Eboo Patel wrote a while back:

The key argument for identity politics on the progressive side is redress of historical marginalization. In other words, because so many groups in American history were excluded because of their identity (blacks, women, gays, immigrants), it is high time that we create both cultural and policy solutions that tip the scales in their favor.

The key argument for identity politics on the conservative side is that religion shapes the lives and communities of traditionally-minded Christians in ways that ought to be protected by a nation that has a Constitutional guarantee of Freedom of Religion. It is noteworthy that significant numbers of traditionally-minded Muslims and Jews have found a home in conservative identity politics, although that has been complicated by the overt bigotry of Trump…

It makes no sense to say that race and gender are wonderful reasons to support certain candidates and policies for me, but religion is an illegitimate basis for identity politics for you. I don’t get to tell you what identities matter to you, or how to interpret those identities into political positions, especially if I am the one making the case that identities matter in politics.

Does this set up conflict? Absolutely it does. We shouldn’t be surprised when women, based on their gender, support pro-choice politics, and Christians, based on their religion, support pro-life politics. That is all entirely legitimate. And so are the women who say they are pro-life because they are women, and those who say they are pro-choice, because they are Christian.

This is the rough and tumble of living in a diverse democracy, that most remarkable form of human society where we are constantly faced with the differences we like, and the differences we don’t.

This connects quite directly with my work on algorithms and what we can learn about ethics in conversation with computer science. In recent months, Inside Higher Ed has featured numerous articles on navigating balance between freedom of speech and inclusivity, which are well worth reading and reflecting on if one is interested in this topic. It is good to see that there is increasing engagement with these matters in a way that doesn’t oversimplify things, and/or pretend that one can always preserve two values equally without ever having them come into conflict in a way that requires difficult decisions to be made.

Patel has been writing about these topics a lot, and while I don’t always agree with his stance or his recommendations (when he offers such), I consistently find his perspective insightful and helpfully provocative. Here is another more recent example:

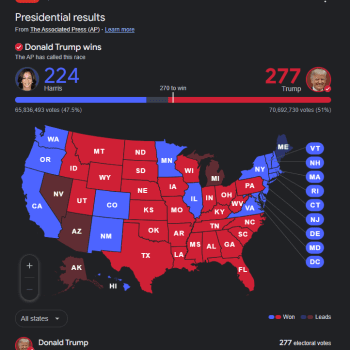

Carney presents study after study that shows that the places that lack basic community institutions are the same ones that exhibit high levels of human dysfunction and destruction – and the same ones that were all in for Trump early.

He also offers a creative theory on a fascinating question: why would places where the volunteer fire department no longer has volunteers grab on to a wrecking ball like Trump?

Because, Carney says, national elections are the most visible layer of our politics. Community institutions are the water that human beings swim in, and when they evaporate we’re like beached fish that don’t know what happened. We are so accustomed to patterns of community that it feels absolutely alien when they disappear.

Also, it’s slow, painstaking, unsexy work to relaunch the annual basketball tournament and set up practices for your team. Much easier to grab on to the rocket ship that flies by, blames people darker than you (yes, of course that’s racist and wrong) and promises to take you to the moon.

It’s interesting to think about the role of higher education in all of this.

There are a million wonderful things that college does, of course, but here’s one of the less wonderful things as it relates to geography: many colleges are set up to attract the most talented and driven young people from the Uniontown’s of the nation, educate them to sneer at the norms of where they’re from, encourage them to connect and mate with people who are similarly smart and driven, and then deposit them in cities where the knowledge-and-service economy is booming. It’s great for the cities, great for those individuals, great for the economy at a macro level, and terrible for their hometowns. The people who went off to college were likely the same ones who would run for mayor or volunteer to direct the school play.

(All of this makes me realize just how crucial a role regional colleges and universities play in the American landscape. We need more institutions that educate people who return to and enrich the places they are from rather than encouraging them to leave.)

A separate question: Should campus diversity progressives pay attention to geography in the way that we pay attention to race, gender and sexuality?

Just as we are – rightly – proactive about hiring people of color and women, should we be equally proactive about hiring people from towns where the economic base has eroded and the community institutions have disappeared?

See also Shadi Hamid’s recent article responding to Patel and reflecting on Muslims in American pluralism, as well as Sheila Kennedy on criticizing behavior versus hating an identity. Also important is the article that appeared in New Scientist about the social dimensions of radicalized hate. St. Eutychus blogged about whether voters for any given candidate feel welcome at your church. Inside Higher Ed explored identity politics on campus. Foreign Affairs looked at the connections between nationalism and the brains of primates.

See too the call for papers for a conference on religious identities and peacemaking in Europe, Keith Giles on healing our political divide, and Larry Hurtado on ethnicity and religious identities ancient and modern.

Also, Valerie Tarico on the psychology of outrage:

One Psychological Reason Democratic Primaries May Serve as a Trump Re-Election Campaign