The pandemic is going to permanently impact higher education. Some institutions are already closed. Funding for state universities has been reduced leading them to close departments and eliminate majors. Faculty who resisted teaching online were forced to do so. This post brings together a number of things related to this topic. There are discussions of the future of institutions and discussions of creative pedagogical responses to the pandemic that are happening separately when they ought to at least be in more conversation with one another than they currently are. I think one reason this hasn’t fully happened yet is that faculty are concerned about where this might lead. But if we let the conversation happen without us leading it, it is even more likely to lead in directions we are unhappy with.

Here is a roundup of some of the things that I’ve come across recently related to this topic:

There was a call for papers on teaching in times of change

Brand new books on the future of higher education are already obsolete

AJR had articles on Pandemic Pedagogy: Annotation as Close Reading and Pamphlet Final Projects (with laughter)

If you teach online again in the fall, don’t just do what you did this spring

Creating a Resilient Teaching Community

http://learningaloud.com/blog/2020/05/16/online-learning-vs-remote-instruction/

How the humanities can be part of the response to the pandemic

https://thewayofimprovement.com/2020/05/19/what-people-are-learning-about-themselves-and-others-during-this-pandemic/

How the coronavirus has shattered the myth of college in America

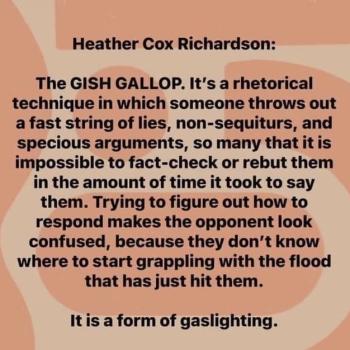

This response from Scott Ferguson to claims that edtech will provide solutions in the form of AI personalized education seems on target to me. Here’s an excerpt that is particularly important:

If one really wants to get the sort of data that can feed real individualization, then one must very strictly control the situation – control the variables and control the change, i.e. strip away all the complexity. And there are enormous problems in fully applying this. The obvious one is that it calls for a radical change in the student’s educational program (and with that one runs into toxic politics). But the more subtle and far more basic problem is that simplifying things so as to get “good data” also means losing any benefits one was getting from the complexity. Complexity and good data are inversely related, and a complicated setup works really well in more situations.

The trap here is to think that a messy, humanistic style of education where students all do a ton of different things, and do them together in a highly responsive social atmosphere, and converse and learn in a way where there’s a loose structure but where they must also find their own way in a common activity – play, for lack of a better word – just can’t work as well as a style where they’re fed individualized work with each element trackable and itemized. But just because we can’t “track” what’s happening doesn’t mean nothing’s happening – indeed, dabbling with lots of things can be hugely productive. And, as I suggested above, the “tracking” cannot come free: if there can be a data-driven individualization approach in human development that really works (such as Bondarchuk’s), it is only because it simplifies the situation so that it cannot fail to get the data that it needs. If you really want to individualize you must strip things down, cut off all the play and any benefits it was providing. Genuine individualization, then, is surely not worthless, but given the conditions it really becomes compelling only when a more complex setup ceases to be effective or useful. In education that’s normally cases of mid- to high-level specialization (grad school, say) or for students who, for whatever reason, do not respond well to the more traditional approaches. It might be a useful tool, but it shouldn’t be the first one we reach for: even if a student isn’t progressing “optimally” in a more complex setup (however we may gauge that), as long as they can indeed still make progress in many different fields at once then it may not be worth the cost.

Individualization is real, then, only within its limits. Any heirs of Knewton, insofar as they still make grand promises about educational paradise via magical robot tutors and no major policy changes, should thereby be designated vaporware until they prove otherwise: if we want meaningful improvements in education at any level at a large scale, we are left only with the hard reality of policy work. But if we get nothing else out of those billions of dollars lost, the lessons of control theory and Bondarchuk might teach us something about our own approach to teaching.

We are, in our modest way, in a better situation than the robot tutor which is only plugged into an educational system that it cannot otherwise change. We at least have control over our own classes if not the three other classes the students are taking, the internships, etc. (certainly not pandemics). “Individualization,” at bottom, means making the right change at the right time, that in turn only being effective when we have some sense of what’s going on. Normally it also means individuals and very exacting decision-making. But the term might be extended a bit. Even if our capacities for getting information and controlling change remain limited – even if we can’t individualize for students beyond the basics – we can still “individualize” within the limits of what we control. We can still apply some of the lessons to our classes.

As the Tech Edvocate writes, “AI will never take away the job of a teacher who is compassionate and curriculum-centered. These teachers build rapport and relationships with their students while coaching, mentoring, and cheering them toward their academic goals. They communicate on an emotional level with their students. That’s something AI cannot do.”

Higher education is being transformed by the Coronavirus

Quarantine campuses: With dorms shut and class online, students DIY college life

This post started out as being about the future of Christian higher education, as I started to round up the multiple blog posts on that topic that were shared at one point back in 2016. The conversation petered out then, however, and so it remained a draft post. However, there are specific challenges that will impact religiously affiliated schools that also deserve discussion. And so I decided to include those posts together with this broader treatment of the topic, and to add some more recent ones on that specific subject that emerged in the context of the pandemic.

http://eerdword.com/2020/05/05/promise-and-possibility-digital-life-together/

Iain Provan on Christian education

Why theological schools need tenure

Wheaton College, Larycia Hawkins, and our academic life together

A conference will be held in 2021 on the future of Christian thinking

Also related:

When the Real World turns Virtual…the new reality of office life?