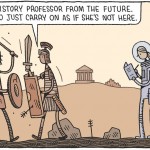

Having written about science fiction as prophecy here not long ago, I was struck by a recent article in the New York Times by Namwali Serpell. Here is one briefer and one longer excerpt:

Maybe because we’re living in a dystopia, it feels as if we’ve become obsessed with prophecy of late. Protest signs at the 2017 Women’s March read “Make Margaret Atwood Fiction Again!” and “Octavia Warned Us.” News headlines about abortion bans and the defunding of Planned Parenthood do seem ripped from the pages of Atwood’s novel “The Handmaid’s Tale” (1985). And Octavia Butler’s “Parable” series, published in the 1990s, did eerily feature a presidential candidate who vows to “make America great again.”

…

The writer Harry Turtledove tweeted a link to that article with an exclamatory comment: “Science fiction does not predict the future. Not. Not! [expletive] NOT! It uses the imagined future to comment on the real present.” Margaret Atwood often claims something similar, echoing Gibson’s protestations. Despite manifest evidence of her acute forecasts — the rise of the Christian right, in vitro meat, sexbots modeled on real people, apocalyptic climate change, live aquatic jewelry — she says: “I’m not a prophet. Honest, I’m not a prophet. If I were a prophet I would have cleaned up on the stock market years ago. … They’re saying things about ‘Oryx and Crake’ and ‘MaddAddam’ are all coming true. But that’s based on things people were already working on when I was writing the books. It’s just that I was looking for those things and other people weren’t.” Maybe science fiction’s future is actually just a lens on the present.

Some writers do like to don the mantle of prophet. In 1983, Isaac Asimov published a set of 2019 forecasts. He was right about some things: “The mobile computerized object, or robot, is already flooding into industry and will, in the course of the next generation, penetrate the home.” But it’s embarrassing to see how hopeful he was about us: Asimov thought computers would have freed us from the most tedious forms of labor by now. He imagined we’d have fixed pollution, developed technology “based on the special properties of space” and even settled on the moon. This rosy picture might seem surprising, given science fiction’s proclivity for doom and gloom. Yet given our headlong plummet toward the death of this planet, to picture any future at all feels optimistic these days. It assumes that, when the apocalypse comes, we will still be here to witness it.

Stories are one of our oldest technologies. They let us have vivid experiences — beautiful, moving ones, but also horrifying, dark ones — and then close the book, or the laptop, unscathed. They give us a kind of perverse pleasure in reverse: not of seeing the worst come true, but of seeing the worst without it coming true. And this is the other reason I don’t think writers should give up on the art of prediction. Writers don’t just see into the future or possess special insight into the present; we also construct a kind of machine for virtual hindsight. We create an immersive simulation of the future that we can all experience and look back on, so that we might decide together whether we want these dreams to come true after all.

I notice in particular how widespread the view is that prophets predict(ed) the future. What prophets past and present have done and do is precisely what Turtledove articulated: “It uses the imagined future to comment on the real present.”

Of course, it can be easy to miss this when reading the edited compilations of prophetic writings from our perspective, with the benefit of hindsight. For the most part, those things which simply didn’t come to pass have been left out, or altered. The classic example, mentioned regularly in treatments of redaction criticism, is Amos’ statement “I will destroy it from the face of the earth. Yet I will not totally destroy the descendants of Jacob” (Amos 9:8). The second part seems to many scholars to be an addition to the first part.

Another particularly clear example is to consider Omri, the king who is viewed by the Deuteronomistic History (see in particular 1 Kings 16:25) as the worst in Israel’s history. Look and see what the books named after prophets have to say about him. Basically, nothing. Why? Not only because our earliest prophetic books are later. But because Omri’s reign was a time of prosperity. Those who opposed him theologically may well have predicted doom and gloom. Nothing happened, at least not during his lifetime. The prophetic writings in the Bible are edited compilations of oracled and occasionally also stories. From the perspective of hindsight, we not only discern between individuals but between individual sayings. It would be interesting to be able to hear what these ancient Israelite prophets proclaimed and predicted that wasn’t recorded. But that would require yet another kind of science fictional technology.

To round off this post, here are a couple of links to posts of mine, more than ten years apart. Blogging probably has a chastening effect on anyone that might be inclined to predict the future. It is even easier to see how wrong someone can be not just about major events and trends, but even where a TV show like LOST is headed…

How Far We’ve Come: Things I’ve Learned from Star Trek