There have been a lot of helpful resources shared lately that pertain to whiteness. I want to share a few here. But first let me mention my conviction that even terminology that is used in efforts to combat racism and work for inclusivity reflects a racist framework. The only way that one can talk about “people of color” is to treat whiteness as a lack of color, as the default in relation to which everything else is defined. How might we eliminate ways of talking about shades of skin pigmentation (as well as other characteristics of human appearance that historically tended to vary by region) without racism being woven into the very concepts and ways of speaking? How do we find ways of talking about skin pigmentation that are no different from the ways we talk about variations in hair and eye color?

Now for some of the helpful resources I’ve come across in recent days. First, Lyndsey Medford writes for Sojourners:

Of course, neither ennui nor self-deception is an invention of white people. But in the wealthy white suburbs we’ve inherited a culture of disconnection, a colonizing imagination, habits that live deep at the level of our being. Just like those McMansion dwellers who should, by all rights, be happy, my family has participated in the same project of whiteness for centuries.

In Forsyth, the forest is left unsaid. The Indigenous people who once tended this stolen land are left unsaid. Those who were driven out to create this all-white dystopia are left unsaid. The despair of the wealthy is left unsaid. The feeling that something is not right is left unsaid.

I’m still learning how to say that my ancestors were not simply “Revolutionaries” and “pioneers” but also colonizers who were instrumental in the theft of Black and Indigenous land, labor, and lives. I don’t know where to begin my own healing except to face those truths.

It’s not that being white is something to be ashamed of. I can’t help my pale, freckled skin, or the way others perceive me. I love my skin, dotted with auburn, and crisscrossed with faint blue lines. I love my family’s skin. I love my family. “Whiteness,” though, is not my skin or my family. Whiteness is the project of inventing systems and structures maintaining artificial hierarchies.

In order to participate in such a brutal project, my ancestors had to learn to perform the psychological gymnastics of declaring their victims subhuman. As that declaration was enshrined in law, religious practice, written history, social customs, science and medicine, and in human beings’ hearts, generation upon generation was raised with supremacy as the only reality they ever knew.

But no matter how much power and privilege you gain, you warp your heart and your children’s hearts in the process of abusing others. As a result, we are a people group who live lives of profound alienation from the connections — to others, to land, to Creator, to aspects of our selves, to creativity and Spirit — that make us most deeply, truly human.

When we contend that in relation to God, every human has a generic nature that can be reduced to innate, ahistorical total depravity from which the only salvation is a single, generic solution provided by Jesus, then we have an #AllLivesMatter theology. This is the teaching I received in white evangelicalism. I suspect it doesn’t seem controversial at all. It certainly didn’t feel that way when I was learning it. We simply operated under the assumption that every human on the planet is wired exactly the same way as a sinner, regardless of all the intricate cultural differences throughout the world that give things like pride and greed radically different meanings and manifestations in cultures that aren’t rooted in the acultural individualistic rationalism of the European Enlightenment. We presumed cultural difference to be as detachable from individual human experience as winter coats that can be taken off and left on a hook by the front door. I understand this may be difficult to get your head around, but what makes white Christian theology “white” is the claim that Christianity offers a generic, one-size-fits-all solution for everyone, regardless of whether they have an ancestral legacy of centuries of trauma from being slaughtered, beaten, and dehumanized or an ancestral legacy of centuries of guilt for having slaughtered, beaten, and dehumanized others. Whiteness is the presumption that human nature is fundamentally generic and then the resulting prejudice against humans who prove to be less than generic whether because their skin pigment is different than the default shade of pinkish beige or because their culture is louder, ruder, snobbier, or more emotional than the acultural rationalism of calm, confident white men…

It seems to me that these Christians who deny that there is systemic racism, power inequalities, etc., would like people to believe that if Jesus was here in the flesh, during this current time in history, he would gather the disciples in a room and hold a 24 hour prayer vigil, declare that sin was at the center of racism and all should pray for those afflicted, and then all go back to their homes continuing on as before.

