After I shared Jana Riess’ great article about Kristin Swenson’s recent book A Most Peculiar Book: The Inherent Strangeness of the Bible, it became clear to me that I don’t always talk with my family or my Sunday school class about things that I now take for granted and that seem obvious to me, common knowledge about the Bible. Or if I have mentioned them, I may have done so once, in passing, and not provided an opportunity to explore them and reflect on them.

It was from Jeffrey Stackert at the University of Chicago, presenting at a Midwest Society of Biblical Literature meeting, that I got the idea that Exodus 7 could be particularly useful in helping students to grapple with some key aspects of not only source criticism but Bible reading more generally.

His class activity, apparently used on the first day, presents students with Exodus 7:14-25 which reads:

14 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Pharaoh’s heart is heavy; he refuses to let the people go. 15 Go to Pharaoh in the morning, as he is going out to the water; stand by at the river bank to meet him, and take in your hand the staff that was turned into a snake. 16 Say to him, ‘The Lord, the God of the Hebrews, sent me to you to say, “Let my people go, so that they may worship me in the wilderness.” But until now you have not listened. 17 Thus says the Lord, “By this you shall know that I am the Lord.” See, with the staff that is in my hand I will strike the water that is in the Nile, and it shall be turned to blood. 18 The fish in the river shall die, the river itself shall stink, and the Egyptians shall be unable to drink water from the Nile.’” 19 The Lord said to Moses, “Say to Aaron, ‘Take your staff and stretch out your hand over the waters of Egypt—over its rivers, its canals, and its ponds, and all its pools of water—so that they may become blood; and there shall be blood throughout the whole land of Egypt, even in (vessels of) wood and stone.’”

20 Moses and Aaron did just as the Lord commanded. In the sight of Pharaoh and of his officials he lifted up the staff and struck the water in the river, and all the water in the river was turned into blood, 21 and the fish in the river died. The river stank so that the Egyptians could not drink its water, and there was blood throughout the whole land of Egypt. 22 But the magicians of Egypt did the same by their magic; so Pharaoh’s heart became strong, and he would not listen to them, as the Lord had said. 23 Pharaoh turned and went into his house, and he did not set his mind on this again. 24 And all the Egyptians had to dig along the Nile for water to drink, for they could not drink the water of the Nile.

25 Seven days passed after the Lord had struck the Nile.

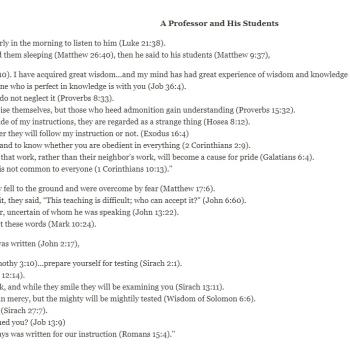

Students can be asked to break into small groups and try to answer questions that seem simple such as “Whose staff is it?”; “What do they do with the staff?”; and “What water is turned to blood?” One likely outcome is that students will be frustrated, reinforcing the assumption either that the Bible doesn’t make sense, or that they must be wicked and depraved individuals because this holy book does not make sense to them. Most students have only two go-to options: either the text is a contradictory mess because the text and its author are stupid, or the text seems a contradictory mess even though it isn’t because they as readers are stupid. A professor can use this opportunity to address these instinctive reactions. Present the students with this:

14 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Pharaoh’s heart is heavy; he refuses to let the people go. 15 Go to Pharaoh in the morning, as he is going out to the water; stand by at the river bank to meet him, and take in your hand the staff that was turned into a snake. 16 Say to him, ‘The Lord, the God of the Hebrews, sent me to you to say, “Let my people go, so that they may worship me in the wilderness.” But until now you have not listened. 17 Thus says the Lord, “By this you shall know that I am the Lord.” See, with the staff that is in my hand I will strike the water that is in the Nile, and it shall be turned to blood. 18 The fish in the river shall die, the river itself shall stink, and the Egyptians shall be unable to drink water from the Nile.’” 19 The Lord said to Moses, “Say to Aaron, ‘Take your staff and stretch out your hand over the waters of Egypt—over its rivers, its canals, and its ponds, and all its pools of water—so that they may become blood; and there shall be blood throughout the whole land of Egypt, even in (vessels of) wood and stone.’”

20 Moses and Aaron did just as the Lord commanded. In the sight of Pharaoh and of his officials he lifted up the staff and struck the water in the river, and all the water in the river was turned into blood, 21 and the fish in the river died. The river stank so that the Egyptians could not drink its water, and there was blood throughout the whole land of Egypt. 22 But the magicians of Egypt did the same by their magic; so Pharaoh’s heart became strong, and he would not listen to them, as the Lord had said. 23 Pharaoh turned and went into his house, and he did not set his mind on this again. 24 And all the Egyptians had to dig along the Nile for water to drink, for they could not drink the water of the Nile.

