As I’ve been doing in past summaries of this event, let me start with recent news and other such sources that relate to this topic. First, an article in the Christian Science Monitor recently made the point:

By its very nature liberal arts studies force students to dip into topics they’ve never thought about. Who might they become as adults? Their imaginations can be set free in unexpected ways, something that drilling down into a highly specialized STEM field too quickly may lack.

“You should pick a major you’re excited about, and you’re not going to know that for a couple of years,” former first lady Michelle Obama told a group of students who were the first in their families to attend college and wondering how to take advantage of the experience. “So just get out there and try some classes that make you feel excited, and pretty soon you’ll get a sense of which way to go. But take your time. There is no rush.”

There’s also a website, Humanities Indicators, that highlights the career trajectories and success of those who study humanities. See too the recent Chronicle article on getting students interested in the humanities, another about the need for the humanities to go on the offensive, and yet another about why hiring managers value students with a liberal arts education. There was also a piece on whether every student should learn computer science. How do you feel about the terminology of “soft skills”? IHE had pieces on gen ed reform and about Wichita State’s faculty senate. AAC&U explored liberal education in an interconnected world.

Now, continuing the recap of the day conference on the future of gen ed:

Don Laackman, president of Champlain College, discussed their professionally-focused educational mission. As a product of the University of Chicago core, he had been left to make connections among disciplines and with professional goals. Their approach was to get students to work on solving “wicked problems.” Some might describe the result as an “upside-down curriculum.” Their core runs in parallel with students’s majors. Everything comes together in their 4th year capstone which is co-taught by core faculty member and one in their major. Students develop a product, maintaining a process book in which students explain the cultural choices they made.

There was significant talk at the conference about Generation Z’s expectations. In response, there has been a shift towards having students co-create educational experiences, mentored by professional and core faculty.

Bradley Jackson of the Institute for Humane Studies at George Mason University said that diversity is the focus of key conversations happening on campuses today. How do we foster productive, empathetic conversations across difference? Colleges are well-poised to foster this crucial skill that is more necessary than ever in our world today, precisely because diversity is central to higher ed. Disciplinary diversity provides just one example. We need to explain to students why we have them engage with diverse fields, disciplines, and perspectives. Students will not remember content accurately in the long run, and some of what they learned will be invalidated. And so the crucial thing is to learn to embrace diversity itself and to navigate interactions across various kinds of diversity. Jackson studied physics, philosophy, and economics. Each thinks it is the queen of the sciences. Every science is the master discipline, every science is the queen, viewed from within its own domain. They provide different tools, not just procedures but ways of studying, and of perceiving value. Faculty really commit to one approach at many institutions, but the beautiful thing in gen ed is students not having to commit in this way. Ideological diversity is also at home in higher ed. No two department members agree. Any good question doesn’t only have two answers. There are as many answers as there are academics. Learning how to have civil constructive conversations with those they disagree with is something we should be well poised to mentor them in. (I would add that I’ve had experiences that would encourage me to expect this from faculty, and some that make me aware that some faculty struggle with this every bit as much as some students do).

George Mehaffy said he has no ideas any more, just concerns:

How we define gen ed: mostly clashing philosophies, no possible outcome, secret war over credit hours. What is necessary to be an educated person in the 21st century?

How we define gen ed: mostly clashing philosophies, no possible outcome, secret war over credit hours. What is necessary to be an educated person in the 21st century?- How we talk about it: we give a menu and encourage students to hurry through core. There is something a little bit tacky about people with jobs for life looking down at students wanting to get jobs.

- How we teach: our interests. Broccoli curriculum, good for you but not very appetizing.

- Failure to assess

- Connection to our democracy. Mehaffy notes the absence of this in most of what was said today. Particularly ironic given Gallup quote on wall.

If asked he would blow it up and start over, integrating active learning, problem solving, and communities, while eliminating disciplines. He would make the first year fundamentally different from everything else. And he made this statement that I think we all need to ponder long and hard: Institutions are perfectly designed for convenience and interests of faculty, not students.

Melinda Zook from Purdue offered her perspective from a context that has become increasingly STEM-focused. They were facing cancellation of classes right and left. Professional programs gobbled up majors from the liberal arts. They asked themselves: what if we have faculty rather than grad students teach intro courses? They designed liberal arts certificate called Cornerstone, with “Transformative Texts” 1 and 2 as components. A great statement she made was “Teach what you love and students will love what you teach.” In a “great books” course they work on written and oral communication. Faculty choose the texts. They offered 1000 seats, and ended up with 500 on the waitlist. They decided that next fall they would be offering 1800 seats. Students are now taught by a faculty member, a scholar, from the moment they come to campus. They can effectively mentor them, an adult they can talk to about pressures and pleasures of college life, study abroad, career pursuits, etc. Faculty get access to students they wouldn’t have otherwise taught, attracting minors and majors. The administration loves it.

Mark Schneider of Ursinus College said that connections are important to changing how students think about the world. We need to enable students to have important conversations. They present Four Open Questions: What should matter to me, how should we live together, how should we understand the world, and what should I do? These are not disciplinary questions. They get at them through linked courses plus a gen ed capstone. Students keep a 4-year journal in electronic format, reflecting on the 4 questions and what experiences on and off campus have changed them. These are important for students’ futures. Portfolios are connected with student applications for campus employment, to become RAs, etc. Commencement speakers address the 4 open questions.

See also:

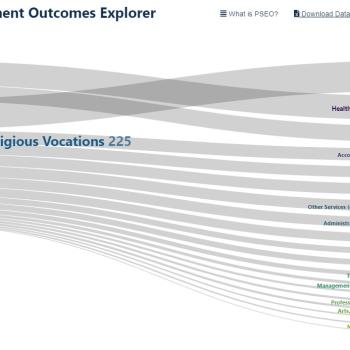

Return on investment for a college education

The need for the liberally educated in the military