The confusion for me comes from the fact that this is so contradictory to the Scriptural portrayal of Jesus, who was to say the least, a revolutionary and activist of his time. He knew that He was and possessed the power of God, yet he humbled himself and only used His power in order to serve and to advantage others who had no power. He openly and consistently contradicted and challenged the religious leaders of that time who used their power and position to oppress the poor, to abuse and take advantage of women and children, to exile and disenfranchise the sick and disabled, and to ignore and subordinate the foreigners among them.

Jesus’s behaviors and views on these topics can be seen throughout the Gospels. John 7:53-8:11 challenged the cultural practice of stoning women charged with adultery. Throughout the Gospels are stories of Jesus healing and touching those who were sick and diseased. The Gospels challenged the tradition of certain Jews holding themselves superior to others like that of the Samaritans. For instances, the Parable of the Good Samaritan found in Luke 10:25-37 is a call to help the ‘neighbor’ regardless of who they are. Another example is in John 4:4-30 with Jesus’s interaction with the Samaritan “woman at the well.”

Jesus challenged the status quo of the time, disrupting their traditions, regulations and those systems that had become corrupt and oppressive. His followers were considered outlaws, terrorists, firestarters by spreading a message of service, love, and reconciliation that turned the power structures of the day upside down. Galatians 3:28 states, “There is neither Jew nor Greek…” which allowed for ethnic and racial dividers to be torn down. All were invited to the table, what a revolution.

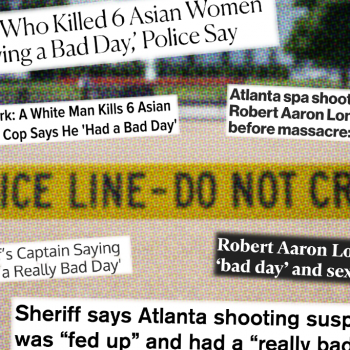

So here we are again, confronting the power structures that continually and historically oppress, subordinate and disenfranchise the poor, the foreigners, those who are racially and ethnically different. The criminal justice system that creates laws that encourage the unequal sentencing of drug use depending on which communities use what drugs. (i.e. sentencing for use of powder cocaine vs. crack cocaine). The disproportionate incarceration of black and brown young men. The criminal justice and law enforcement systems that allow unarmed black men and women to be killed, while refusing to prosecute those officers, regardless of the overwhelming evidence provided by videos and other witnesses capturing the killings. Why? The simple answer is to continue to hold the reins of power, wealth, and control.

If those of us who call ourselves Christians are willing to stand by, to discourage those who courageously and boldly, even loudly challenge these systems, how are we followers of Jesus? Rather it is those who follow the example of Jesus, who should passionately use whatever power, position and resources they have to dismantle those systems that are corrupt and oppressive, to come along side of the weakest and smallest of us and make sure we all have a seat at the best table in the house.

Some people resist the concept of “White privilege” because they think it means they should feel guilty for something they can’t control. That would indeed be wrong. Fortunately, that’s not what it means. Instead, “White privilege” simply means that being White bestows certain privileges in this culture, at the expense of other people. You didn’t create this system, but being its beneficiary bestows on you the moral responsibility to help dismantle it. This is all the more true for Christians, who are called to follow Jesus in laying down our lives in the service of others. I was aware of and sympathetic with the protests calling for change in the patterns that led to the murders of Black men and women at the hands of some police officers and neighborhood vigilantes. But the threat of COVID-19 affected me more directly and took up more of my mental energy than the threat to Black lives from violence. Realizing the parallel was what it took to break through to the next emotional layer of empathy for what African Americans have been experiencing: the constant effects of systemic sin…

Sometimes images help convey the point. There are a couple on the Showing Up for Racial Justice website. See also the political cartoon here. Also of possible interest: why African spirituality became associated with Satan.