25 Seven days passed after the Lord had struck the Nile.

Use highlighting to make it even clearer, and better still, separate out the two:

J Source

14 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Pharaoh’s heart is heavy; he refuses to let the people go. 15 Go to Pharaoh in the morning, as he is going out to the water; stand by at the river bank to meet him, and take in your hand the staff that was turned into a snake. 16 Say to him, ‘The Lord, the God of the Hebrews, sent me to you to say, “Let my people go, so that they may worship me in the wilderness.” But until now you have not listened. 17 Thus says the Lord, “By this you shall know that I am the Lord.” See, with the staff that is in my hand I will strike the water that is in the Nile, and it shall be turned to blood. 18 The fish in the river shall die, the river itself shall stink, and the Egyptians shall be unable to drink water from the Nile.’” In the sight of Pharaoh and of his officials he lifted up the staff and struck the water in the river, and all the water in the river was turned into blood, 21 and the fish in the river died. The river stank so that the Egyptians could not drink its water, 23 Pharaoh turned and went into his house, and he did not set his mind on this again. 24 And all the Egyptians had to dig along the Nile for water to drink, for they could not drink the water of the Nile.

25 Seven days passed after the Lord had struck the Nile.

P source:

19 The Lord said to Moses, “Say to Aaron, ‘Take your staff and stretch out your hand over the waters of Egypt—over its rivers, its canals, and its ponds, and all its pools of water—so that they may become blood; and there shall be blood throughout the whole land of Egypt, even in (vessels of) wood and stone.’”

20 Moses and Aaron did just as the Lord commanded, and there was blood throughout the whole land of Egypt. 22 But the magicians of Egypt did the same by their magic; so Pharaoh’s heart became strong, and he would not listen to them, as the Lord had said.

Separated in this way we have two coherent narratives. Just as we can imagine someone combining the infancy stories of Matthew and Luke into a single Christmas pageant that lacks internal narrative coherence, and we might be able to trace behind that single story two separate sources each of which made sense but which create tensions when combined, so too the author of Genesis can be seen to have had more than one authoritative text to work with and woven them together.

In plenty of instances we may not be able to discern what sources precisely were involved. That doesn’t negate the broad principle that multiple sources can be detected at least in places, and thus some confusing elements can be explained as a result of their combination.

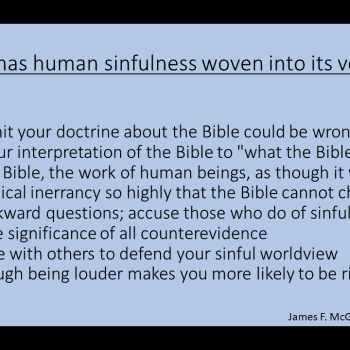

By introducing this through an inductive activity, you get a chance to reassure students that neither they nor the text is simply unworthy, and to help them appreciate source criticism not just as a solution to this specific problem but as one of many things scholars have done not in an effort to tear the Bible to pieces in a disrespectful manner, but to listen so closely and respectfully that we notice its contradictions and tensions and seek to find ways of making sense of them. Whether one ultimately accepts the Documentary Hypothesis, it isn’t an alien framework imposed on the Bible in order to discredit it or due to some inappropriate motives. It is an attempt to make sense of puzzling features and explain them.

Thanks to a recent article by Alan Levenson, this activity could also be used to dig into how scholars’ lives and ideologies relate to their scholarly work. The idea that there are sources behind the Pentateuch does not originate with Julius Wellhausen, but he played an influential role in systematizing and popularizing it in a way that has impacted scholarship down to the present day. Are his antisemitic assumptions relevant to his work and how we engage with it? The short answer is “absolutely.” Nevertheless, that doesn’t mean that one dismisses source criticism, any more than one dismisses certain developments in late Romantic and early modern musical tonality because of the role that Richard Wagner, also deeply antisemitic, played in the history of music. We can flag Wagner as who and what he was, and still mention him on our way to the still more revolutionary developments in (a)tonality that are associated with Arnold Schoenberg. There has been more than ample Jewish work on source criticism, and more than enough critical engagement with Wellhausen, that we needn’t either ignore him nor sweep his biases and their impact on his views under the carpet. He is but one source, and without him in the picture some other discussions of source criticism may seem puzzling.

Source criticism is of course just one of the many ways of approaching the Bible that can help to answer questions and make sense of puzzles. While in conservative Evangelical circles you might here that the Documentary Hypothesis is a defunct relic of the past, much as you might hear the same thing about Darwin and Evolution, the truth is that both source criticism and biology are so far advanced beyond Wellhausen and Darwin that there is no need to exaggerate their importance or hide their failings. Indeed, being honest about these things can help students wrestle with questions of authority, expertise, and bias, matters that they cannot sidestep either in the authors they read or in themselves.

Here is the link to Jana Riess’ article I mentioned at the beginning once more: