that she has not lost her faith. She asks how she could possibly lose her faith in view of all the things that have happened, and so she believes that God will save them now. Meanwhile Rufus remarks that, if God were going to save anyone, you’d think that he (or she) would have saved the nun that had been killed.

Finally, let me mention the fact that Emma, a Writtenhouse agent who tried to take the organization over, asks at one point, “No hug? What would Jesus do?” Far from a mere throwaway quip, the remark illustrates the way the powerful use religion against the religious for malevolent ends. And yet it also stands as an invitation to watch a show like time travel and ask what Jesus would do…if he had a time machine.

I loved that the Korean woman who talks with Lucy was a history teacher and commented on the pressure on her to promulgate propaganda rather than teach history accurately – especially poignant in a show about time travel and changing history. I also loved that she quoted Marcus Garvey, and that Lucy much later explains to a student who complained that he thought this was a “regular history course” and yet she had focused entirely on women, that she had intended to get to the men but ran out of time. This is at a later point when Lucy is once again teaching history at university.

The show is all about the importance of the things and people that historically (pun intended) have been neglected – not just women and minorities, but family relationships and personal connections. Because, as the show says, “Everyone’s important to someone.” And those meaningful influences and connections make more of a difference than we realize without the benefit of hindsight.

Perhaps more than anything else this statement that has circulated on social media sums up a key point:

Have you watched Timeless? If not, now that it is finished, I hope you’ll take my recommendation and give it a try!